As 1920 began, the crossword vanished.

For two months, the New York World’s FUN section and its syndication partners offered up no new crosswords—except The Boston Globe, still syndicating on a schedule far removed from anyone else’s. (Globe fans reported making yokes out of the grids after use.) In late February, World crosswords resumed with this note:

That the cross-word puzzle has not lost its popularity is attested by the numerous letters which come to The Sunday World each week asking why that feature has been omitted from recent issues. The answer is, of course, that we are crowded for space and are often obliged to omit features that we should like to print…

“What else could we do? There was just no space on the pages!” That might explain a week or two's absence, but eight? What was really going on here?

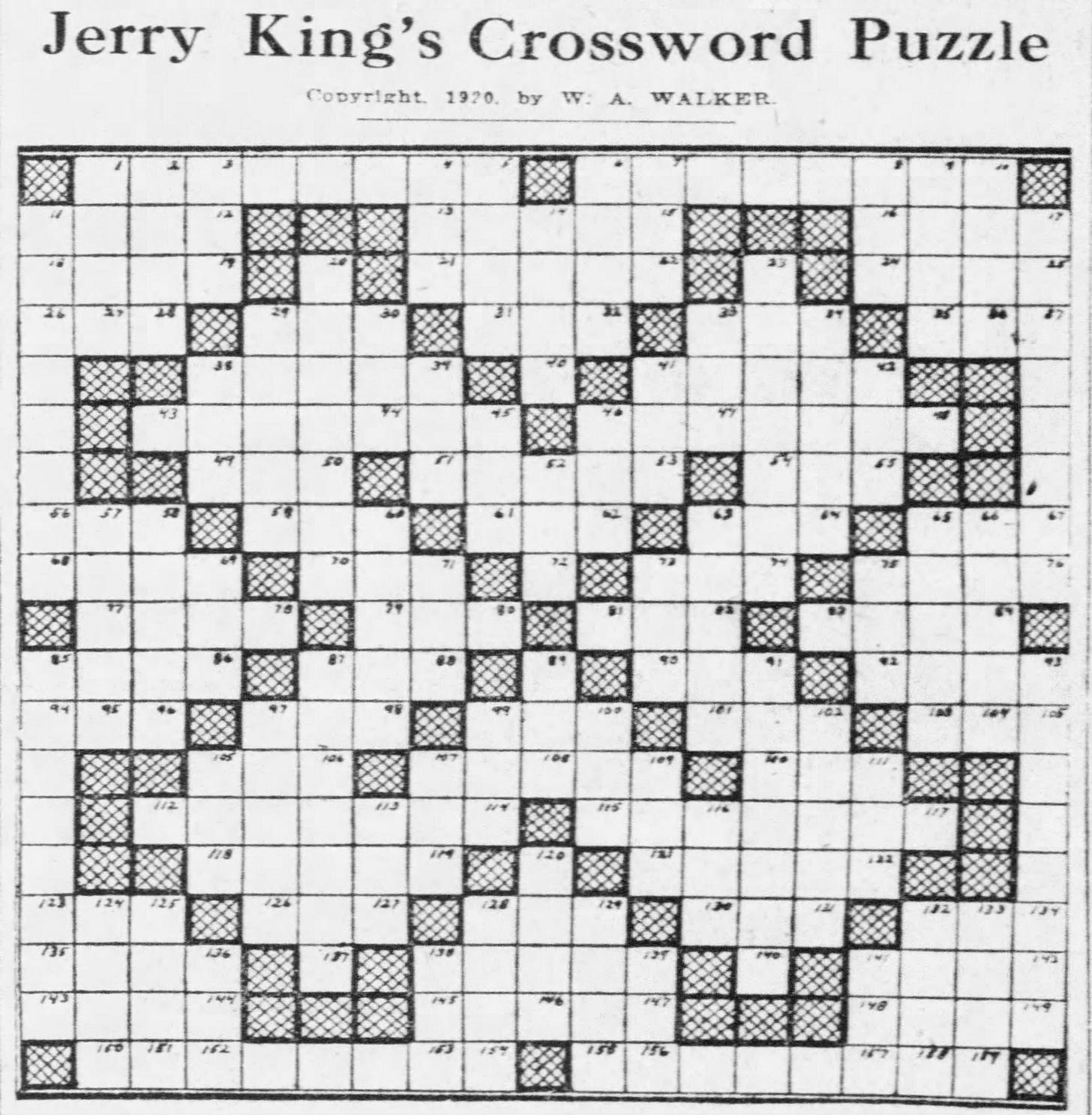

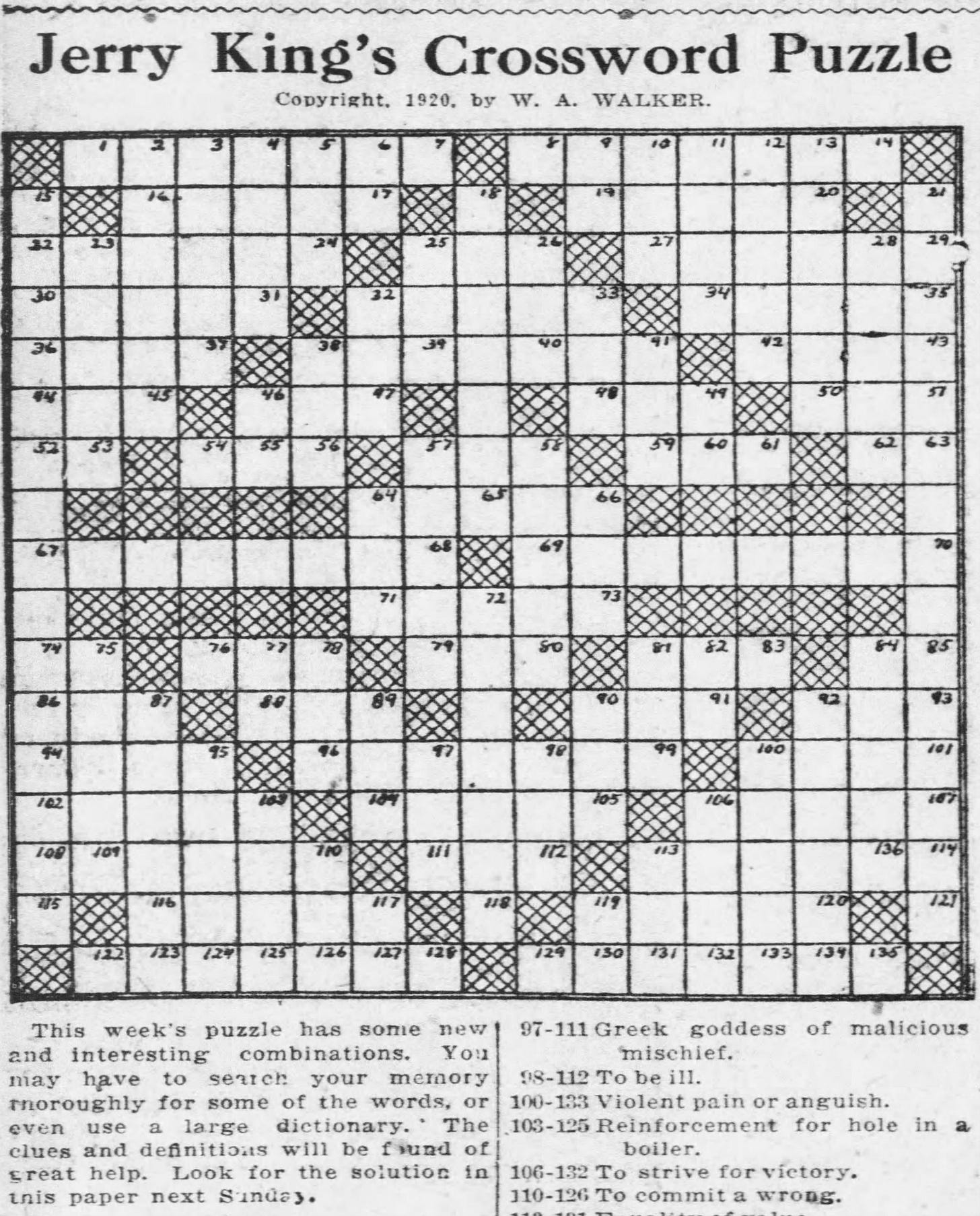

We’ll come back to that question. Regardless of cause, there were consequences. Walter A. Walker registered a copyright that winter through The Pittsburg Press for “Jerry King’s Crossword Puzzle.” In mid-March, the Press and The Minneapolis Journal began running it in the World puzzle’s place, and The Vancouver Sun picked it up too. (Others may have, also—searchable newspaper archives are far from comprehensive.)

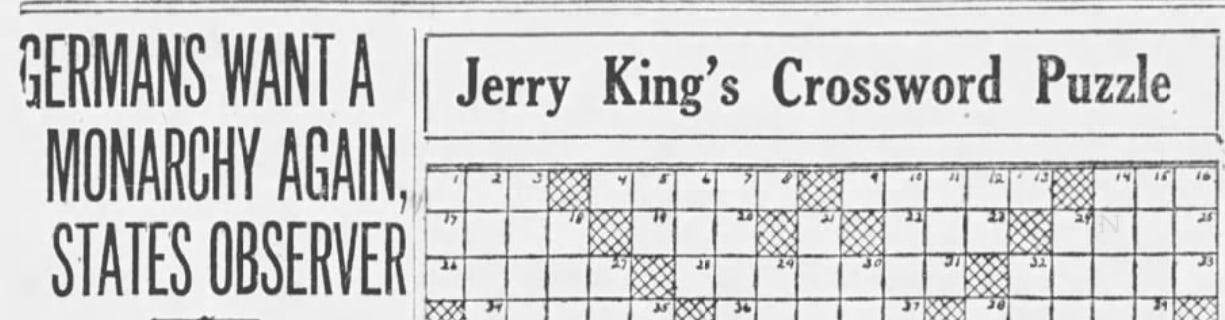

“Jerry King” was likely a pseudonym. The copyright was in Walker’s name, “Jerry” was slang for German then (too archaic to be offensive now), and this headline accompanied one puzzle in the Sun:

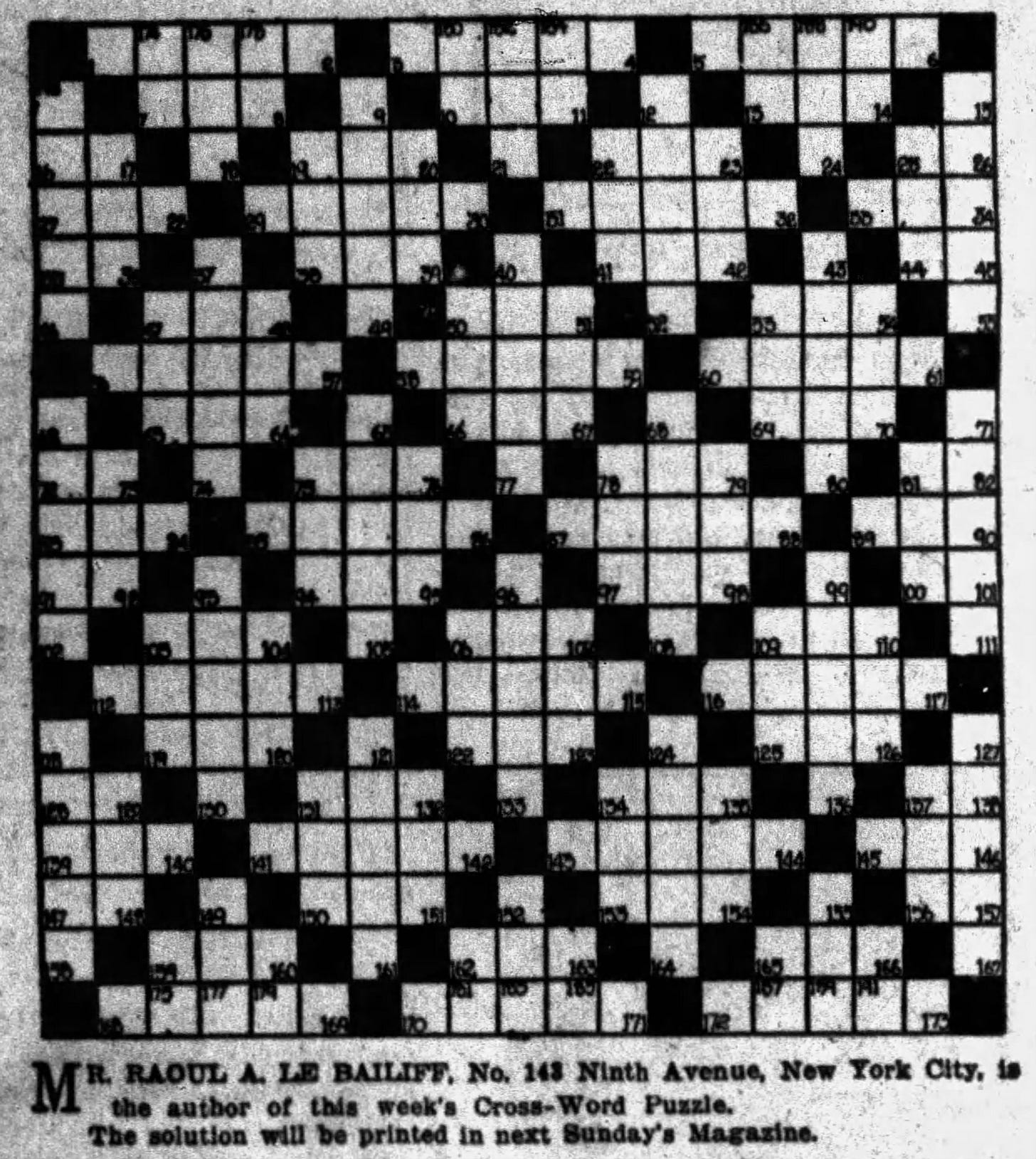

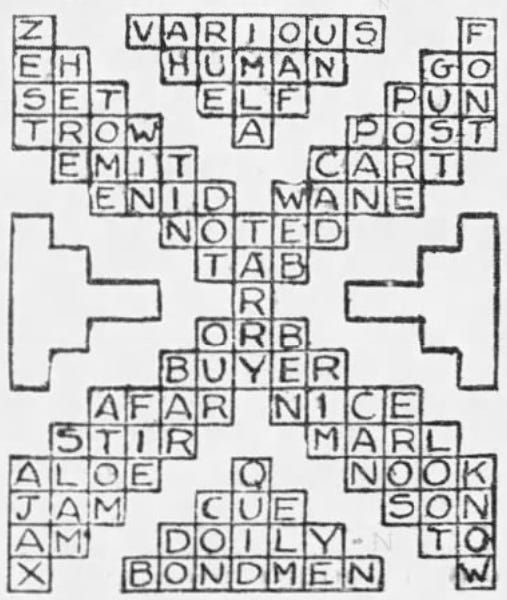

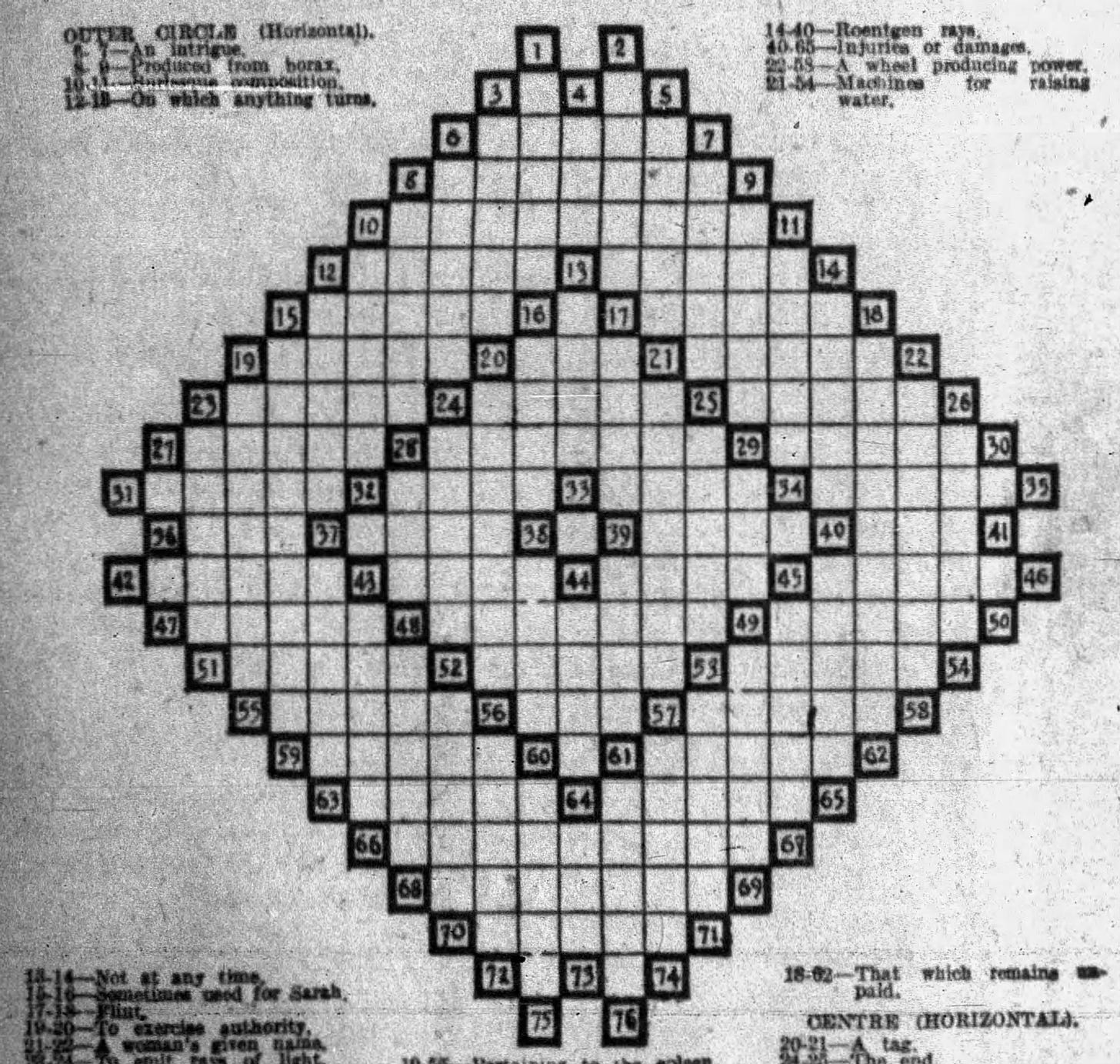

The puzzles did seem like the work of one hand: most used a distinctive hand-drawn crosshatch for black squares, and early designs tended to be more “connected” than the World’s, which could go as far as an astonishing 24 closed-off sections:

Further details about Walker are lost to history.

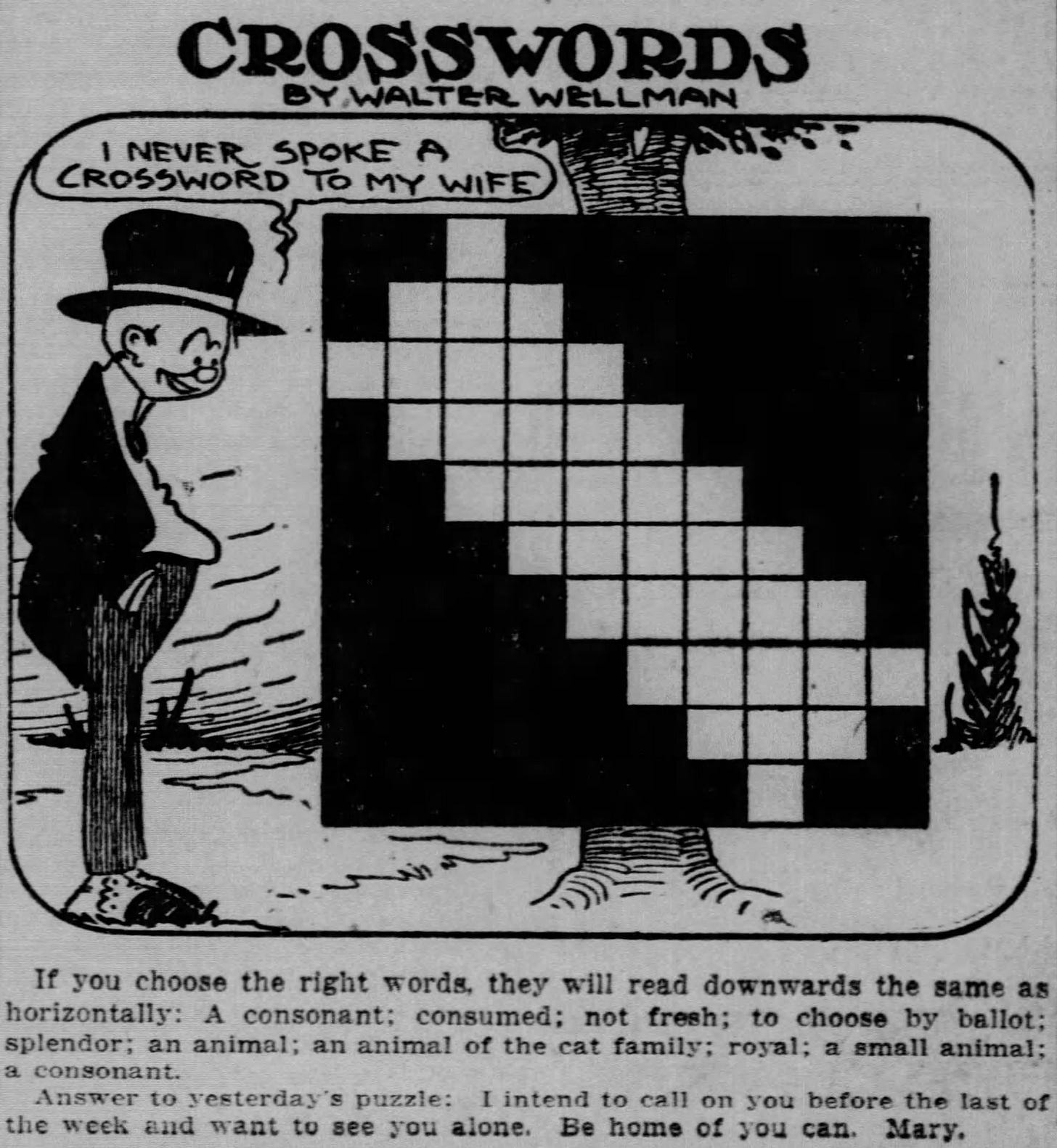

About cartoonist Walter Wellman, more is known: he had a long list of credits in newspapers and magazines. His contributions to the World began in 1905. By 1920, he was a few years from settling into greeting card illustration, but he drew fusions of crosswords and cartoons, the most “crosswordy” of which is below.

After its hiatus, the World continued its user-generated content strategy, which brought forth more innovations than its rivals. Joseph C. Taylor produced the first pangrammatic grid—or at least the first advertised as such, below.

By summer, the World was marketing an “Ingenuities” puzzle section with an aggressive subtitle—“Are Your Wits Equal to Them?” It also published “Hints for Crossword-Puzzle Makers” to inform submissions:

Do not make your diagram too large. We prefer to have them not more than twenty squares wide and about the same in depth.

One diagram is sufficient. You do not need separate ones for the numbers and letters. Put both on the same diagram, but letter them distinctly so that there will be no confusion.

Arrange the words in your puzzle so that they cross each other at as many points as possible, in order that each word found will help the solver find others.

Avoid words from foreign languages unless they are so commonly used that they have been adopted into the English language.

FUN would publish a 21x21 by year’s end.

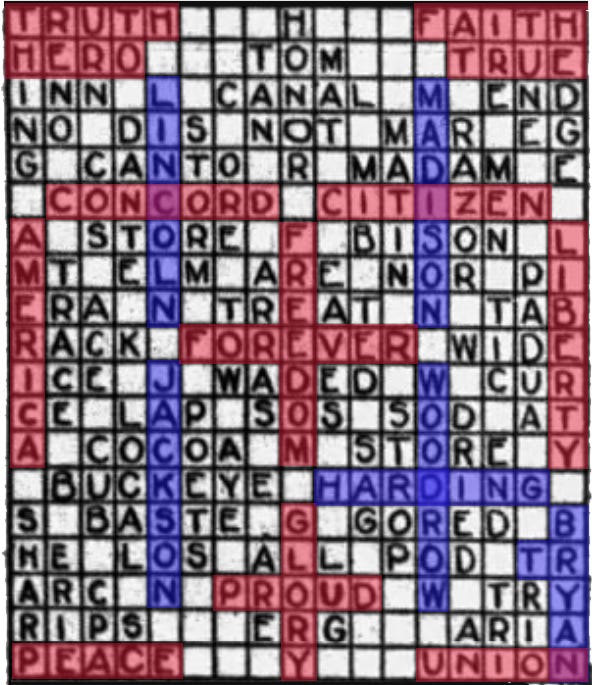

W.W. and L.T. Spencer composed the presidential puzzle below, including four presidents and two candidates. Warren G. HARDING would get elected that fall and crossed outgoing president WOODROW Wilson. (The initials T.R. got bonus credit.) “Occupying prominent positions in the diagram,” read the introduction, “are several words expressing the ideals for which our country stands.”

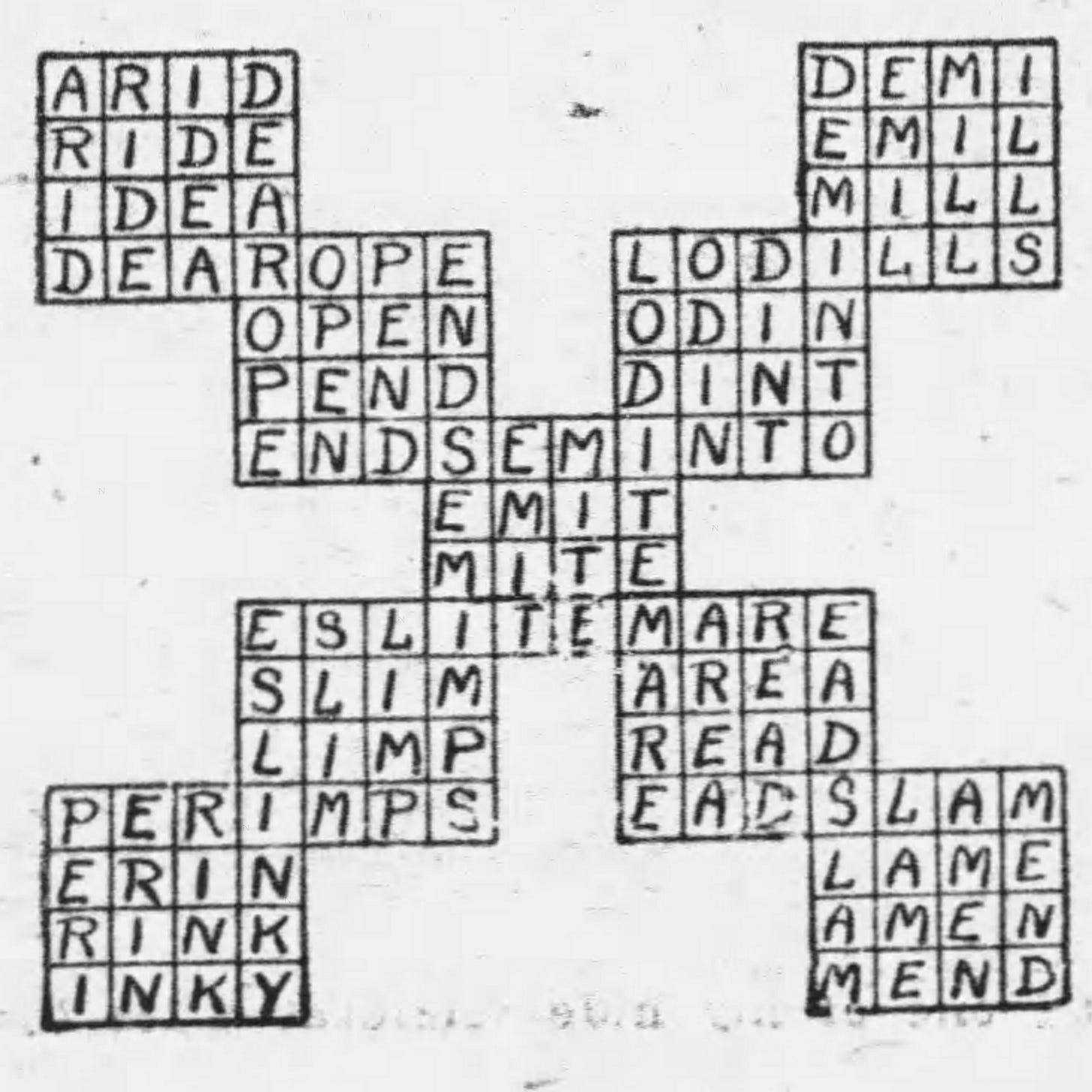

The FUN grid below isn’t one crossword but a set of overlapping progressive word squares. The first has the words ARID, RIDE, IDEA, and DEAR, each reading across and down, the last three letters of each word supplying the first three letters of the next. Same goes for ROPE-OPEN-PEND-ENDS, which overlaps the first square at the R. And so on.

Margaret Oliver’s grid experimented with numbers in “black” squares instead of the white ones.

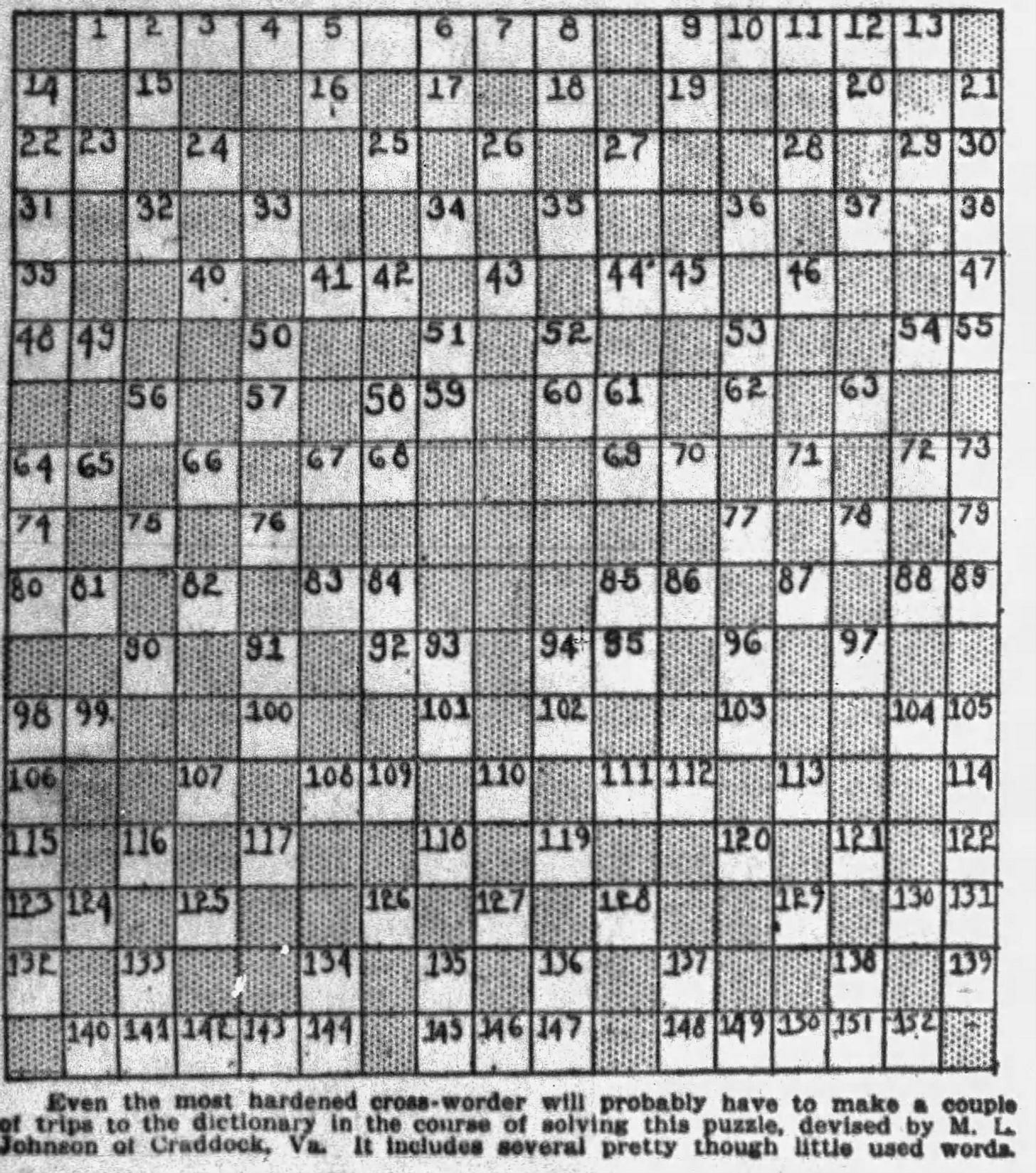

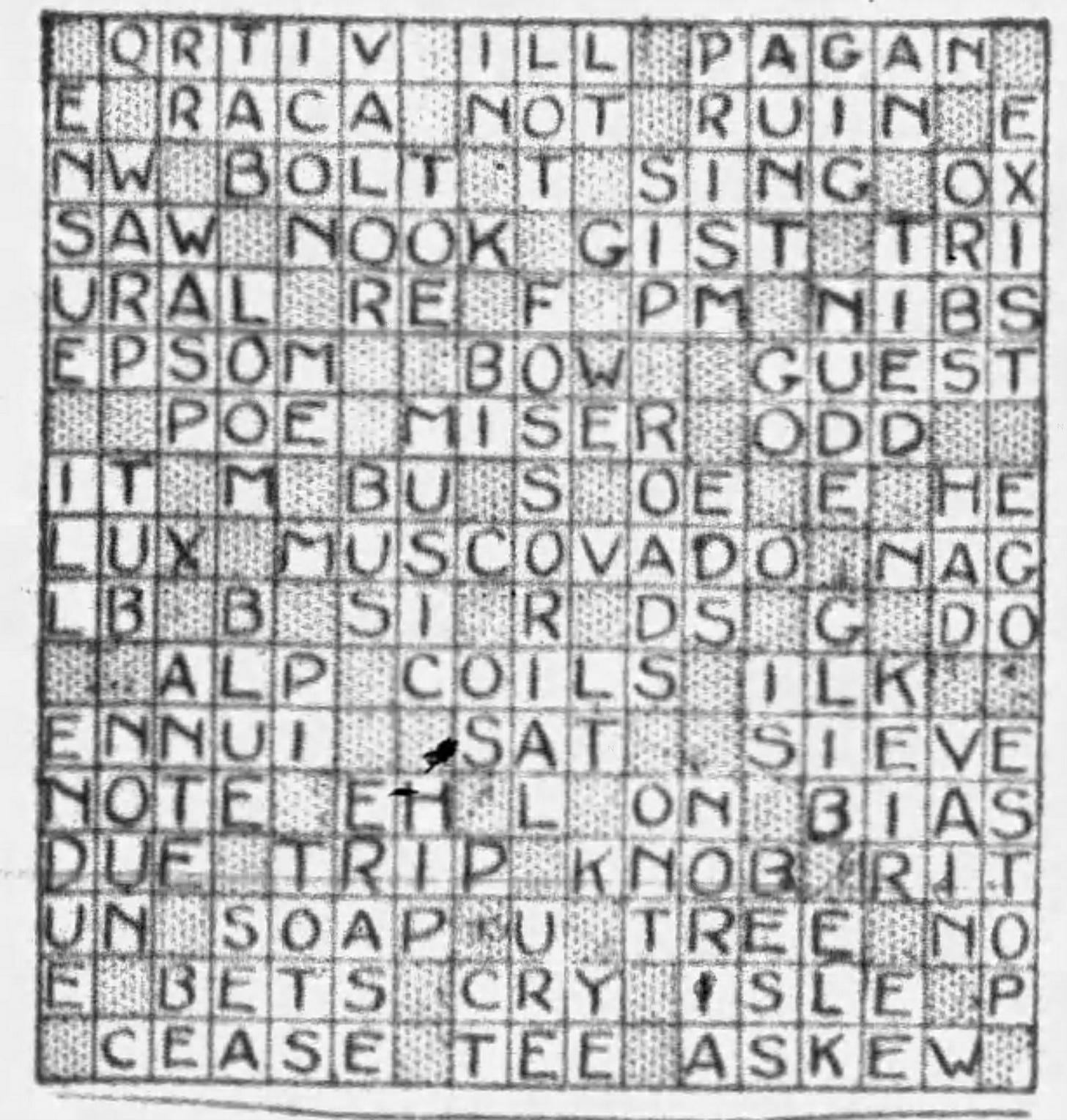

On the other hand, M.L. Johnson’s has to be the worst design of 1920. Johnson wanted the solver to write in most of the shaded boxes below—legibly—somehow.

Plus, answers included ORTIV and RACA—just in the first two lines!

Usage of crosswords or cross-words continued to hold the now-archaic meanings of “angry speech” and “acrostic puzzles.” In the June 30 Neodesha Daily Sun, it meant “a state of constant argument.”

It was through Joett Shouse that Hodges was put on the sub-committee. Shouse and Hodges are at cross-words. Shouse is a pal of Carter Glass, so just to heap coals of fire upon Hodges, he had Glass name Hodges on the sub-committee.

Arthur Wynne wasn’t quite “at cross-words” with the World. Its editors didn’t always fathom the appeal of the “silly squares,” but they understood the puzzle drove subscriptions and brought in syndication dollars. But behind the fun of FUN, Wynne was burnt out. After seven years, his interest in vetting new submissions was drying up: he now tended to approve most at a glance, without solving them.

That burnout seems the most likely reason for the hiatus of early 1920. Still loved by its fans, the crossword was entering a period of neglect by its caretakers.

And things would get worse before they got better.

Next week: 1921! And tomorrow: Adventures in layout.

The research that T Campbell has done/is doing into the history of crossword puzzles is

staggering and head-dizzying to consider. a-MAZE-ing. How does he find time to do

anything else? Watch John Wayne solve puzzles in the western TRUE GRID.