Before we begin, a minor content warning—this roundup includes a few notes on a shape people find upsetting in a modern context. If you’d prefer to skip that part, just stop reading after the words “And…well…” and come back to tomorrow’s installment.

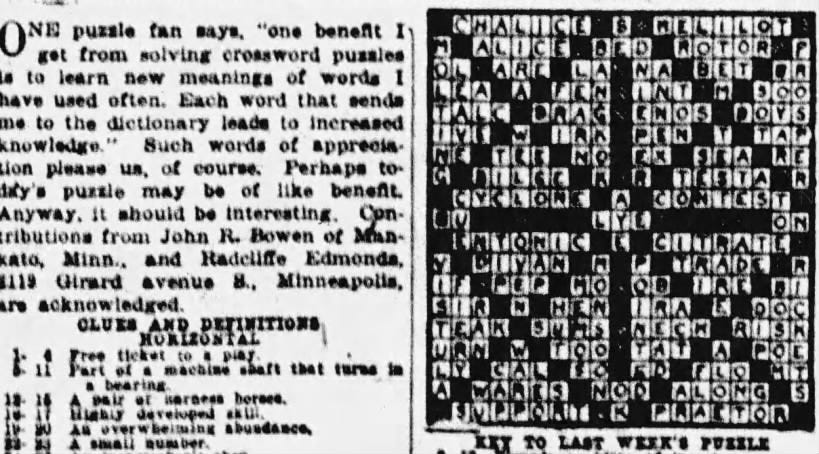

As the year began, Jerry King’s Crossword Feature was attempting the warmth and humor Petherbridge was showing in the World.

Howard Marshall, who contributes today's puzzle, seems to specialize in literature, judging from the number of author's names used…

Miss Olga Elstner, a puzzle friend, composed today’s interesting crossword puzzle…

It was hopelessly outclassed. As an editor, Petherbridge was already sharp; as a commentator, she was unstoppable.

We were almost through verifying a good-looking puzzle when we bumped into one of those obsolete words and promptly tossed the whole thing away. Then this one by Walter B. Goodman happened along and restored our trust in contributors…

The following puzzle is by James Street. That’s his name, not his residence…

[The crossword:] To be taken continuously Sunday morning, until completely dissolved. This is sure to be good for what ails you…

We hope our customers will like this one by Thomas Sayre. We are worried, however. If you all continue to get so much pleasure out of it, there will soon be a blue law against solving Cross Words on Sunday.

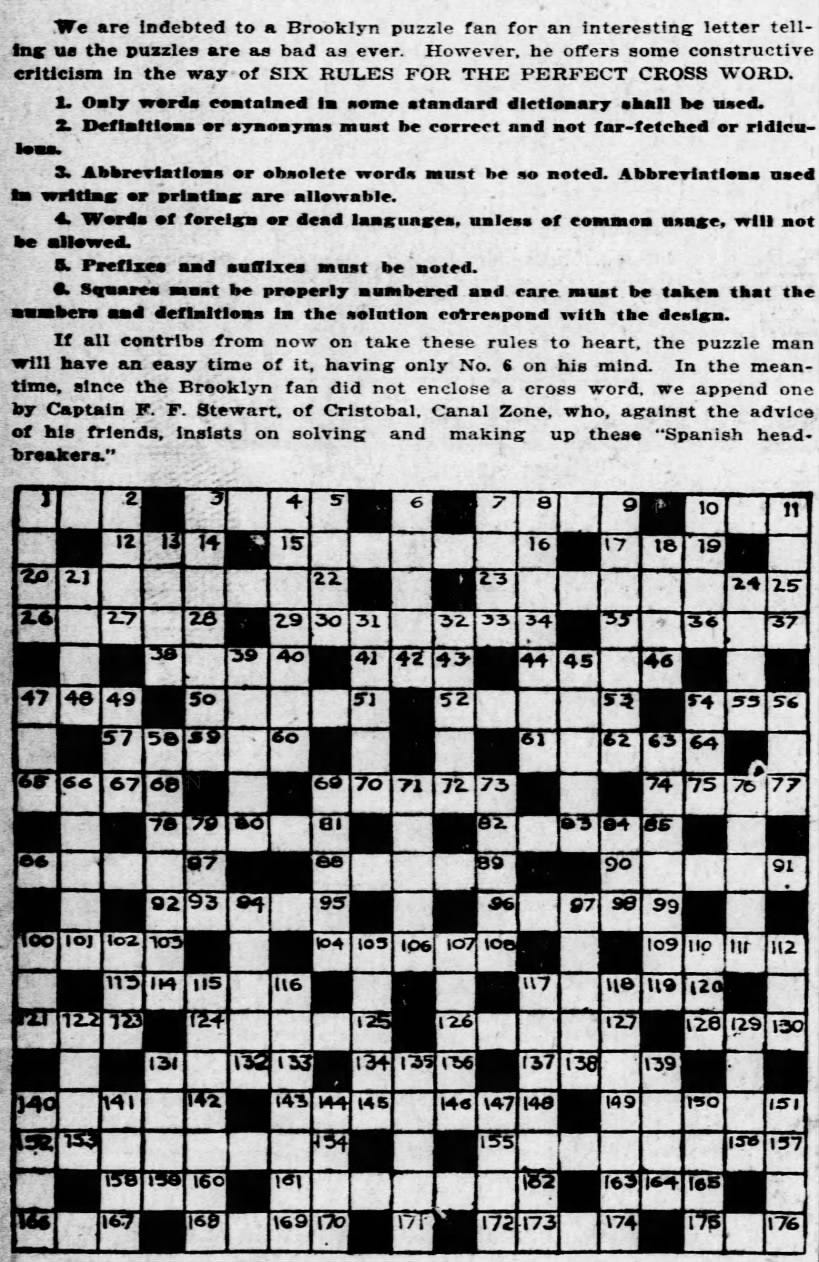

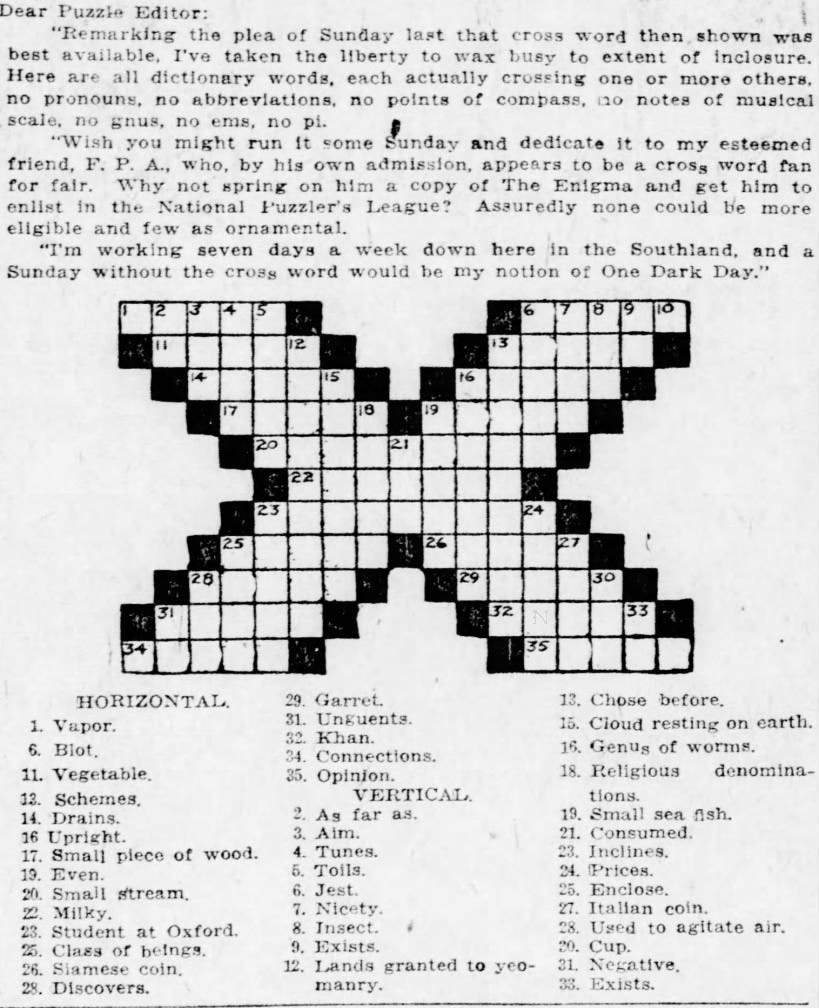

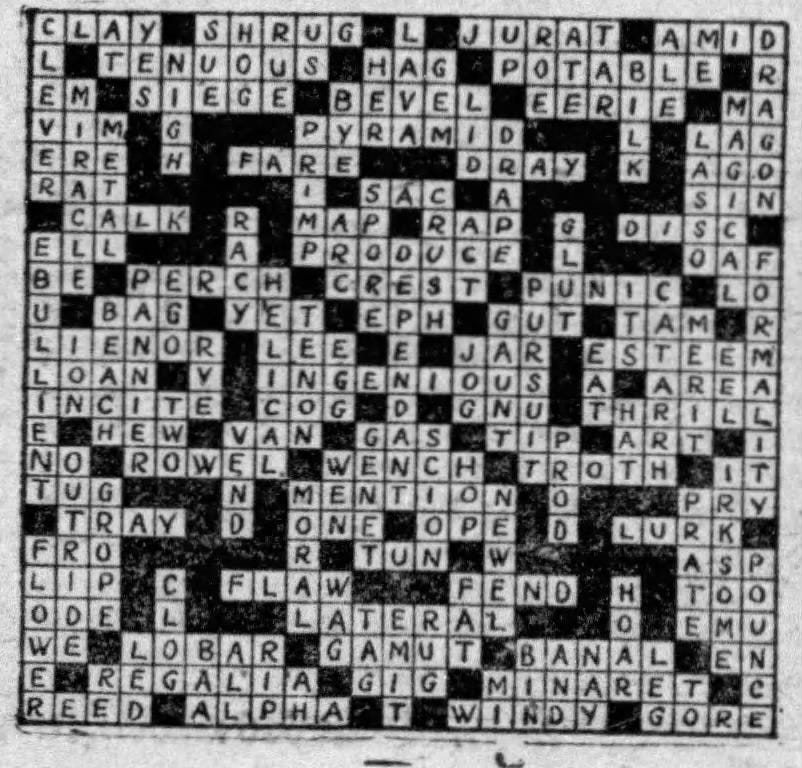

Petherbridge let “contribs” write their own intros now and then. One such was “Enigma,” a representative of the National Puzzler’s League with an ulterior motive. Despite the unchecked and two-letter words at the corners, this construction feels close to modern standards and was the most “open” grid to date.

Sometimes Petherbridge published puzzles she didn’t 100% endorse, pointing to their flaws to inform the next wave of contributions. Of the following grid, she wrote,

Its principal defect is that it doesn’t follow the rule providing that every other letter of a word shall be keyed up with some other word. This would make it possible for you to get all the horizontal words and yet not all of the vertical—which is dissatisfying, to say the least.

In March, the World published its first celebrity constructor, Gelett Burgess, best known today as the author of 1891’s “The Purple Cow”:

I never saw a Purple Cow,

I never hope to see one;

But I can tell you, anyhow,

I'd rather see than be one.

Mystery novelist and poet Carolyn Wells was published in May, just after a second Burgess work. She would publish a crossword book of her own the following year.

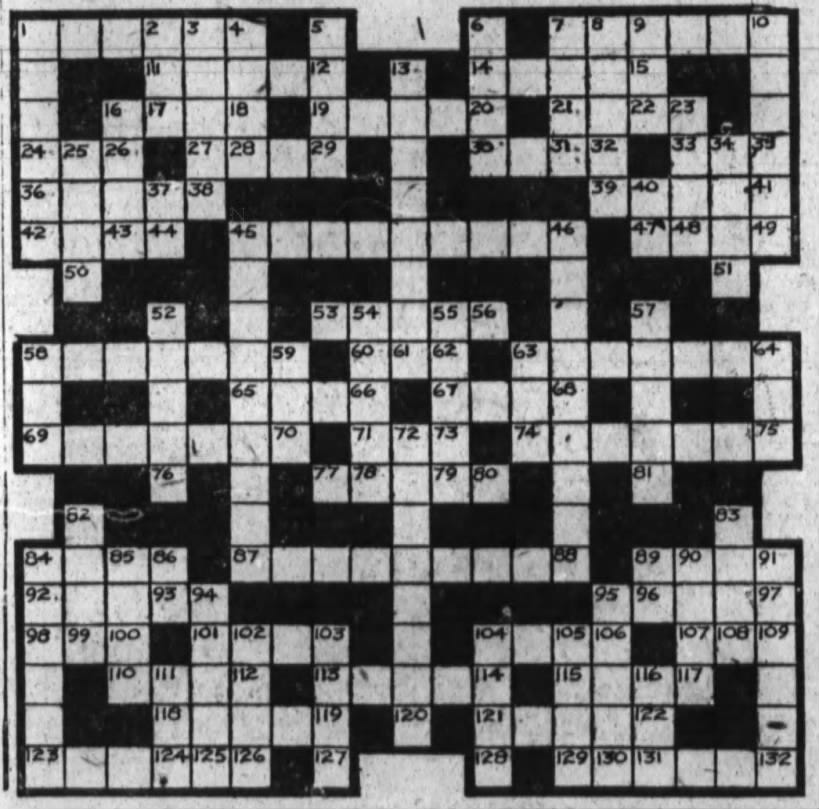

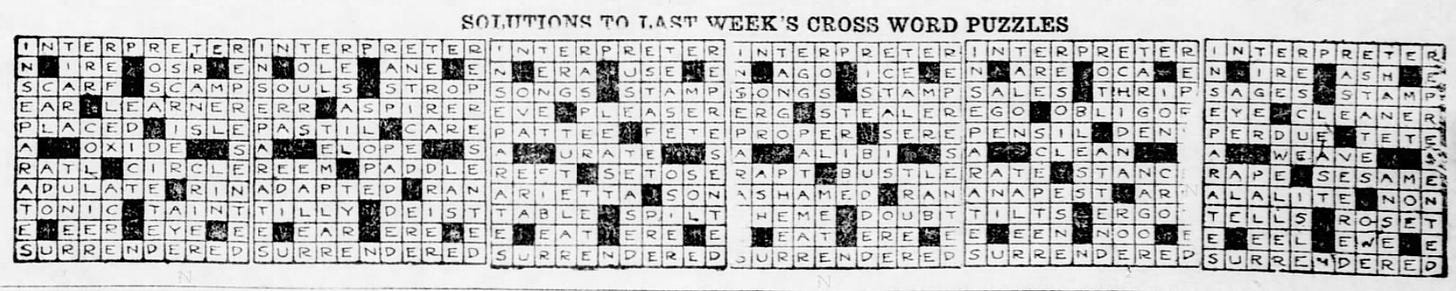

Other World novelties of 1923 included super-sized puzzles, a puzzle themed around the recent discovery of King Tut’s tomb, an extra-hard pre-filled grid for which solvers had to write clues, and a set of interrelated answers (all working off the same grid design and four longest answers).

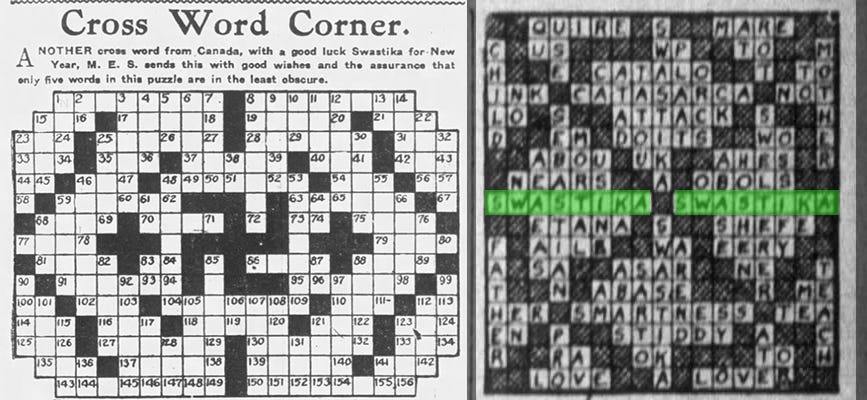

And…well…

It had appeared in crossword design before, but 1923 really seemed to be the peak of the swastika’s popularity. (Forever, let’s hope.) It was then still seen as a merry symbol of good luck, and the World and Jerry King crosswords both greeted the new year with it—the World with a central design and King with a duplicated central entry. The Boston Globe showed an original four-swastika crossword on August 5.

All these came before the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, the Nazis’ first attempted rise to power. But the attempt was seen as an embarrassing failure at the time, so even that didn’t taint the symbol too much: another such design appeared in the following year’s Cross Word Puzzle Book. 1923 may have been the peak of its nonpolitical usage, but such usage took a while longer to die out altogether.

All was not clear sailing for the World. Syndicators like the Buffalo Courier Express dropped it for the inferior but more predictable Jerry King feature, and The Boston Globe became a real competitor.

More about that tomorrow!