In 1918, there was still only one regular crossword feature—syndicated from the New York World—but it continued a slow bloom in 1918, showing up in more and more papers. While it offered an escape from the war, the war left a noticeable fingerprint on it.

The theory that the war led to more male crossword designers has some supporting evidence in 1918 bylines, which included 6 female names, 15 male ones, and 7 listed with an initial in place of a first name. The remaining puzzles were anonymous. Syndication partners sometimes dropped bylines when they reproduced the crossword for their own pages. The Pittsburgh Press (then spelled The Pittsburg Press) featured such bylines whenever they appeared from the source; The Boston Globe did not.

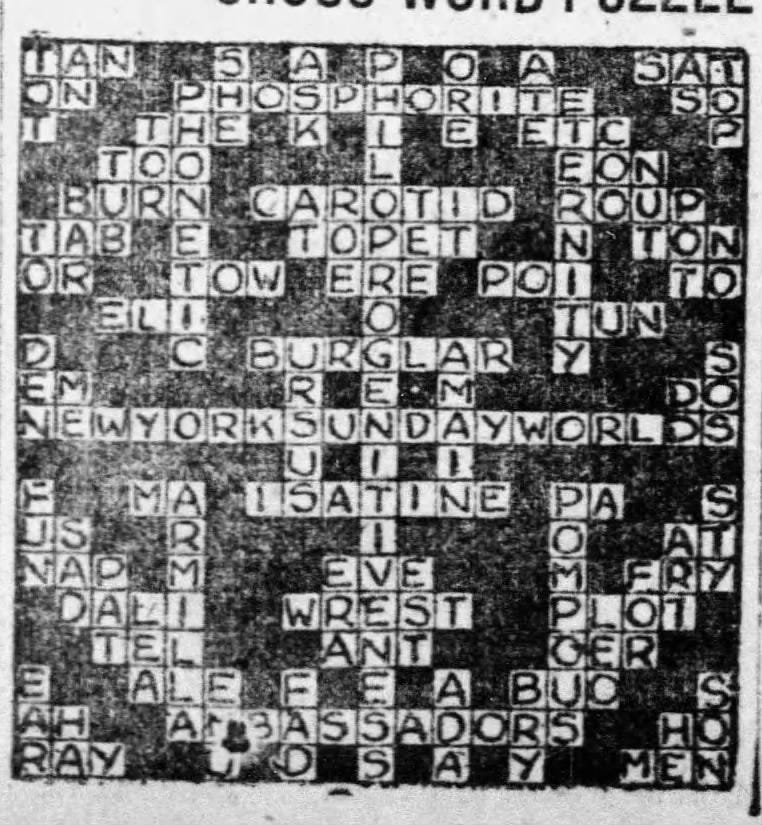

Considering the puzzle was now reaching a wider audience in syndication than in its original venue, it was ironic that this March grid included NEW YORK SUNDAY WORLDS as an answer, clued with “They bring you FUN.” Note the demanding nature of the other long answers: PHOSPHORITE, AMBASSADORS, PHILOPROGENITIVENESS (“The love of offspring”).

The Los Angeles Evening Express included this note before becoming the latest outlet to syndicate FUN’s crossword:

A Feature June 9: The Cross-Word Puzzle will afford lots of fun for nimble-witted youngsters and grownups. Work out a set of answers and see how they correspond with the correct definitions published a week later in the Magazine Section.

This may be the first instance of the puzzle being advertised as “fun for the whole family.” On the one hand, FUN featured cartoons, simpler puzzles, and jokes likely to delight “nimble-witted youngsters.” On the other, it’s hard to imagine even the nimblest-witted 1918 schoolchildren rattling off PHILOPROGENITIVENESS in everyday speech. “Mother won’t let me try on her lipstick! What a beastly lack of philoprogenitiveness!”

Actually, that’s easier to imagine than I thought.

But you take my point. It’s a word for the advanced vocab quizzes.

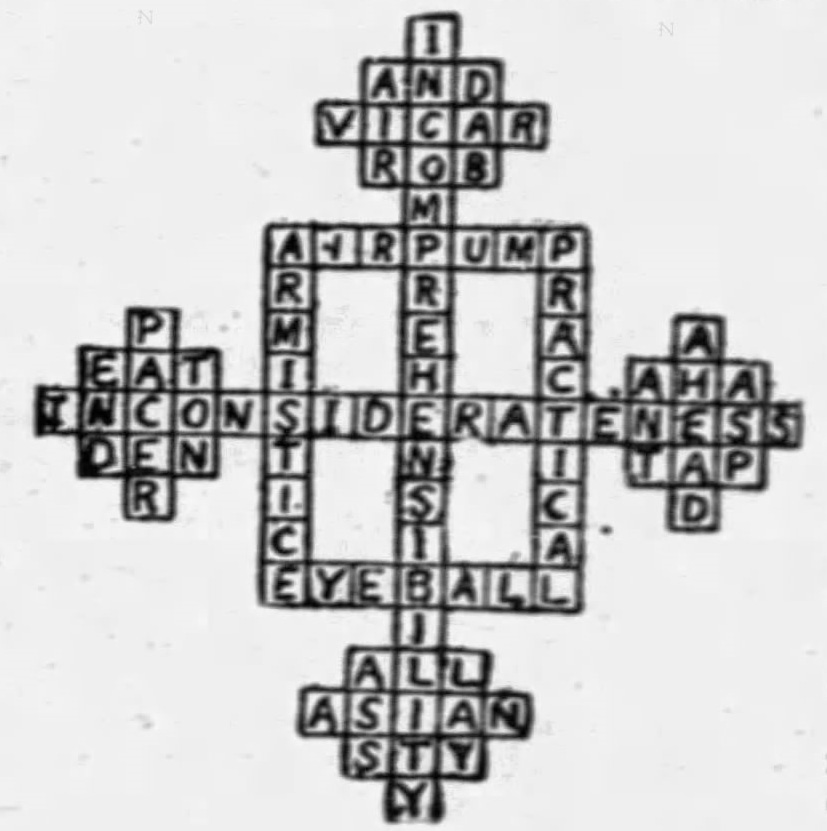

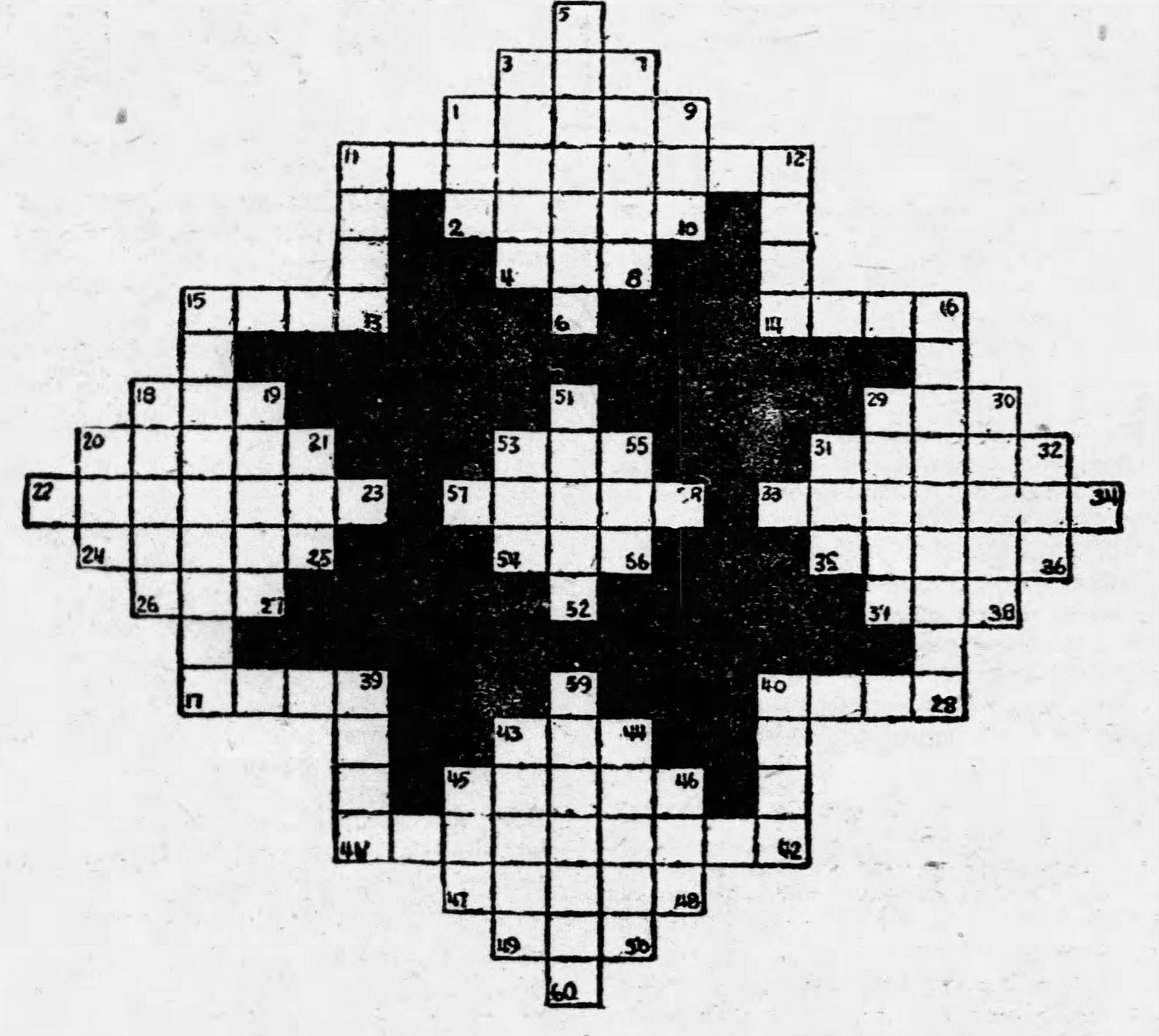

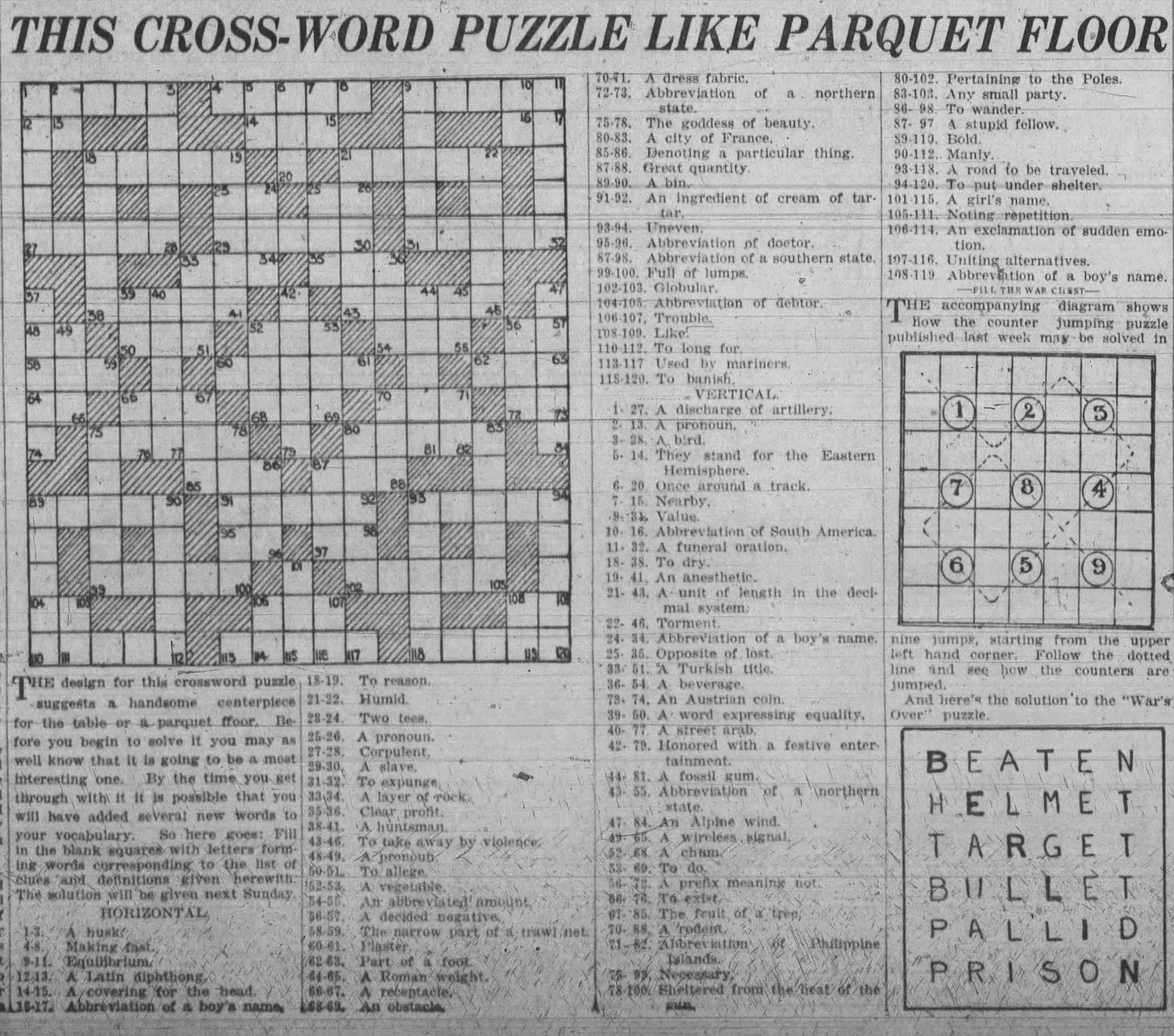

In late 1917 and early 1918, it had looked like crossword design was settling down into staid squares and diamonds-in-squares. But it got more creative again as 1918 wore on. More circular designs came into fashion—both within squares and on the exterior—and late in the year, exterior diamonds made a reappearance.

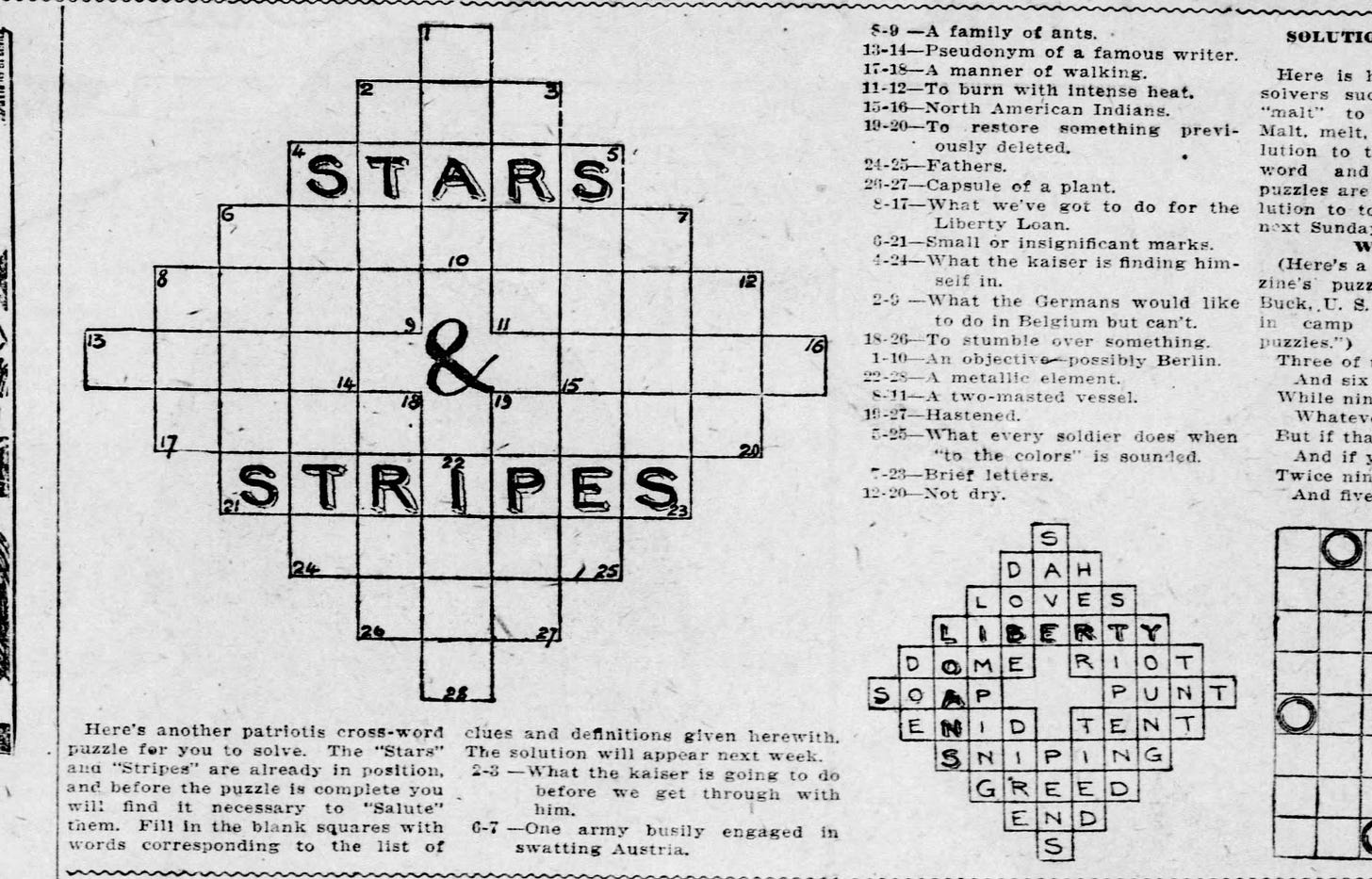

Two diamonds, probably authored by Arthur Wynne, were connected with wartime propaganda. The words auto-filled into the grids were STARS and STRIPES in one, LIBERTY/LOANS in the other. Liberty loans were what later generations would call “war bonds.”

Another grid, published in the September 1 Globe, had the 1-Across clue, “Denoting adherence to the greatest country in the world.” Answer: AMERICANISM. The prior 1-Across had been BATTLE. (A later grid included the word ARMISTICE.)

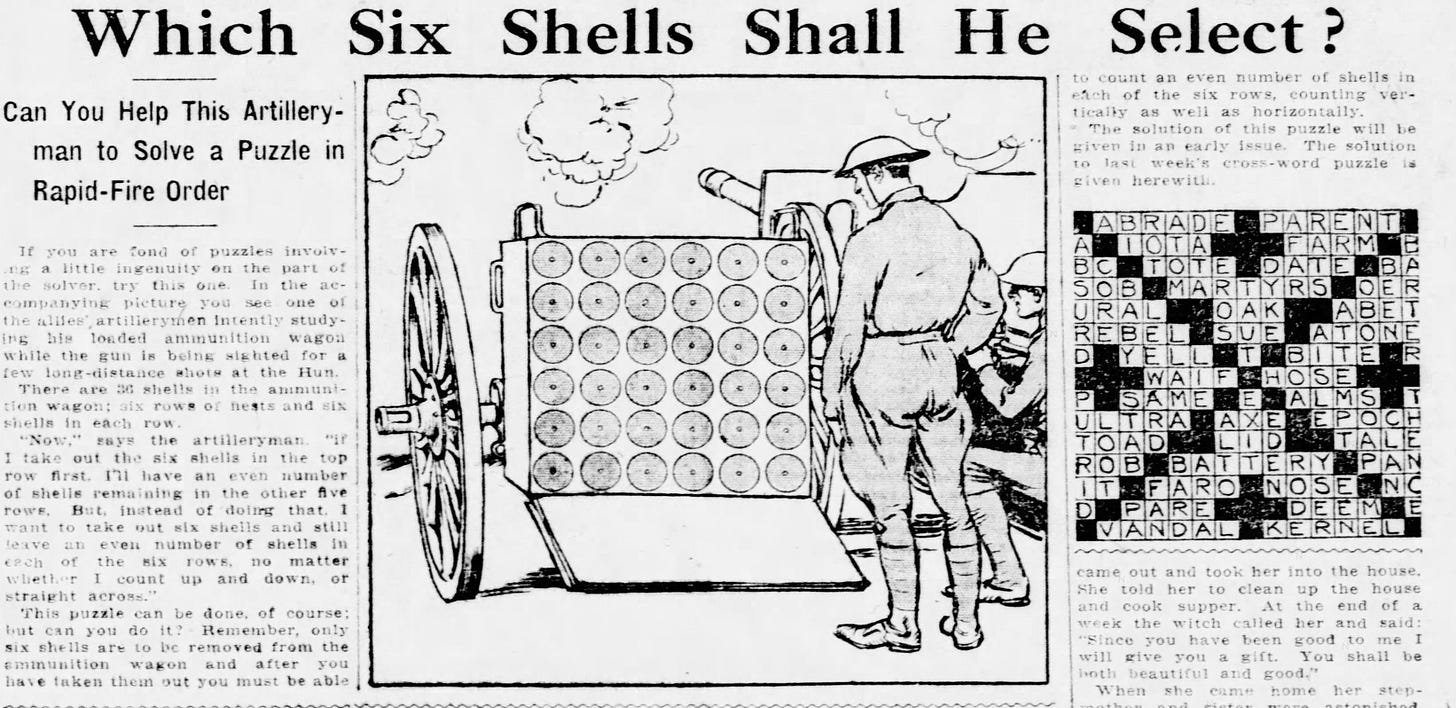

Despite the crossword’s popularity, FUN replaced it on at least two occasions in 1918, running other puzzles instead. One was a geometry puzzle with an obvious wartime influence—and more than one right answer. (Remove six artillery shells so that an even number remains in each row and column.)

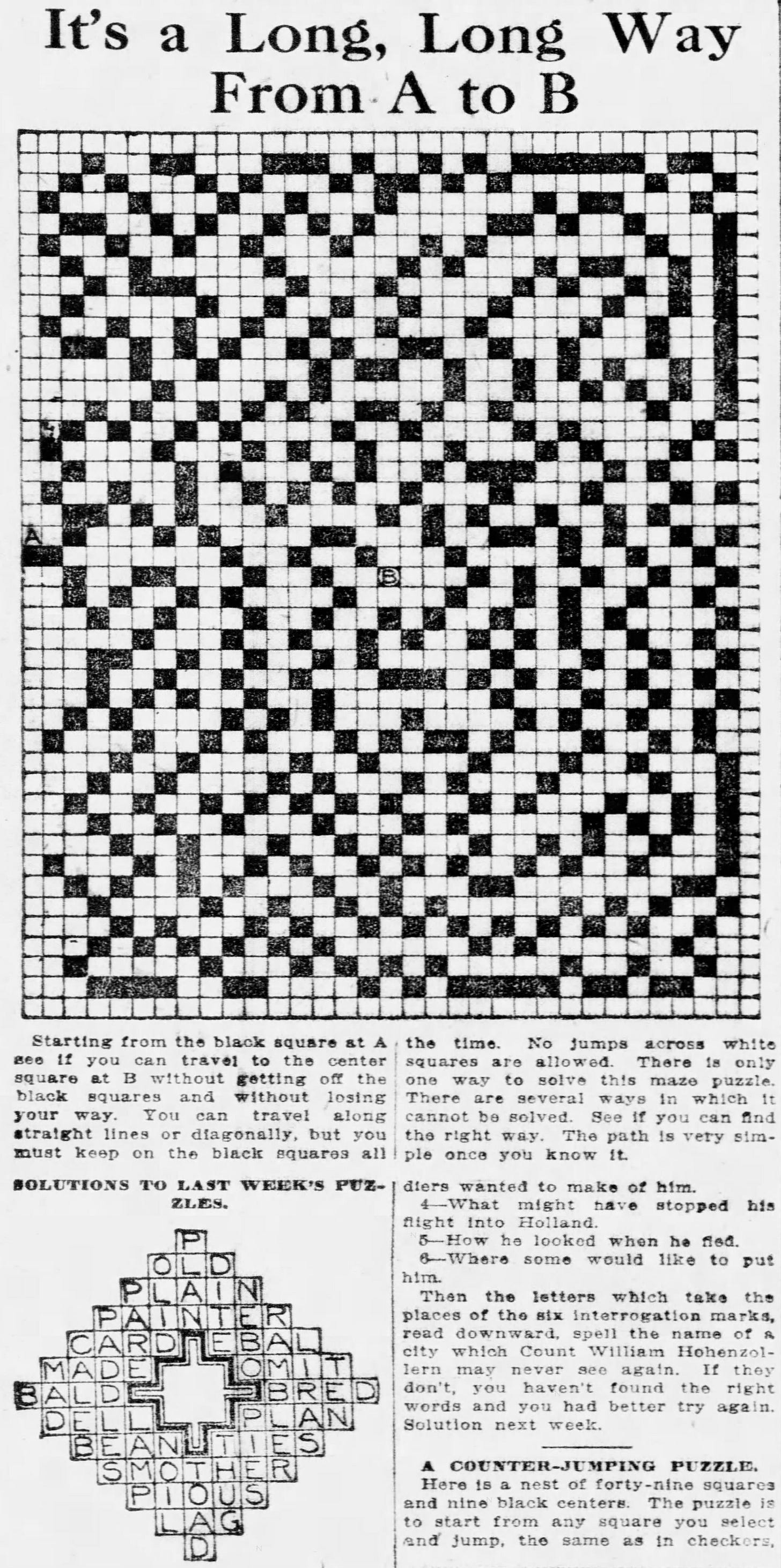

The other was a maze that superficially resembled a crossword:

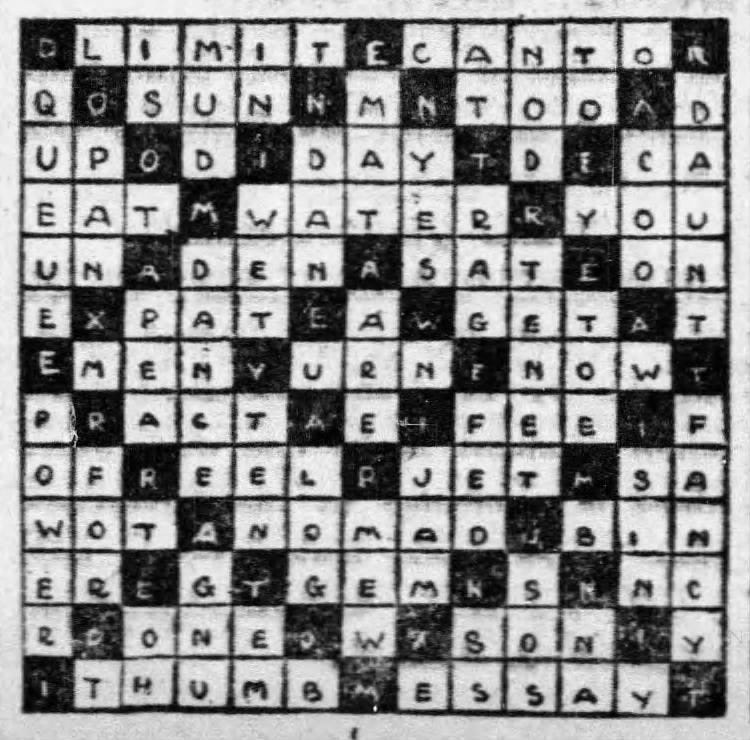

Other notable experiments of the year included two separate puzzles that offered additional clues and answers within the areas normally marked as negative space. Is this the only mainstream crossword that ever required a white pencil to solve?

The cultural impact of crosswords remained small. Outside of FUN, citations for “crosswords” around this period often continued to mean “angry words” or “acrostics.” One exception is a school report from The Jefferson County News, Jun 27, 1918:

During this second year of our high school work each member of our class has delved into the depths of Algebra and have learned the Binomial Theorem and are now completing the "crossword puzzles" officially called Logarithms.

This citation is interesting, because it shows crosswords entering the consciousness of younger people, but also that they weren’t considered “easy” puzzles. Even well-educated teens who knew their way around the binomial theorem used them as a metaphor for tough challenges.

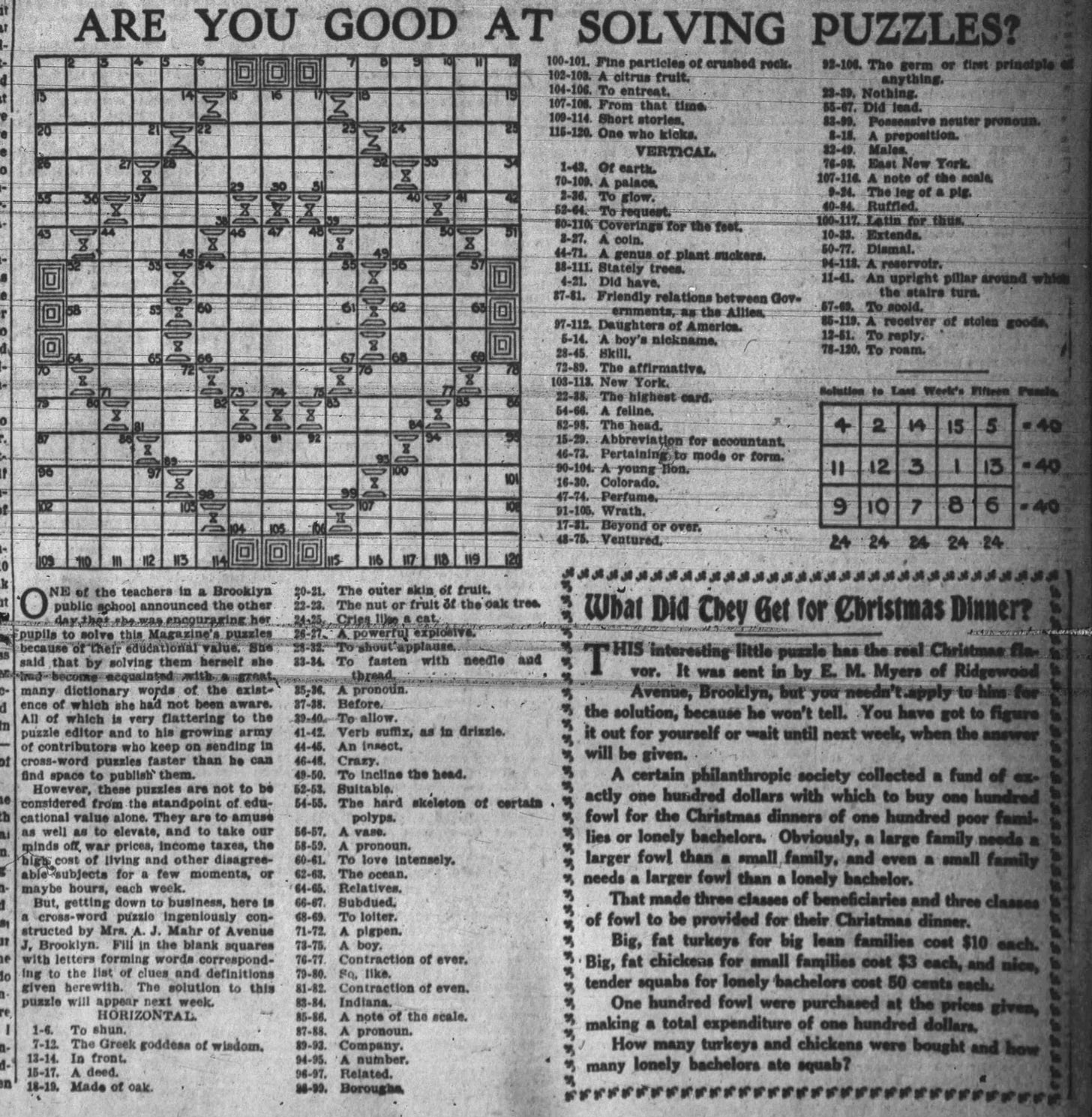

At the end of the year, a syndicated puzzle ran with a long intro in some papers:

One of the teachers in a Brooklyn public school announced the other day that she was encouraging her pupils to solve this Magazine’s puzzles because of their educational value. She said that by solving them herself she had become acquainted with a great many dictionary words of the existence of which she had not been aware. All of which is very flattering to the puzzle editor and his growing army of contributors who keep on sending in cross-word puzzles faster than he can find space to publish them.

However, these puzzles are not to be considered from the standpoint of educational value alone. They are to amuse as well as to elevate, and to take our minds off war prices, income taxes, the high cost of living, and other disagreeable subjects for a few moments, or maybe hours, each week.

The more things change…

Next: The most popular superhero of the 1940s was—what’s his name, again…?