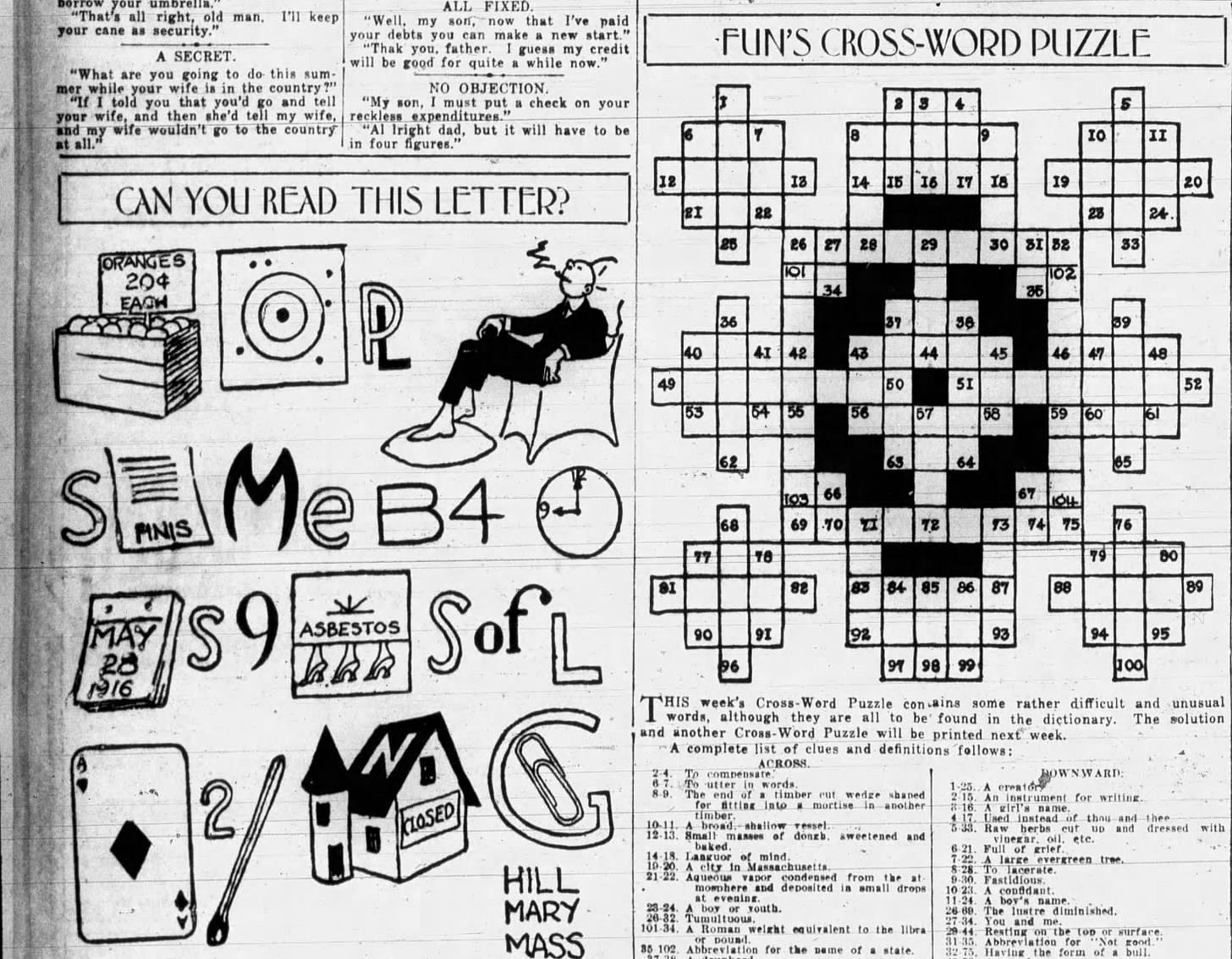

In 1916, FUN seemed to expand its reach, appearing in new papers like the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette and the Tacoma Daily Ledger. The Pittsburgh Press began publishing it on June 11. This expanded the reach of crosswords somewhat, but the crossword itself had competition now from another visually arresting kind of puzzle—the rebus.

Although “picture-writing” has been with us since ancient Sumer, the concept of a rebus, in which pictures stand in not only for words but also for their soundalikes, is more an invention of the Middle Ages. They began as clever signatures—one might have signed “T Campbell” as ☕🏕️🔔—before maturing into puzzles sometimes around the Renaissance. By the 1800s, it was well established in American life, and it would have been an altogether familiar entertainment to the audience of 1916.

It seems Arthur Wynne was hedging his bets at this point. The crossword puzzle was still popular, but there was no guarantee it would last another few years. And if it did, it might congeal into a form he didn’t recognize—literally.

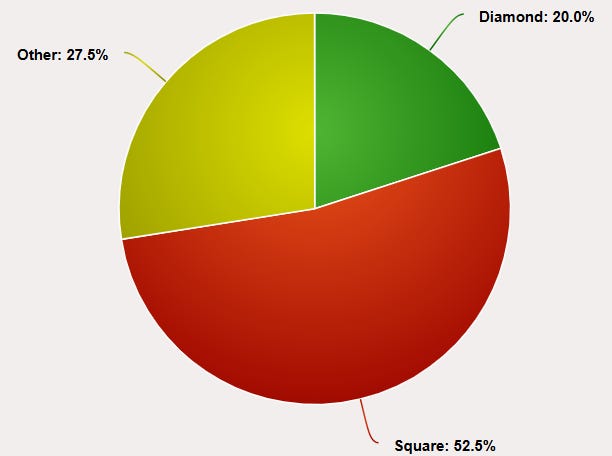

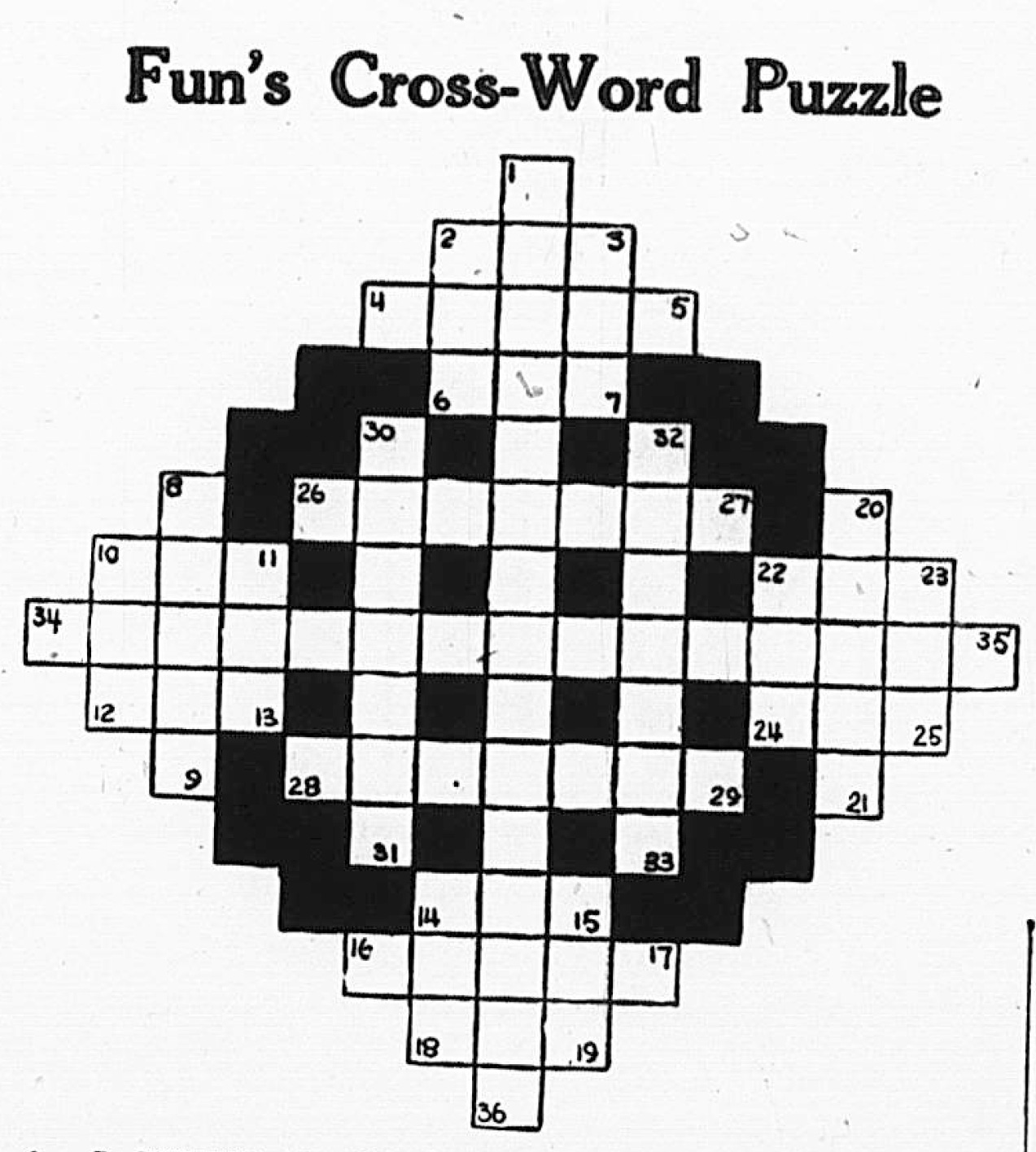

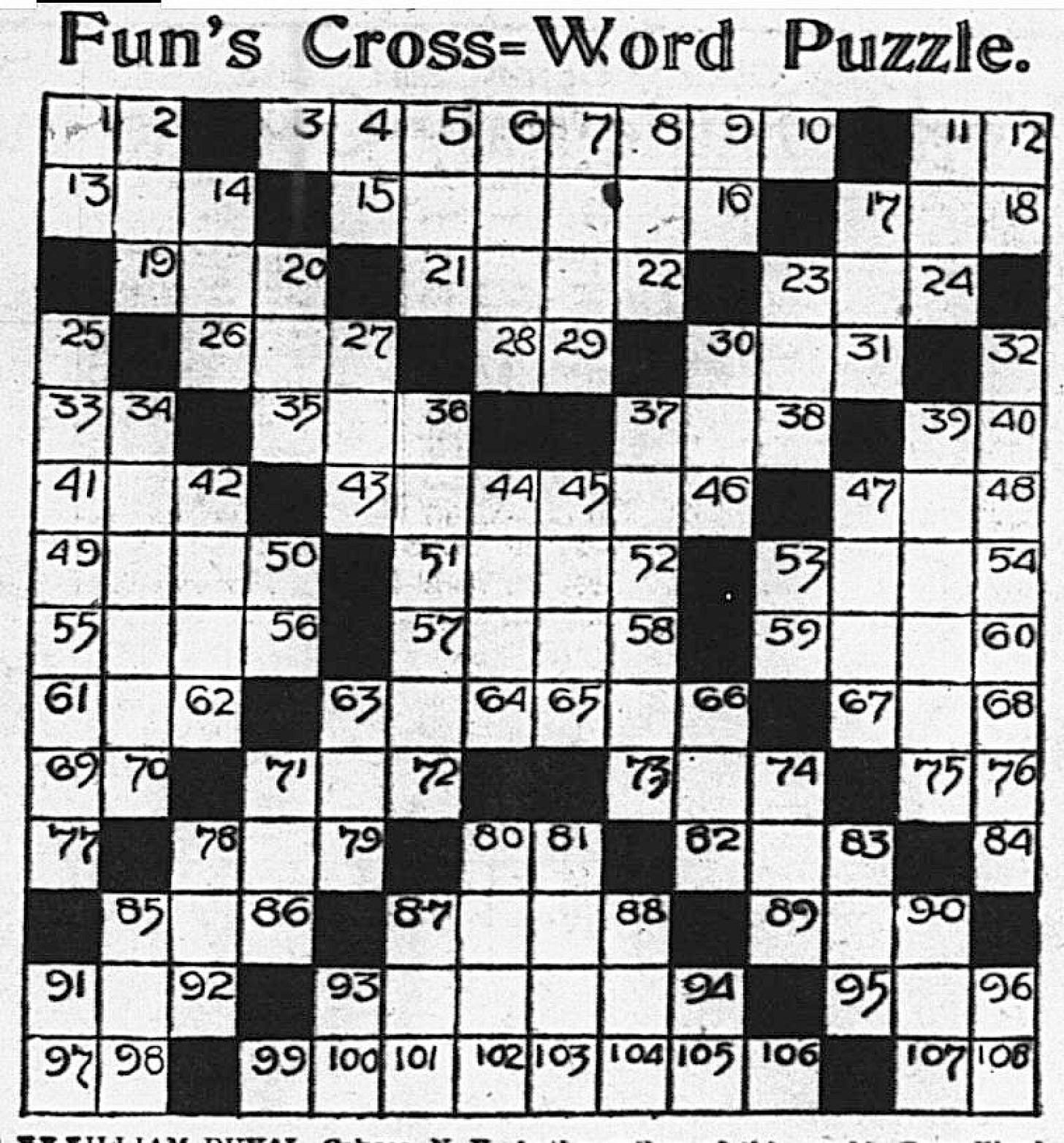

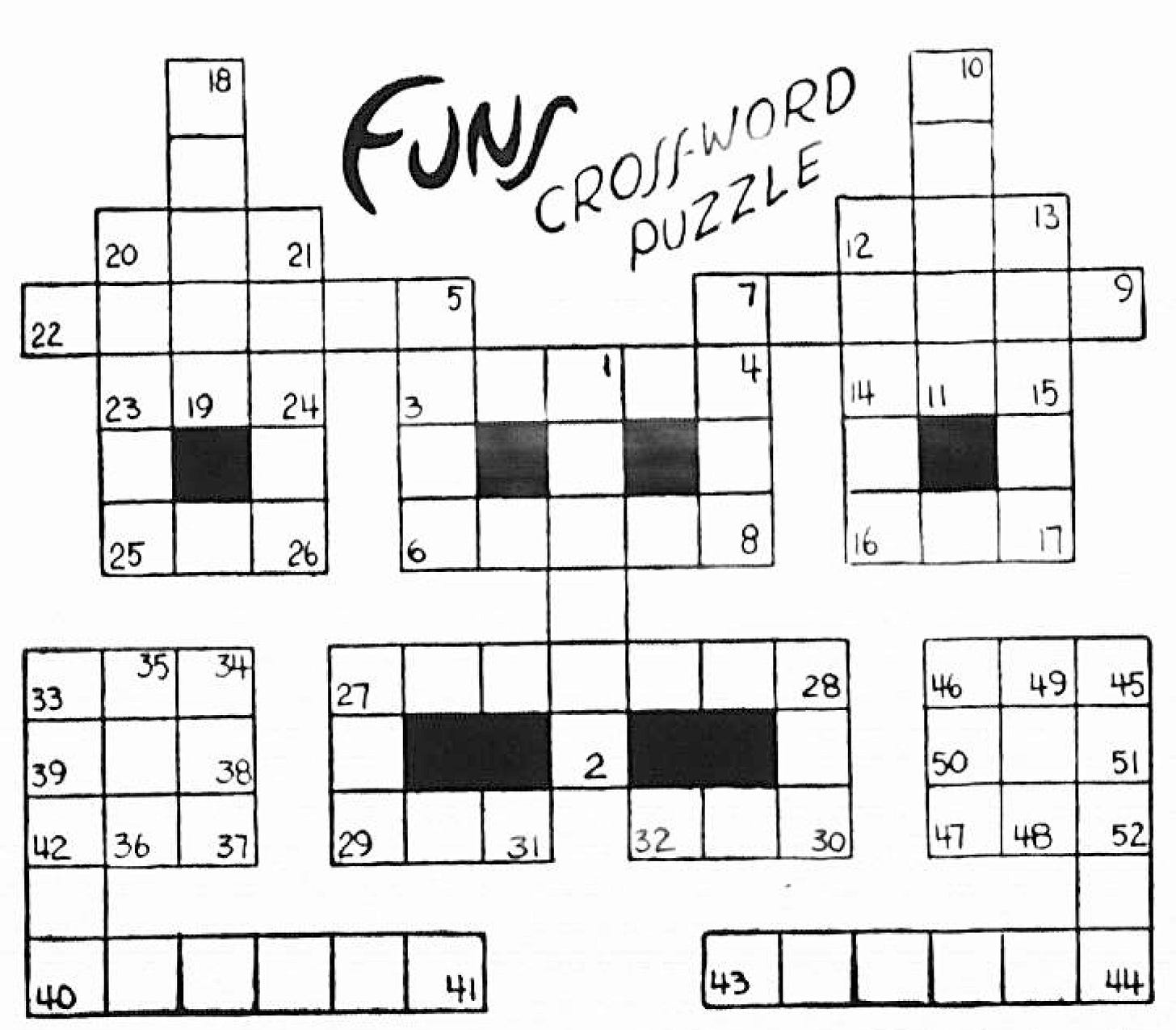

The first crossword puzzles Wynne designed were diamond-shaped, and so were many reader submissions. By 1916, though, the diamond shape seemed to be losing ground. The shape of crossword puzzles was still far from standardized, but the most likely shape for crosswords to assume was a square—which was generally more convenient for layout artists and provided more entertainment value per square inch.

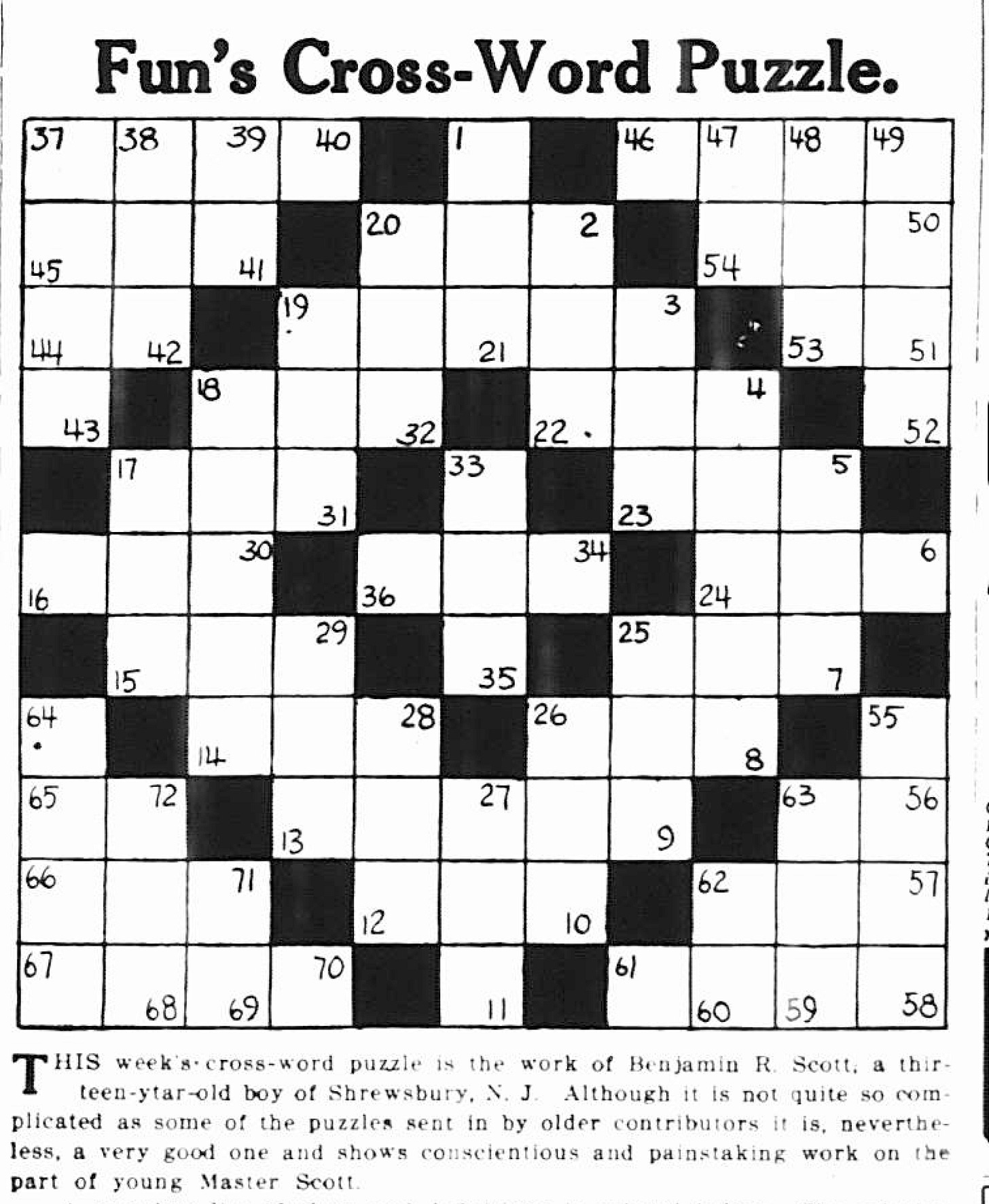

Of the forty puzzles I surveyed published during that period, eight of them were diamond-shaped, twenty-one were square shaped, and eleven were some third type (see samples below).

Although some forms seemed to contain aspects of both:

Note that the above puzzle is listed as the work of Benjamin R. Scott, “a thirteen-year-old boy of Shrewsbury, New Jersey.” That makes him about as young as the youngest crossword creator in New York Times puzzle history, Daniel Larsen.

Despite this evolution, crosswords in 1916 remained just about unknown in many parts of the United States. If a “crossword/cross-word” reference showed up in a newspaper and it wasn’t in a syndicated FUN section, it was still using the old “angry speech/swear word” definition, like the Sep 26, 1916 issue of the Decatur Herald:

Another such reference appeared in the Decorah Public Opinion on June 7 that same year:

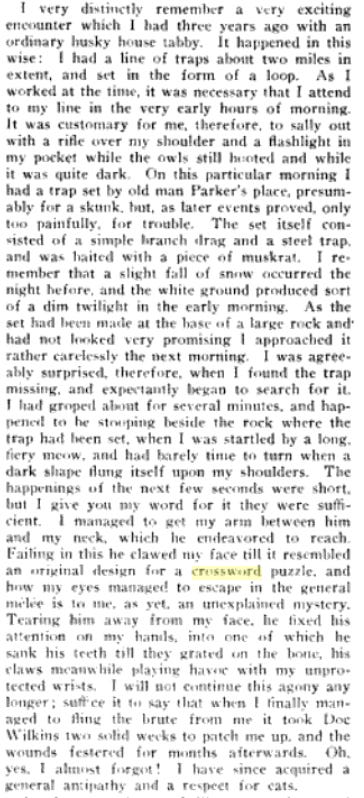

However, there was one exception to this in a specialized periodical! In “Thrills of the Trail,” in Fur News 2, February 1916, George Zebrowski described a “very exciting encounter” with an “ordinary husky house tabby,” possibly injured by a trap.

The cat attacked the author, who reported he’d had ailurophobia ever since: “he clawed my face until it resembled the original design for a crossword puzzle, and how my eyes managed to escape in the general melee is to me, as yet, an unexplained mystery.”

We now have a more complete picture of crosswords’ path from near-obscurity to national craze to fixture of international life. All thanks to Zebrowski and the angry housecat.