America’s involvement in World War II would be a turning point in the history of crosswords, expanding and solidifying their market presence. World War I, not so much. Arthur Wynne’s weekly FUN crossword chugged along but inspired no imitators. Despite later misleading claims, The Boston Globe did not publish its own crosswords in 1917.

However, it did join the Salt Lake Telegram and the aforementioned Tacoma Daily Ledger, Pittsburgh Press, and others in syndicating FUN. Then as now, syndicated papers published puzzles after their original release—with the delay varying from paper to paper.

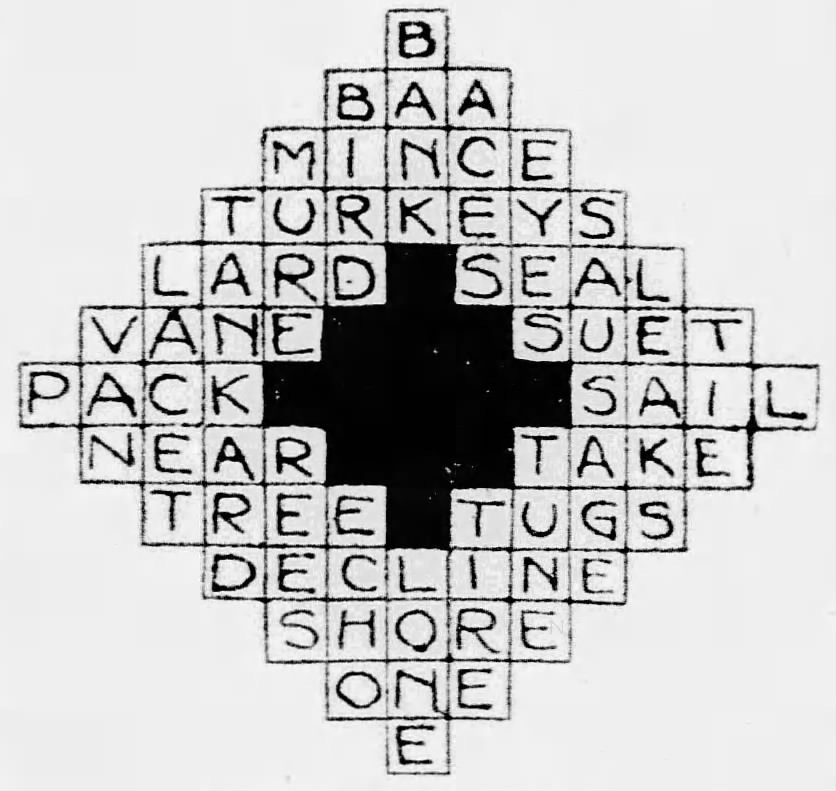

So it wasn’t until January 7 that Tacoma readers experienced a puzzle “sent in by a very distinguished contributor—none other than old Santa Claus himself. As might be expected, most of the words and definitions have a decided flavor of Christmas.” The last clue was “What no one should be at Christmastime” (LONE). Some answers—MINCE, TURKEYS, LARD, SUET, TANKARD, SAUSAGE—remind us Christmas used to be more of an eating holiday.

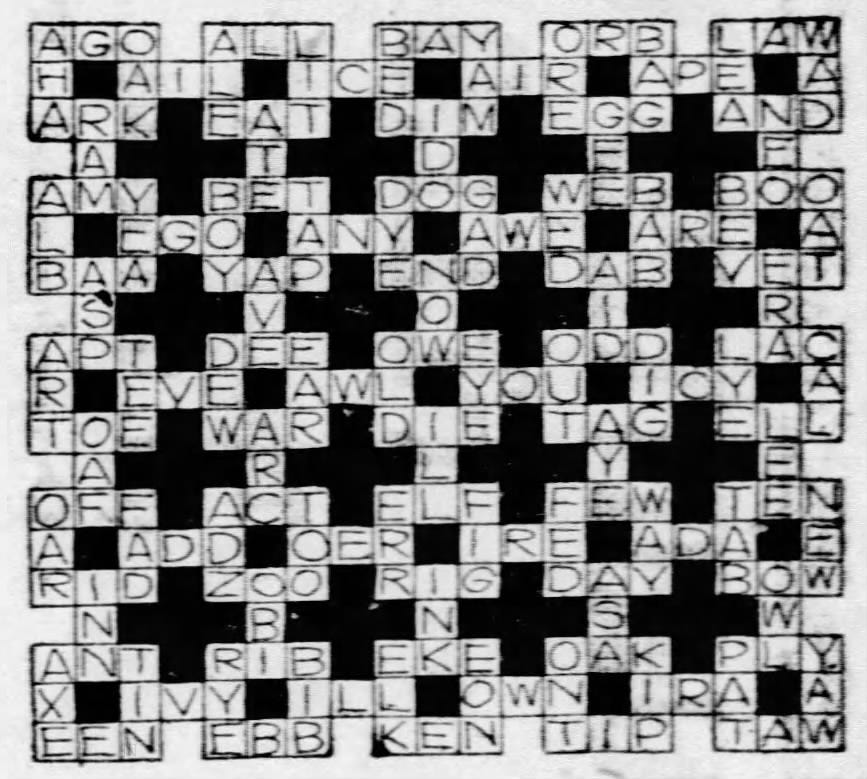

The puzzle was a throwback in more ways than one. Perhaps because of the complications of syndication, 1917 featured no other holiday-themed compositions, and non-square crossword designs were growing rare. Of the 52 syndicated puzzles I surveyed for the year, 45 were squares or near-squares. (About a third of those featured diamonds inside the larger square design.) Four of the exceptions, like this rectangle, came out near the beginning of the year.

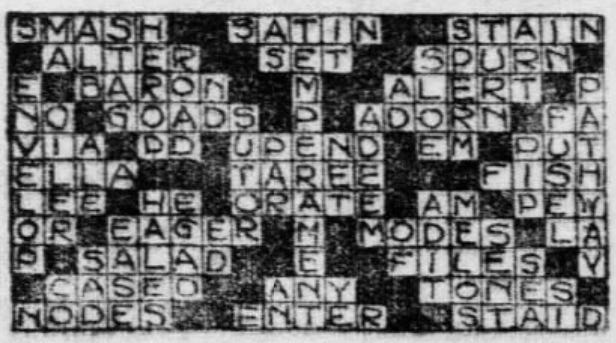

With words like TAREE, SUTOR, and ADEEM as load-bearing central entries, this grid is nowhere near what modern editors would find kosher. Even the experimental designs from this period often didn’t show great technical skill.

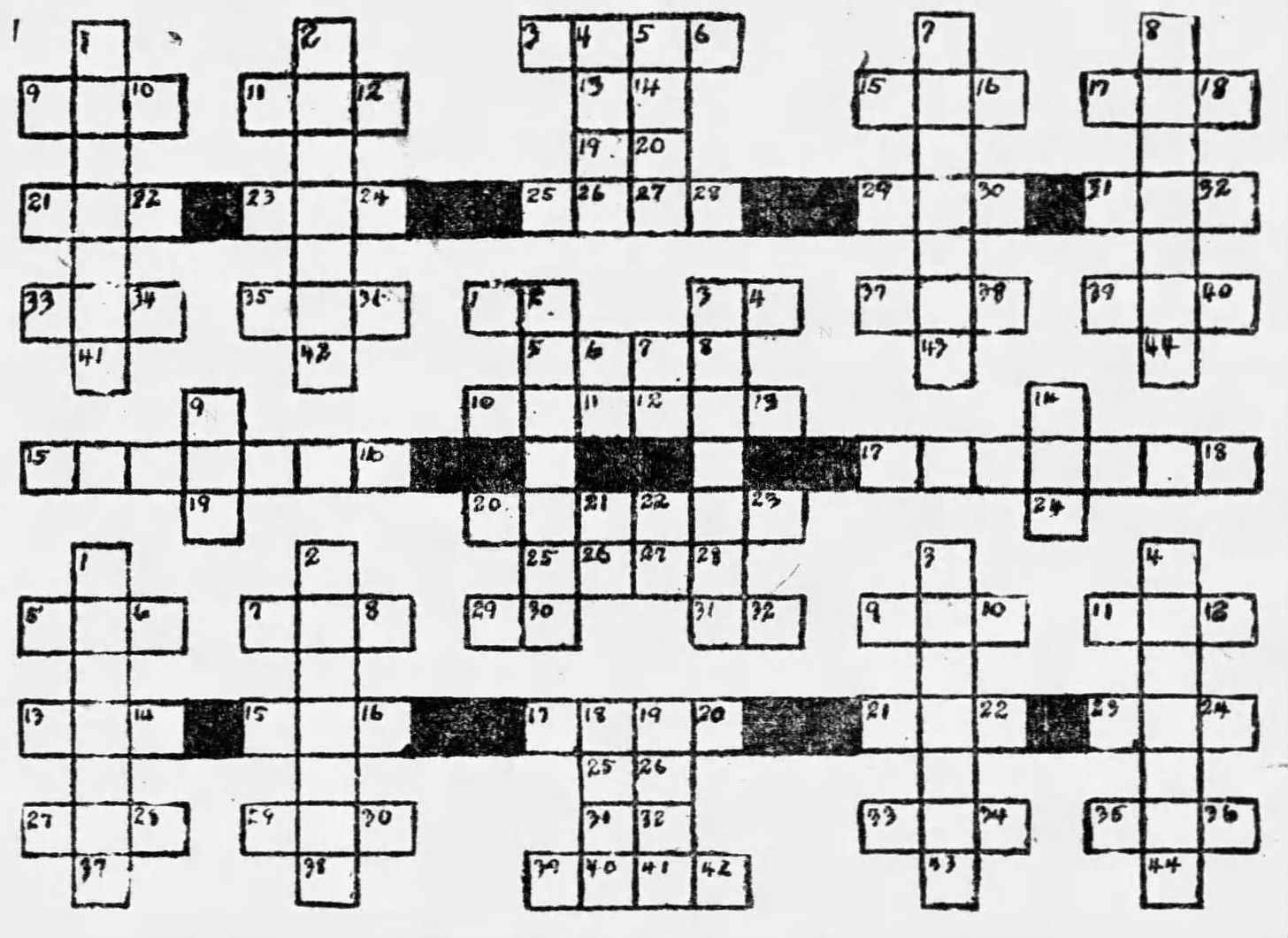

The most interesting puzzle design of 1917 might be the Edwin A. Lyon creation below. It may be the only puzzle published in major venues to use nothing but three-letter answers. Almost all its choices are common vocabulary today.

Of surveyed puzzles, exactly half (26 of 52) were anonymous—assuming Santa Claus didn’t really write that one puzzle. Seems like he’d be a little busy around Christmastime. Of the remainder, 7 had women’s names, 11 had men’s, and 8 used initials, e.g., “R.P. Harvey.” (Three also listed themselves as “Mrs.” or “Miss.”)

A strong uptick in male names toward year’s end might reflect the United States joining the war. Some of those constructors may have been bored and anxious soldiers seeking distraction before deployments—or after them. One author was listed as “Private Arthur R. Gormley, Post Hospital.”

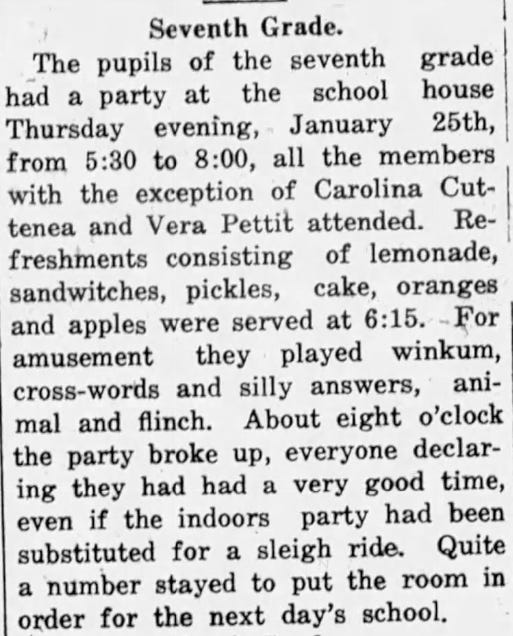

Mentions of “cross-words” outside FUN were still more likely to mean “words spoken in anger” than “puzzles solved for fun.” There was, however, this curious citation in the Sidney Herald, February 7. Part of a series of “School Notes” provided by Mae Pearce, it’s a window into an older and sometimes delightful world:

“Winkum, cross-words and silly answers, animal, and flinch.” A little research clarifies some of these. Flinch is not the schoolyard game, sometimes verging on bullying, in which one makes threatening moves and punishes anyone who flinches—it’s a card game created in 1905. Winkum is a variant on musical chairs.

But “animal”? Is that a version of Twenty Questions where the “animal, vegetable or mineral?” question comes pre-answered? A version of Werewolf? More-specific charades?

And “cross-words and silly answers”? A lot of modern crosswords have silly answers. Did this game anticipate that practice? Don’t know. I doubt it had much to do with any puzzles published in FUN, though.

Unless TAREE, SUTOR, and ADEEM were popular slang terms among schoolchildren of the 1910s.

The word "tankard" originally meant any wooden vessel (13th century) and later came to mean a drinking vessel. The earliest tankards were made of wooden staves, similar to a barrel, and did not have lids. A 2000-year-old wooden tankard of approximately four-pint capacity has been unearthed in Wales.

DRANK AT TANKARD