1921 was the year crossword editors just didn’t care.

It showed.

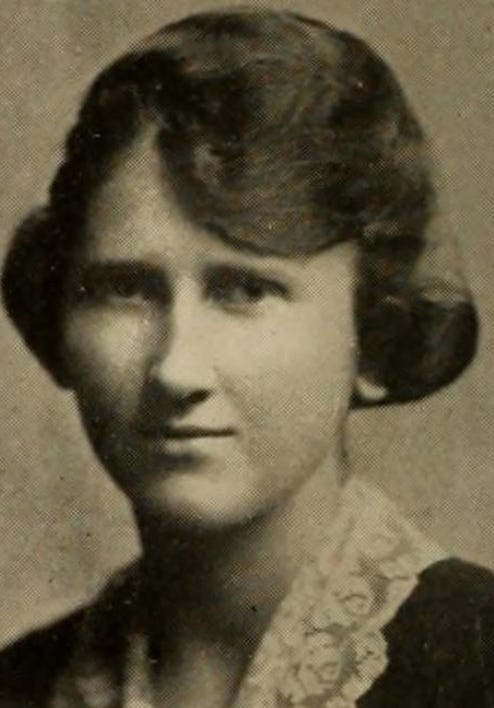

Arthur Wynne had invented the feature and encouraged readers to take it to further levels of creativity and amazement. Margaret Petherbridge, later Margaret Farrar, would become its brightest guiding light.

But that was Wynne’s past and Petherbridge’s future. Every hero has an origin story. Some begin as villains.

In 1921, a restless Wynne was ready to move on from the “silly squares.” They’d never given him the financial compensation he considered an inventor’s due, and he had other interests. Petherbridge, a secretary fresh out of college, became Wynne’s assistant, then successor.

A lifelong New Yorker, Petherbridge was a Renaissance woman well before she took the job. At Smith College, she’d been an actress, debater, and basketball player, and led a parade on horseback. Out of school, she’d organized college fundraisers and worked in a bank. But her real dream was writing, and she already had at least one story published—“A Bit of Irish Lace Which Failed to Adorn The Queen.”

Getting stuck with Wynne’s cast-off and its demanding readers was nowhere in her life plan. She’d never solved a crossword before taking the job—and she wasn’t going to start now. The burnt-out Wynne had been rubber-stamping the prettiest-looking grids without solving them for the last year or two. Petherbridge followed suit.

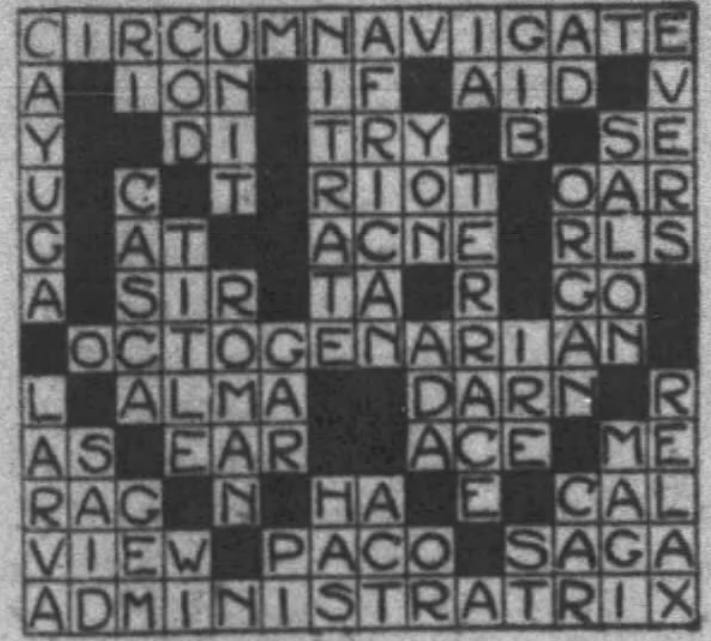

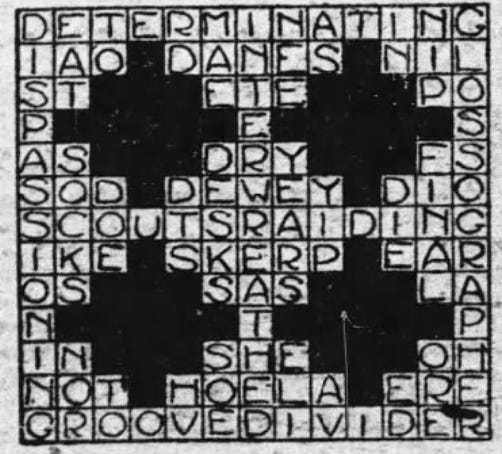

Wynne and Petherbridge’s disinterest didn’t quite smother the submissions’ creativity. The president-themed puzzle of the previous year got a sequel with fifteen presidential names in it (highlights added).

And some of those “pretty” grids were very pretty, rendering a 3-D house, a stylized eye, an Easter cross…and the New York World’s initials (which meant less if you were solving this syndicated in the Buffalo Courier Express).

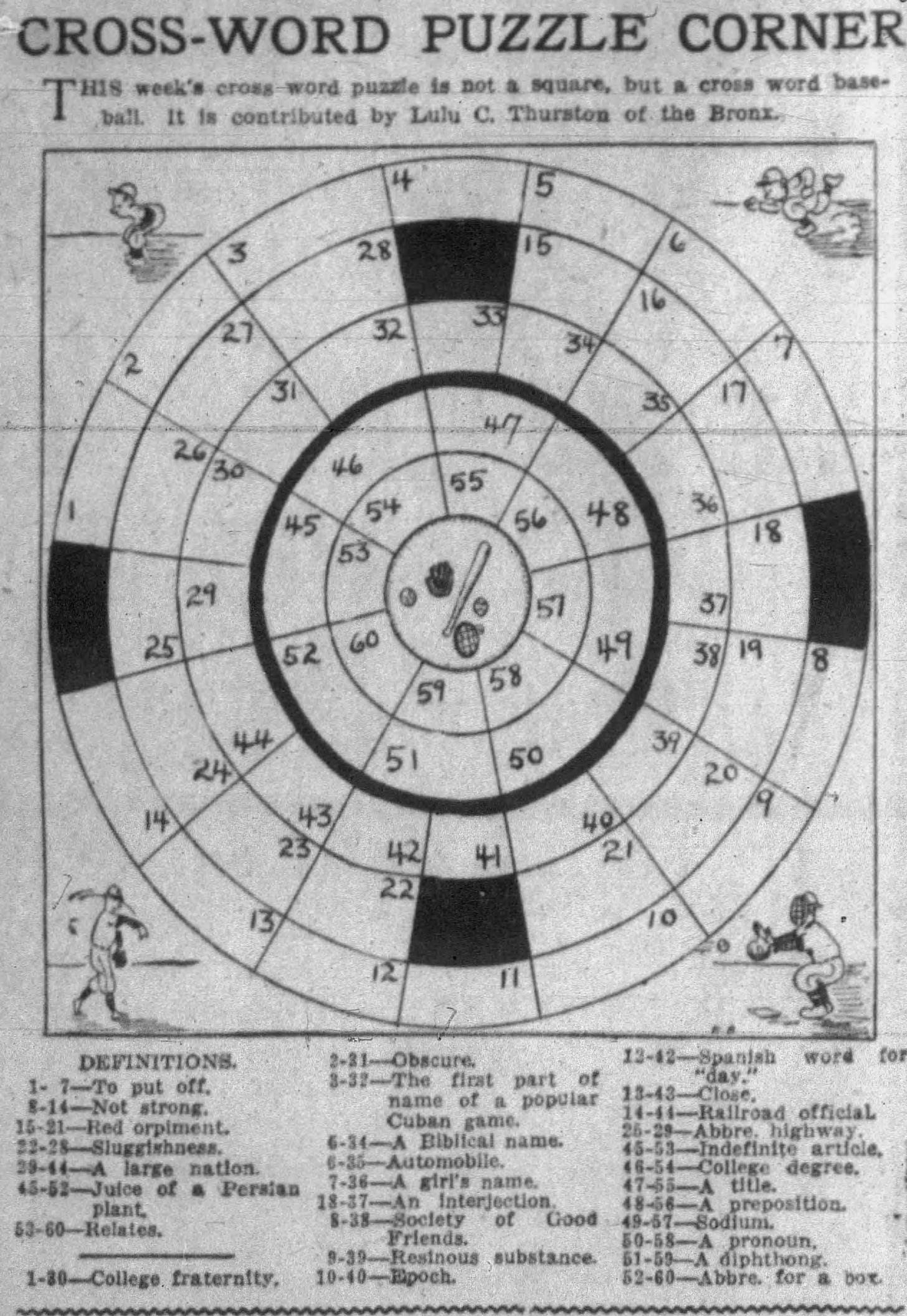

Also, Lulu C. Thurston offered up this circular “cross word baseball,” with a few cartoons enlivening the margins!

October 2’s World puzzle included BUTTERSCOTCH PIE, possibly the first “marquee” multi-word answer in a grid. (Other grids placed multiple words in a row, but as part of separate answers.)

However, just as many World grids of 1921 lacked ambition. Even by the relaxed standards of the day, it’s hard to imagine them gratifying solvers much.

(DECAPIPATE? Did someone decapitate the spirit of proper spelling?)

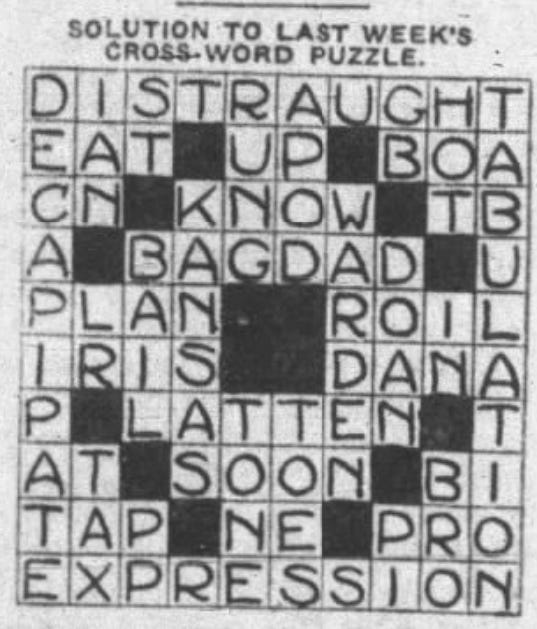

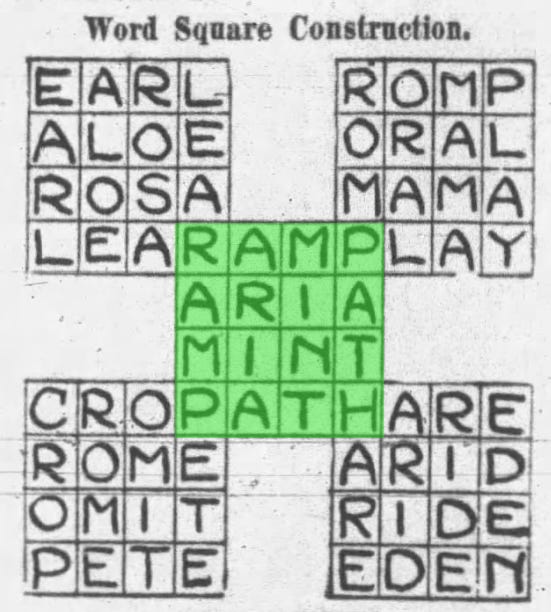

The World did offer more crossword-like puzzles. Overlapping word squares became a regular feature. (Coloring is added for clarity: the construction below is five word squares overlapping at the corners.)

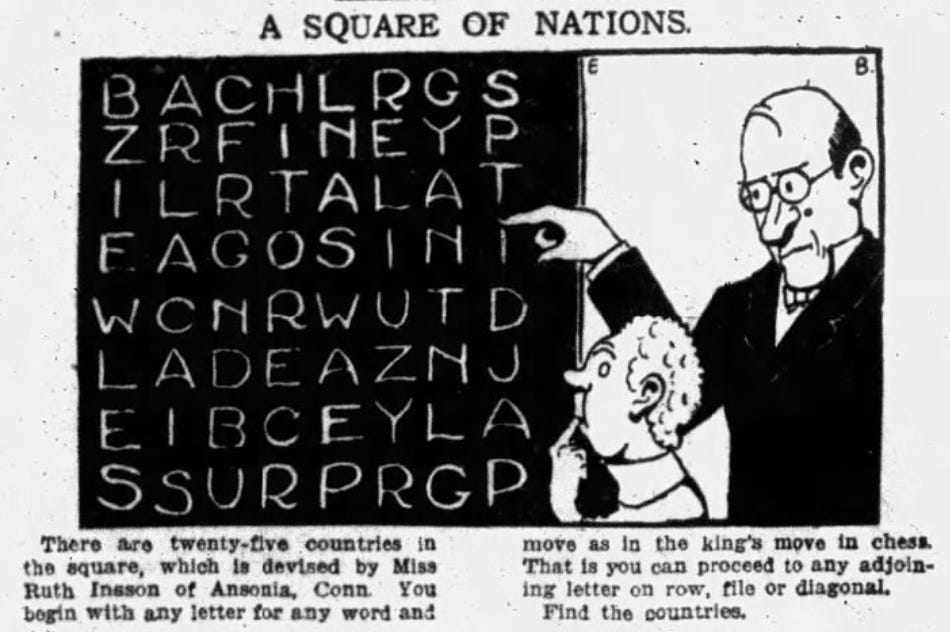

King’s-move and knight’s-move puzzles let solvers find words in them by moving from letter to letter in the style of those chess pieces.

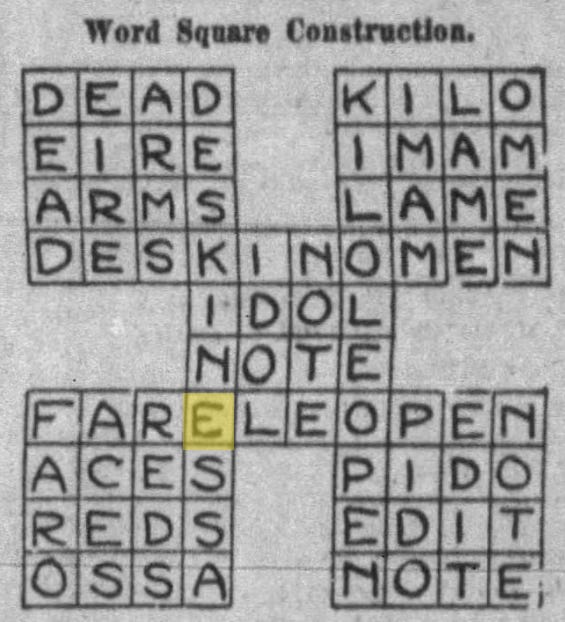

However, these other word-grids were not immune to the issues plaguing the crossword proper. Here’s a word-square answer key with an E that should be an O:

That’s an easy fix, but by Petherbridge’s own later admission, some puzzles had issues that rendered them unsolvable.

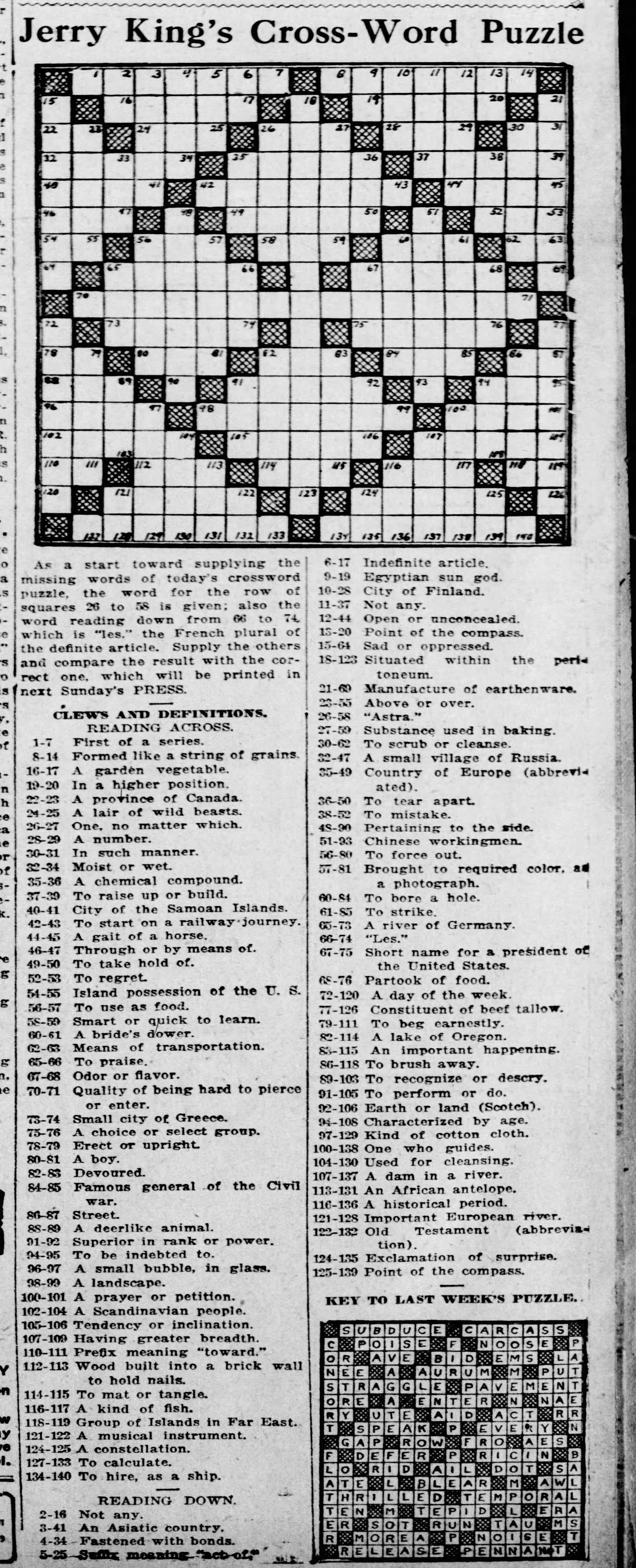

“Jerry King’s Crossword” soldiered on, more reliable than the World but not without its eccentricities. The puzzle below gives two answers in the clues—ASTRA and LES. (The World could publish such “gimmes” now and then too.)

Despite its quality issues, the crossword’s pop-culture footprint was growing. A profile of the cartoonist Clare Briggs from the March 4 Atlanta Journal includes his struggles with a crossword:

“I haven’t got it yet,” admitted Mr. Briggs. “They say Roosevelt had a vocabulary of 125,000 words, or maybe 25,000. Anyway, he’d have needed all of them to work that sort of stuff. ‘Otic,’ for instance. Ever heard of ‘otic’? Neither did I, until I had to dig it up to fit the definition. ‘Situated near to, or pertaining to, the ear.’ Sounds like the rear end of a word: the caboose, maybe.”

A profile of the National Puzzlers’ League by Prosper Buranelli (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 20) labeled the crossword a gateway drug to more advanced wordplay: “How do people become puzzlers? Through the crossword puzzle.”

Briggs and the NPL would both reenter the crossword’s story in later years, Briggs offering multiple tribute cartoons, the NPL a contribution…then, later, jealous condemnation.

This joke from the March 27 Gasconade County Republican indicates a local market for crossword collections, a few years before that became a thriving publishing genre:

Clerk: Would you like one of our cross-word puzzle books? They are great to improve your vocabulary.

Woman Shopper: We haven’t any to improve. Only a dining room and a parlor.

“Rural Editors Paragraphs” ran the following one-liner:

Speakin’ of crossword puzzles, Steve Trotter says his wife is about the crossest word puzzle he ever came across.

“Ha ha, women, right, fellas? They do words bad. And they’re always mad, no matter how many times we insult them! Truly, they are nature’s greatest mystery.”

The early 1920s were a weighted time for women, who had only just gotten the vote in 1919. The pressure was pronounced for intelligent women to prove themselves, which was one reason Petherbridge resented her assignment. Soon she would come to see editing the crossword as less of an obstacle and more of an opportunity.

But she wouldn’t come to this conclusion alone. An obnoxious poet would enter the picture first. And the crossword’s story would end up hitting some of the beats of a romantic comedy.

Next: The Journal of Wordplay final prep!