1915: The Year In Crosswords

The car, the letters, the diamonds, the...swastika?

Here continues my year-by-year documentation of crossword history. I need to pick up the pace on this if I’m going to catch up to modern times, so I’ll probably try another this time next week.

When researching early references to the crossword, one comes across a lot of false positives. The earliest “cross-words” in print had nothing to do with puzzles: cross-word, and occasionally crossword, used to be a condensed term for cross words, which is to say, words spoken in anger. Which, in turn, was sometimes a euphemism for cussin’. I can imagine a small number of readers in the 1910s hearing the term cross-word puzzle and expecting something more like Francis Heaney’s Crasswords.

A few so-called “cross-words” continued to appear that were actually acrostic challenges or word squares to be drawn out by the reader. The New York World’s FUN section continued to be the only source for crosswords anything like what we know today—although that Fun section was reprinted in other papers like The Minneapolis Journal, which added to its reach.

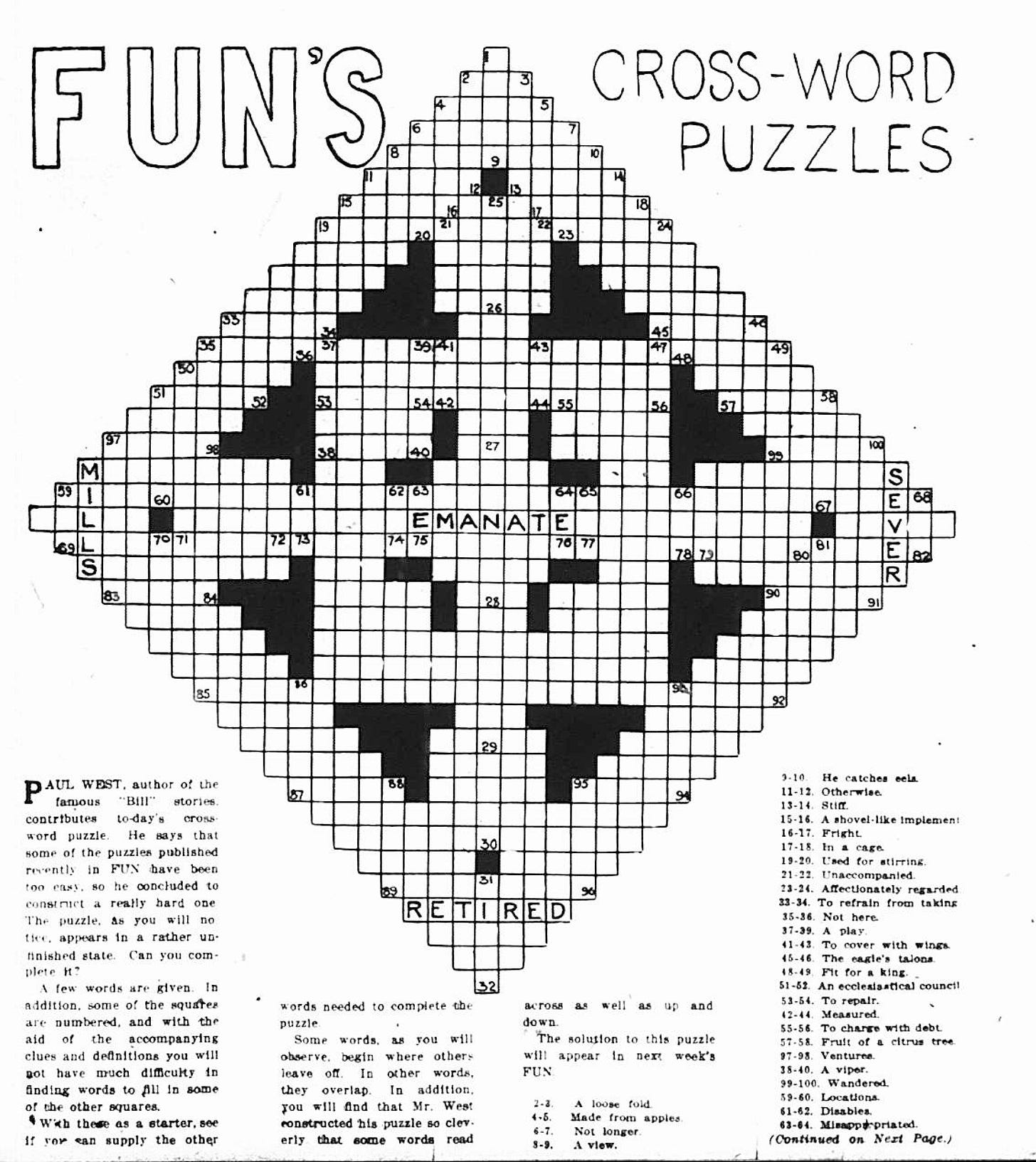

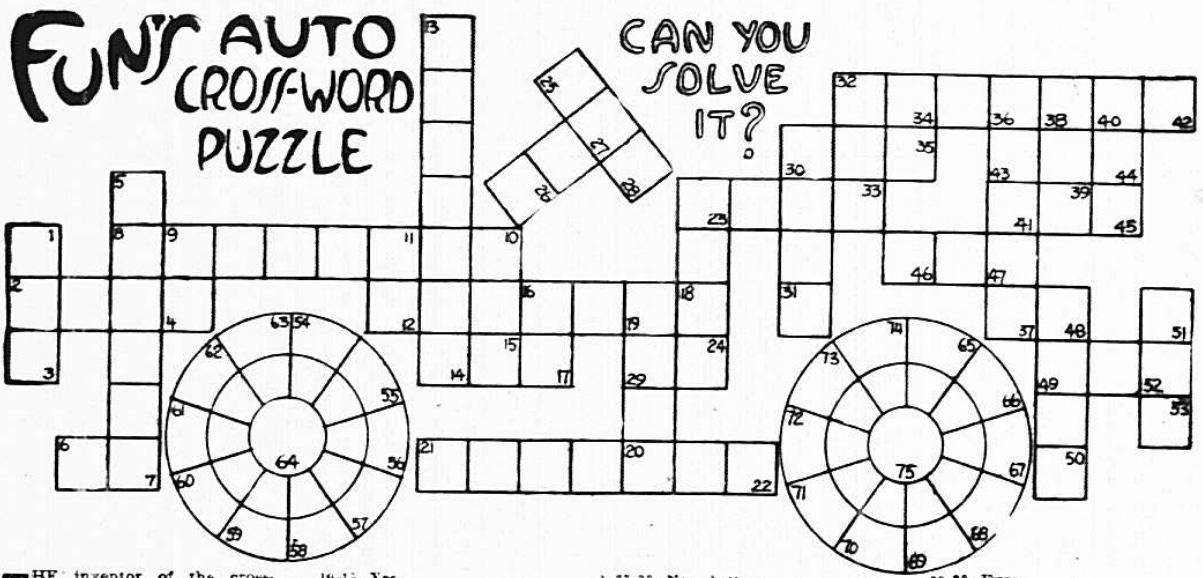

1915 was a year of continued innovation in grid design. Consider this not-so-little gem:

This grid did not behave like modern grids. Some areas contained multiple answers next to each other, and large sections of the puzzle had answers that only worked in one direction. The modern equivalent would be the barred crossword, which separates its white squares with heavy lines but may not include any fully black squares.

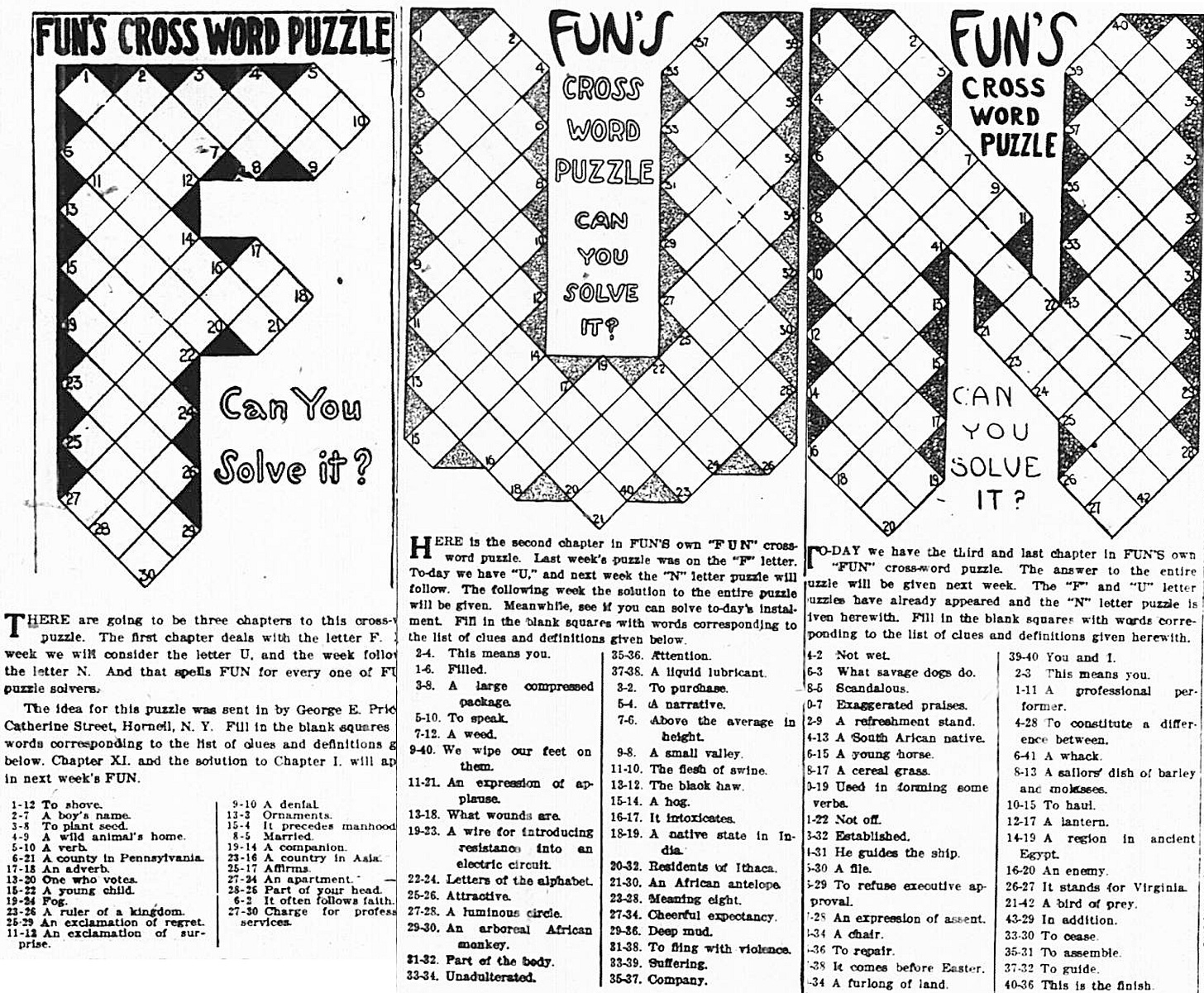

In January, Fun ran a series of three crosswords with diagonal, letter-shaped designs, the first an F, the next a U, the last an N. “That spells FUN for every one of FUN’s puzzle solvers,” as Arthur Wynne wrote.

On March 7, 1915, Wynne painted a picture for his readers of the FUN flood of submissions:

The editor of FUN receives an average of twenty-five cross-words every day from readers. Considering that only one cross-word is published per week, you can possibly imagine what the office of FUN is beginning to look like. Everywhere your eyes rest on boxes, barrels, and crates, each one filled with cross-word puzzles patiently awaiting publication.

However, the editor of FUN hopes to use them all in time. The puzzle editor has kindly figured out that the present supply will last until the second week in December, 2100.

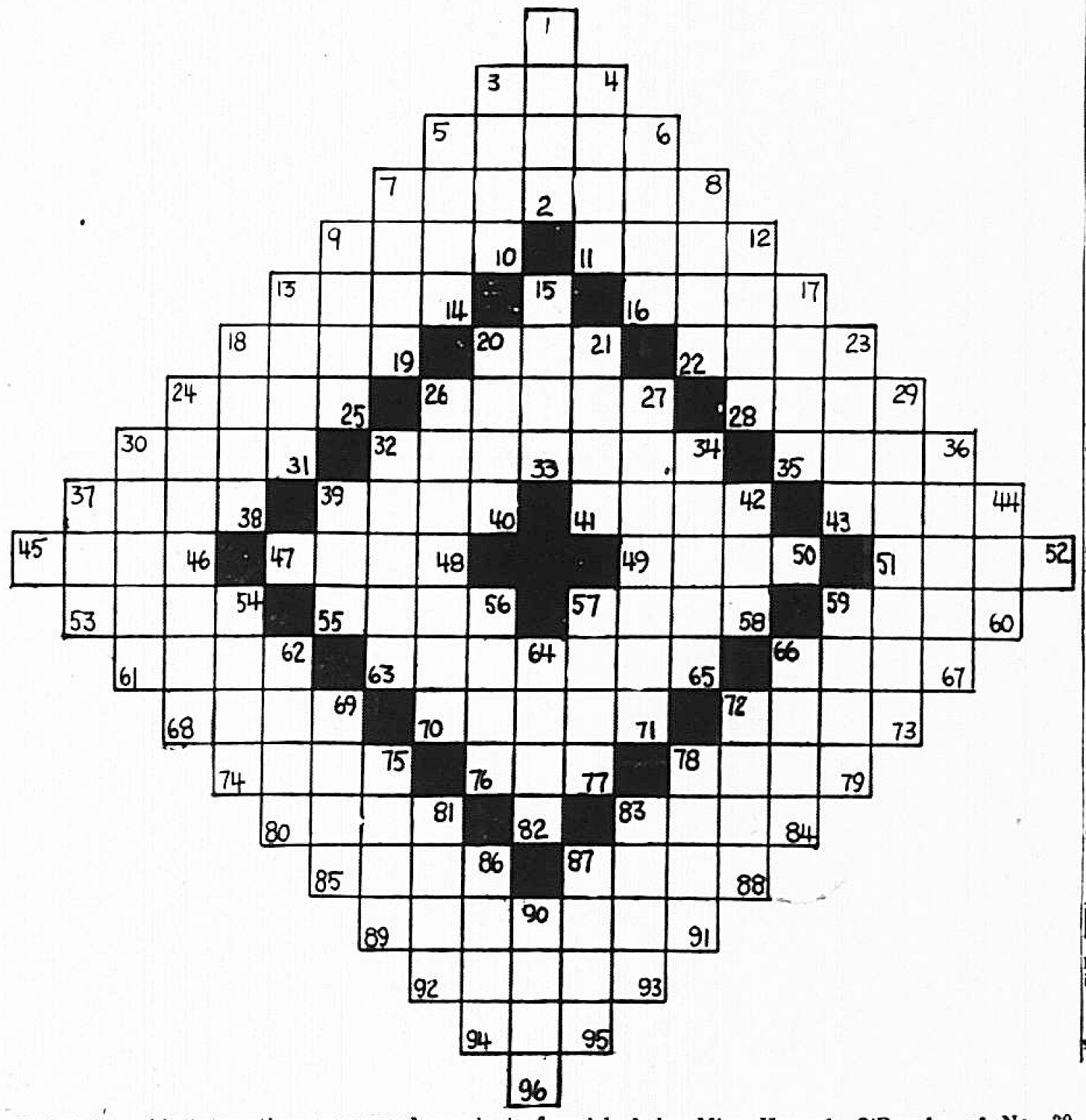

FUN published plenty of grids in Wynne’s original hollow-diamond design, some anonymous (and likely by Wynne), some by others. Another common theme at this point was nested hollow-diamond designs, which were no harder to construct, word-by-word, than the single hollow diamond:

Still, more innovative designs were plentiful. The automobile still qualified as a craze in the 1910s, so the grid below may have felt inevitable. Fun printed it with the following note:

The inventor of the cross-word puzzle printed this week calls it a Guessmobile runabout. Incidentally, he requested that his name be not used, as once before when he contributed a cross-word puzzle many of Fun’s readers sent their solutions to him.

One puzzle took the form of a swastika sign—in 1915, the swastika was still five years away from its adoption by the then-nascent Nazi party. And it was at least two decades away from coming to signify Nazism more or less exclusively. After that, the swastika (outside very limited contexts) got a lot more offensive—just as the implications of the term cross-word got less so.

Next: Lois Lane: the single era.

Wow1 Wonderful research. Thank you.

**

When the crossword puzzle constructor died, he was buried 6 down and 2 across.