On March 18, the Globe was still recycling puzzles that had appeared in the World two years earlier. But on May 27, it became the first major venue to offer non-Sunday crosswords, adding Saturdays. The Globe advertised this move in its own paper and others, using it as a major circulation-builder.

The Saturday Globe developed its own style of commentary, addressing multiple letter-writers and submitters per week, including rejection notices, and even teasing approved contributors like Chet Bent:

I am afraid Miss L.C. of Peterboro is going to disapprove of you, “Chet.” F’instance, she thinks it more fair, and I fear more erudite, to define “mare” more literally than as just as “a horse.” From a strictly educational point of view she is right, no doubt, but we have considered the cross-word puzzle as a sort of delightful game and allowed some brainteasers to form part of the definitions. If the definitions are too hard and the fun too elusive, we want to know, of course.

Dr. H.A. sent us a puzzle that was not interlocking throughout: in fact it consisted of 12 little puzzles very exclusive and much to themselves. This type of puzzle is not approved of by the majority of fans, for evident reasons. It is not hard enough. Try again, H.A., and mix them up, for as you say, it is fun.

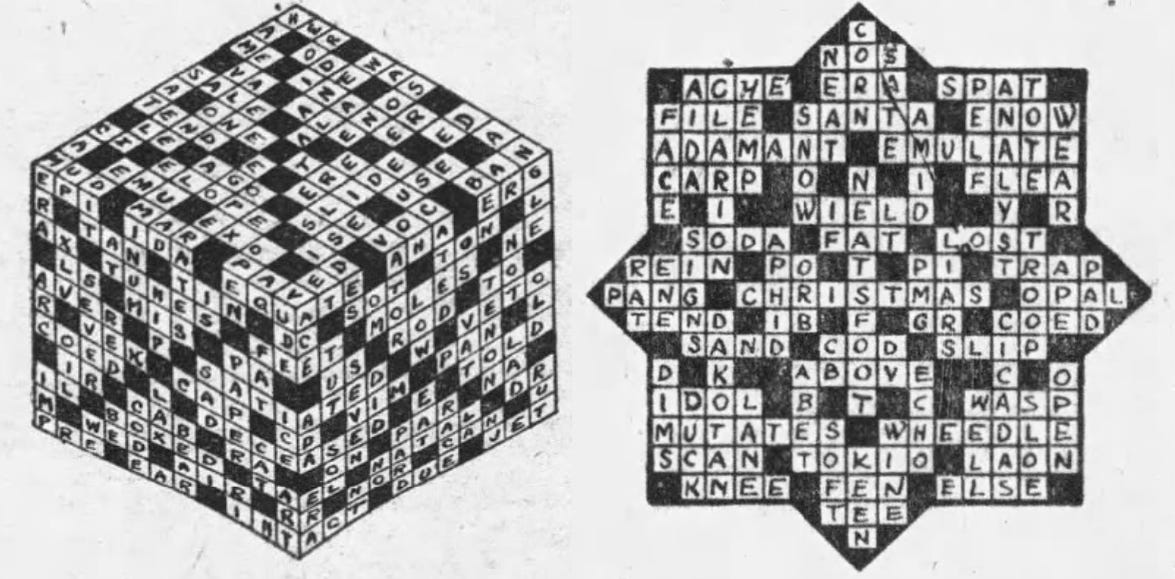

At year’s end, the Globe offered up a cubic crossword and a Christmas star, the latter with a set of poetic clues.

Here’s how it clued SANTA:

He comes in the night, one night in the year,

Silent and stealthy, yet bringing no fear;

Though mortals ne'er see him, return of glad day

Brings proof of his presence. Oh, Lookit! Hooray!

The Globe promised its puzzles of 1924 would be better than its puzzles of 1923—a promise it seemed more than capable of keeping.

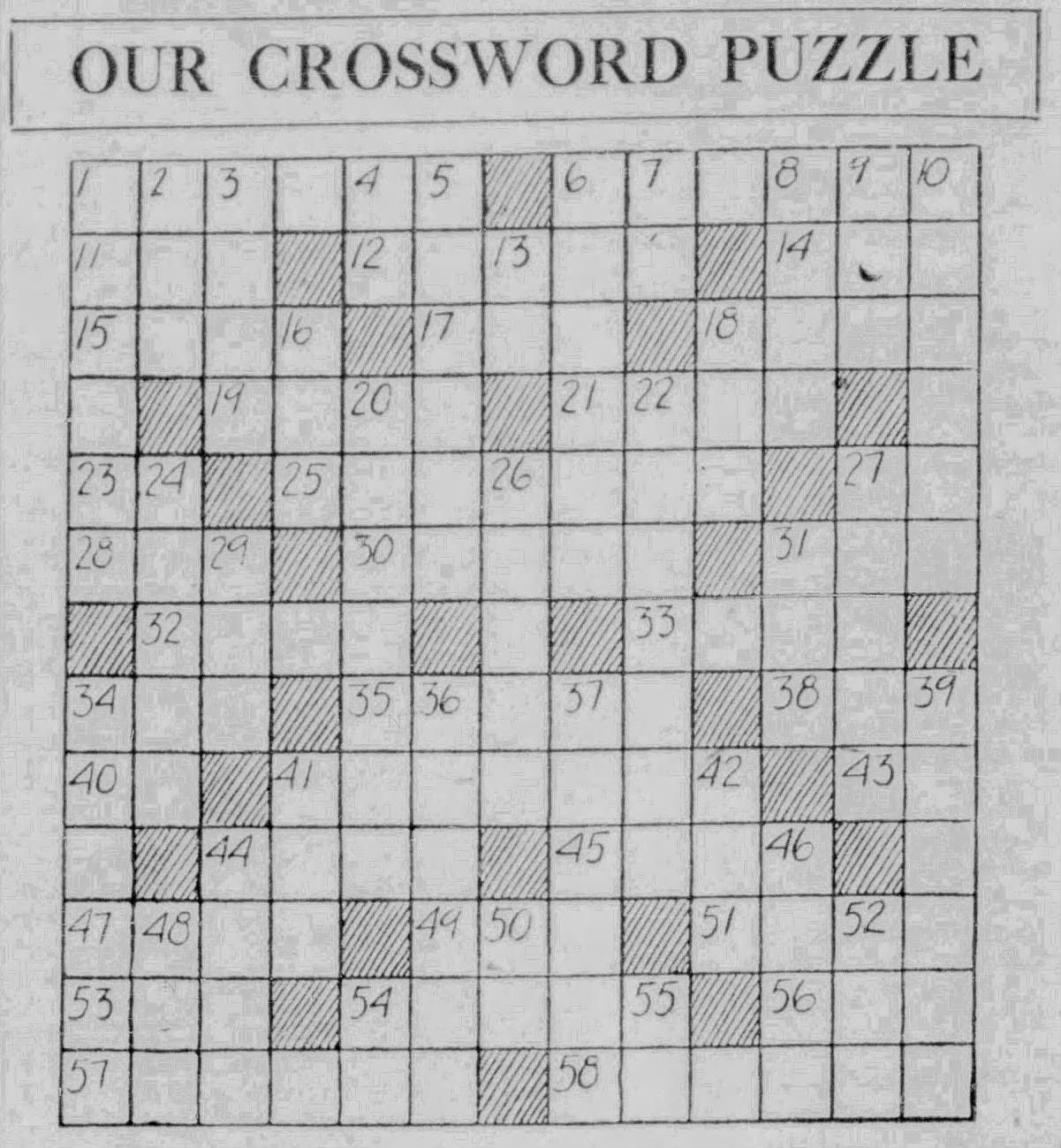

Venues beyond the Globe, the World, and Jerry King continued to proliferate. One of them was The Lloydminster Times, an eight-page Canadian weekly with the first known crossword to use the modern numbering system. No end numbers on this grid!

We don’t know just when The Lloydminster Times began its feature. This sample is taken from the oldest issue currently in digital records—July 1, 1923—but that issue contains answers for an earlier puzzle, so it must have gone back at least as far as June. (The front cover lists the July 1 edition as “Vol. XXI, No. 1052,” so the whole publication is much older than that.)

The World instituted this same numbering system at the suggestion of the contributor “Radical,” introducing it on July 22. The grid below may not have been first to simplify numbering, but it was the most influential: other World puzzles and competitors soon followed suit.

The puzzle proliferation was unsurprising. Crosswords were good for business. Usually. Except for that one company that crossworded itself out of existence.

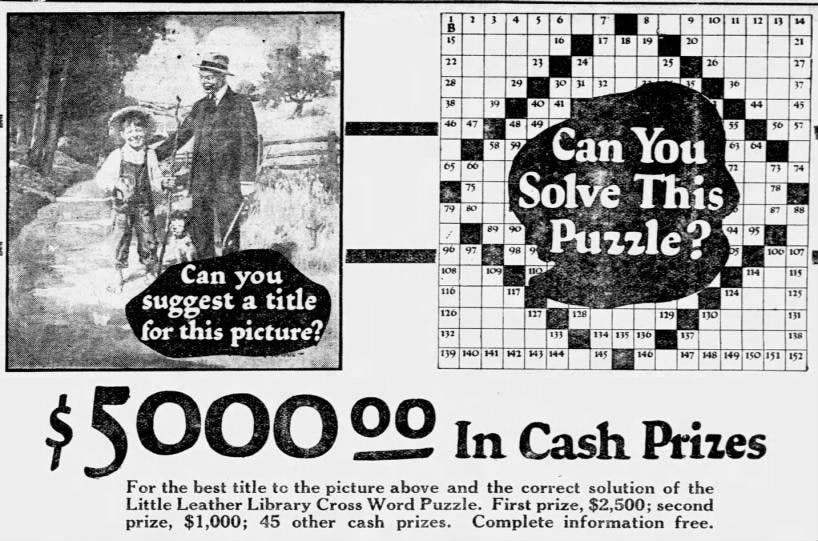

On July 1, a crossword and photo-captioning contest offered $5,000 in prizes—a formidable sum in 1923—”to encourage the reading of good books--in particular, certain masterpieces contained in a new set of thirty volumes just published by the Little Leather Library Corporation.”

The publisher had done well with its small-scale leather-bound volumes, and this contest earned some publicity (the winner was Amelia E. Clark of Bennington, Vermont). But it didn’t seem to work out. Robert K. Haas Inc. bought the company out the following year and shut it down one year later.

Perhaps there was too much competition for attention. The crossword was going international—publications in Australia and Russia had picked it up, and the UK’s prime minister Stanley Baldwin was among its fans.

But those fans hadn’t seen anything yet. Petherbridge was already working on something else, something that’d change the face of puzzling—and publishing—forever. More on that, coming this Thursday.

The 3D crossword is giving me war flashbacks to Ricky Cruz's present-themed puzzle from Lollapuzzoola '23, where half the competitors left something like 19 squares blank by mistake :P It's a fun idea for a grid though. Surprised more people haven't tried to make it a thing!