This was the year things got really nuts.

These four posts will run long—they just have to—and still won’t be long enough. For fuller accounts, I recommend Anna Shechtman’s The Riddles of the Sphinx and Ben Zimmer’s Crossword Craze. I’ll be referencing both in more detail. But I disagree with Zimmer on one point.

Zimmer places the “crossword craze’s” beginning on April 10, 1924, with the publication of the Cross Word Puzzle Book. But even in the year’s first few months, more and more newspapers were adding crosswords, citing their addictive power and the rise of “cross-word puzzle clubs.”

On January 16, The Palisade Times praised the crossword as “a sensible fad…gaining in popularity all the time” and followed up with the February 20 observation, “Just when we got autos and balloon tires to get us away from home, here comes the radio and cross-word puzzle to keep us there.”

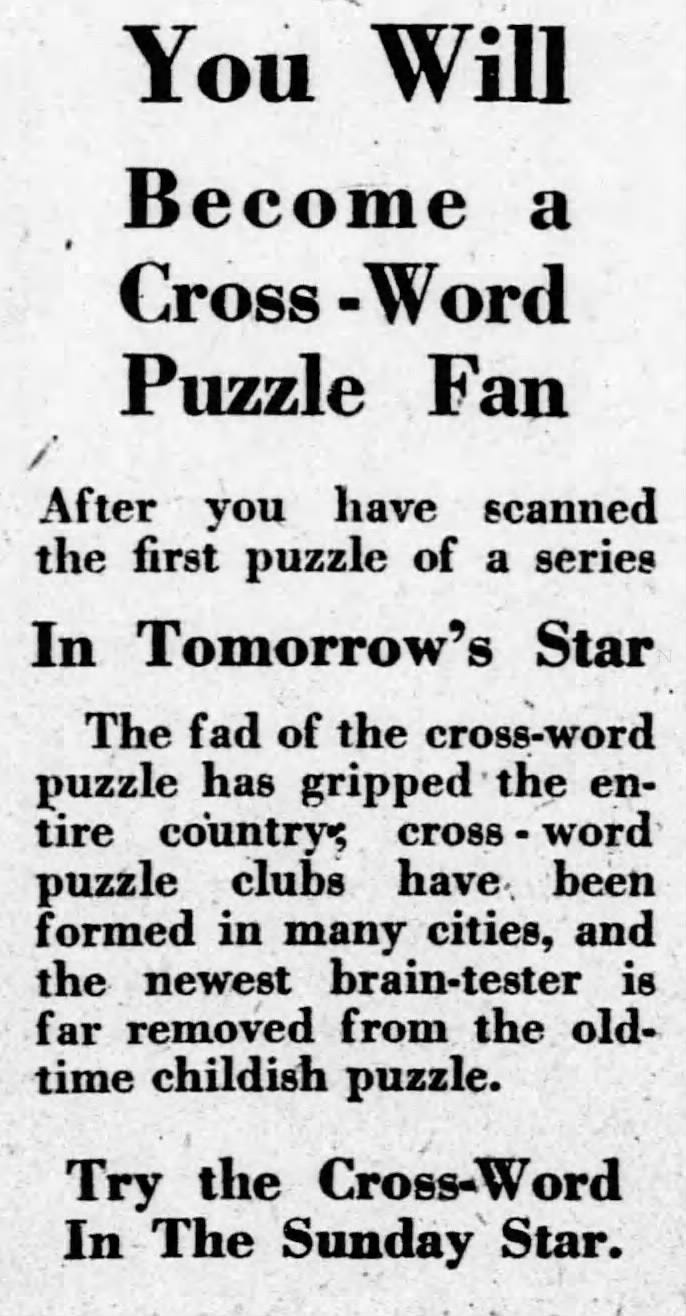

“You Will Become a Cross-Word Puzzle Fan,” The Evening Star screamed at its readership, hawking the February debut of its feature on its front page.

(“Your Fandom Is Inevitable! Free Will Is an Illusion! SURRENDER TO THE GRID”)

But maybe Zimmer and I are just arguing semantics. Because we do agree on this: on April 9, the crossword had greater heights yet to reach. And when The Cross Word Puzzle Book did hit shelves the next day…it hit them with a thunderclap.

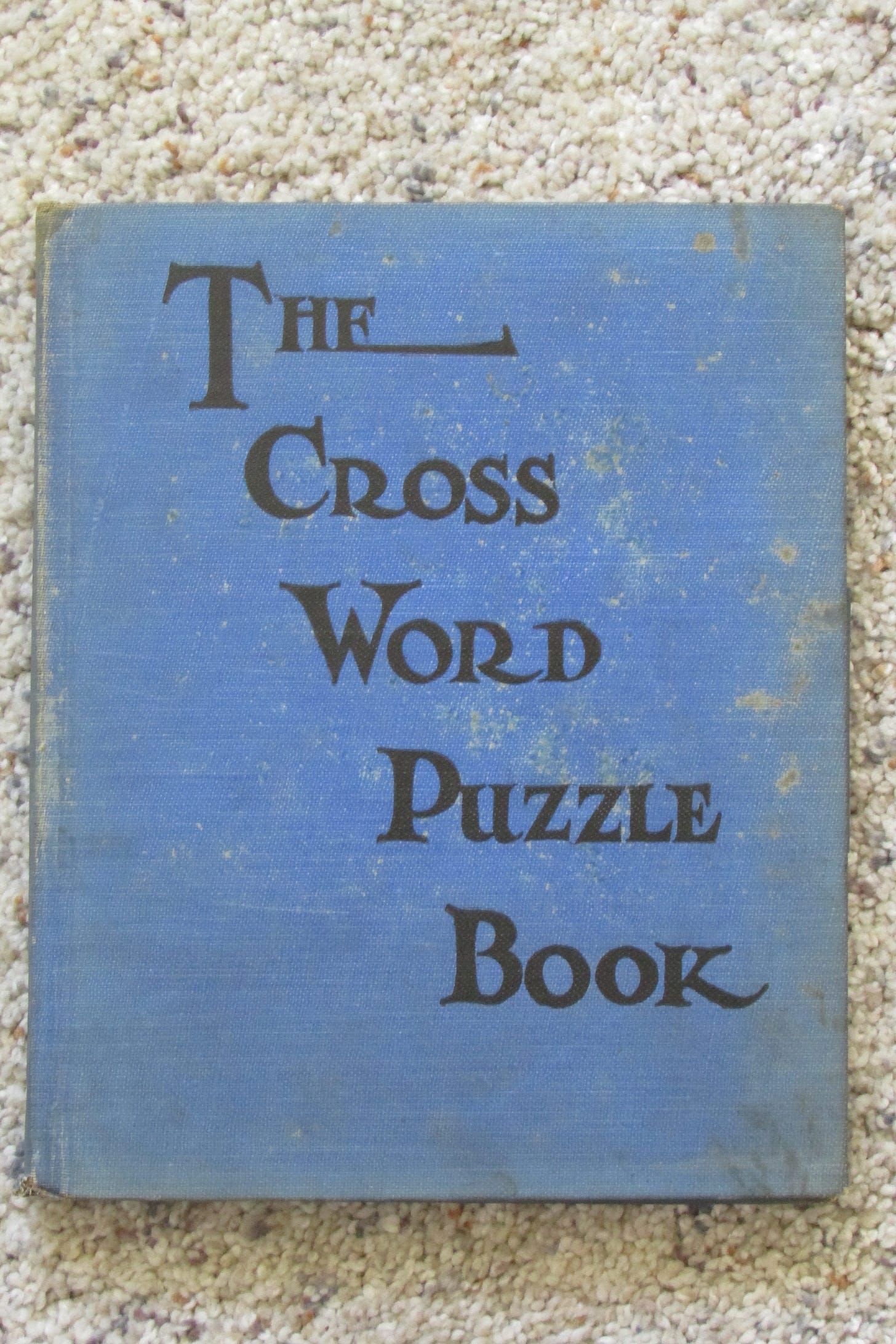

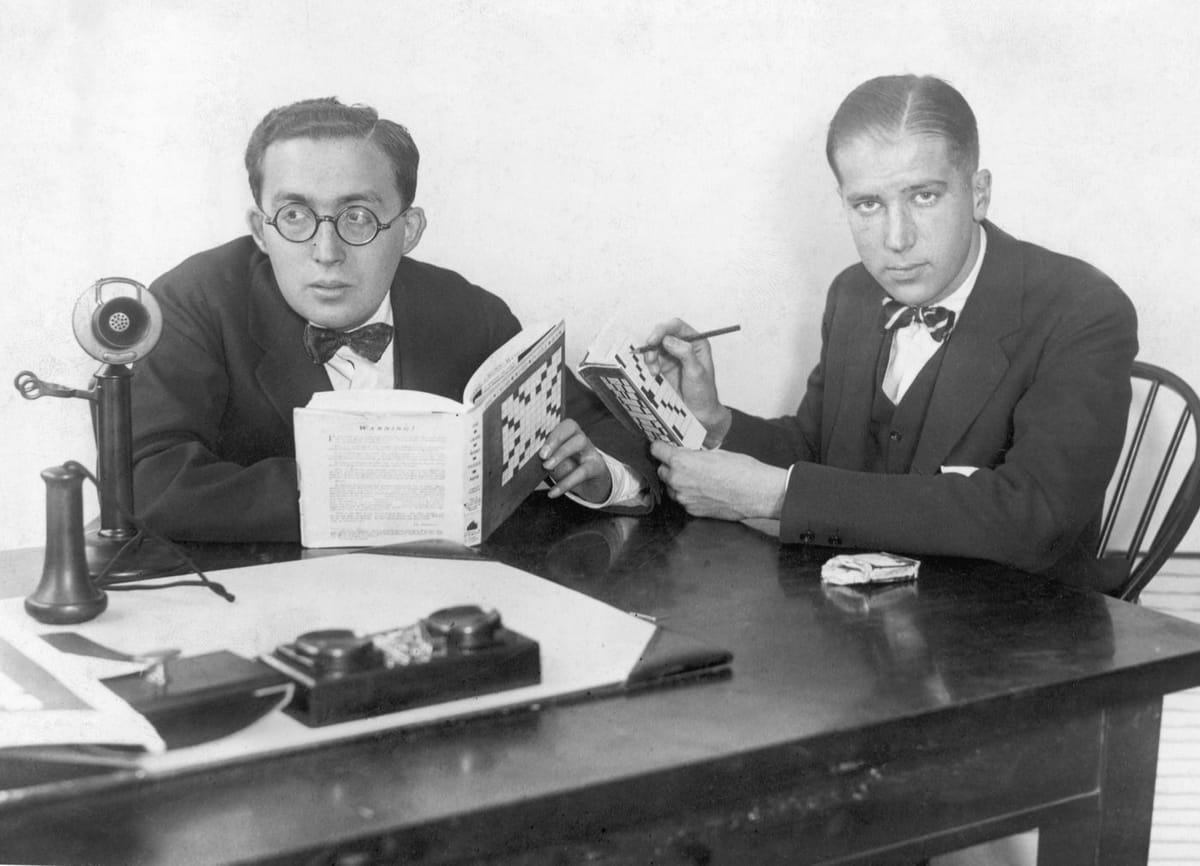

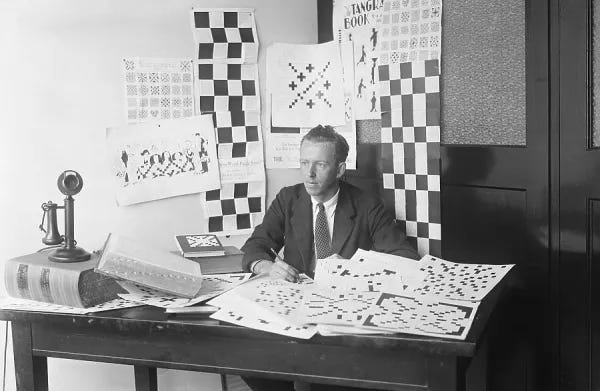

Richard L. Simon had been a sugar importer and piano salesman before meeting trade magazine editor M. Lincoln Schuster. Founding the “Plaza Publishing Company” to test the waters for a crossword collection, they printed a tentative 3,600 copies and left their names off it. (Note the book’s original paper cover in the picture below.)

Success cured this modesty within hours. The second, third, and fourth volumes—all put out that year—bore Simon and Schuster’s name. The volumes dominated four of the five top slots for nonfiction that October.

In a single day in December, they sold almost 150,000 copies, and by the end of the year, they had sold half a million.

—Anna Shechtman, The Riddles of the Sphinx

Simon and Schuster weren’t the only ones emerging from anonymity. Margaret Petherbridge came out as New York World crossword editor, dropping her earlier “he/him” and “Ye Ed.” disguises. Her roles as book and World editor were symbiotic. Crossword Puzzle Book volumes pulled material, with permission, from the World’s slush pile.

Petherbridge didn’t take center stage, though. Though her foreword came first, her name came third in the Cross Word Puzzle Books’ title pages and would for years afterward, behind two other World editors who worked with her on the books, both of whom would try to achieve even greater prominence a year later.

No one knows who decided to credit Petherbridge third. Everyone was a little skittish about the marketplace they were entering. Would it minimize risk to have two male names before the female name on the cover? Such thoughts could have come from the risk-averse Simon and Schuster, the credit-hungry co-editors, the self-effacing Petherbridge herself, or some combination.

However, it seems probable Petherbridge’s co-editors did more than just collect unearned accolades, at least on the earliest books. The workload called for all hands. In 1923, Petherbridge published her edits of about 60 puzzles; in 1924, “Team Petherbridge” published closer to 300. Two hundred of those came from the books, but the World was also stepping up its crossword output: by year’s end, it was running three or four on Sunday, one every weekday and Saturday.

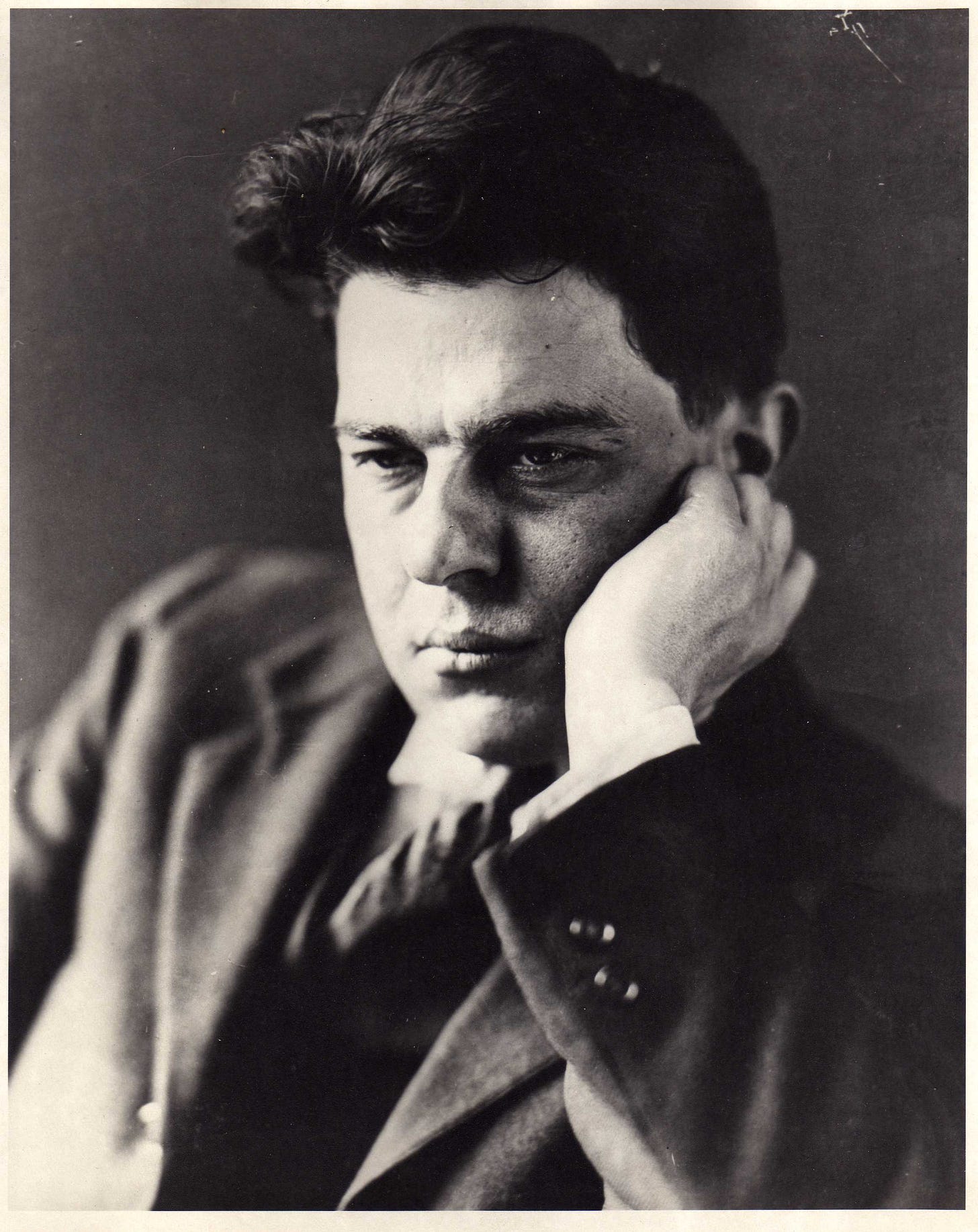

And those co-editors were no intellectual lightweights. Prosper Buranelli was a polymath and walking encyclopedia who “looked like an unmade bed”: later that decade, he’d begin working with writer and explorer Lowell Thomas on film and newsreels. He’d play a role in the development of Cinerama and early television.

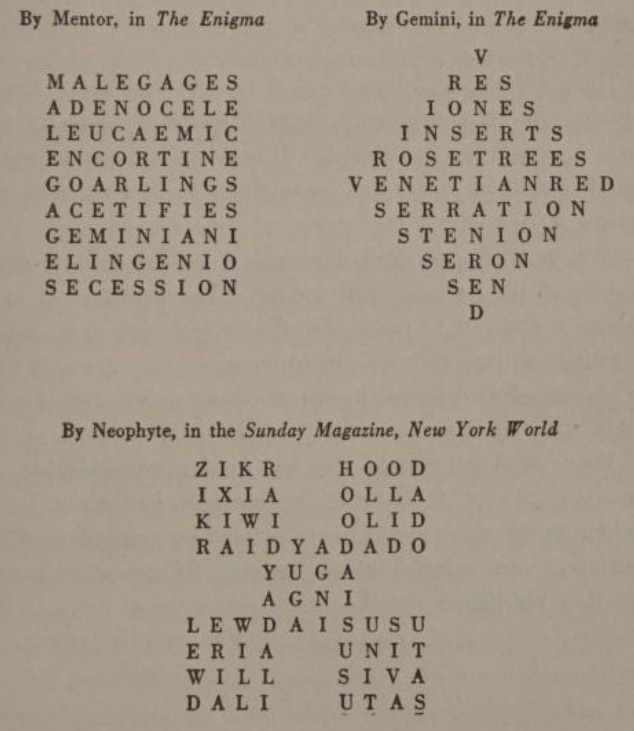

His foreword placed crosswords within a heritage including the Sphinx’s riddle and rebus-like Mayan hieroglyphics. Buranelli also recognized the “recondite ingenuities” of the National Puzzler’s League—word squares, word diamonds, and such.

Less is known about F. Gregory Hartswick, whom Buranelli once called an “office bug.” Hartswick’s writings included cosmopolitan pieces for those curious about the world (“Bohemia Table d’Hote,” “A Chinese Marvel”) and advice (“If I Wanted To Be Sure of an Income at Sixty,” “If I Wanted to Protect Myself Against Sickness”). He took to the crossword gig, and in the first volume, he showed his cognitive chops:

There is the pure esthetic stimulation of looking at the pattern with its neat black and white squares, like a floor in a cathedral or a hotel bathroom; there is the challenge of the definitions, titillating the combative ganglion that lurks in all of us; there is the tantalizing elusiveness of the one little word that will satisfactorily fill a space and give clues to others that we know not of; and there is the thrill of triumph as the right word is found, fitted, and its attendant branches and roots spring into being.

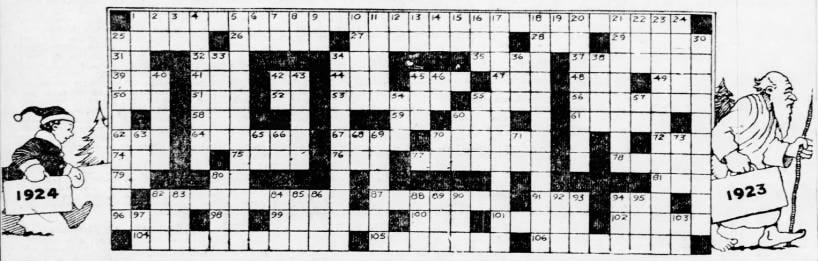

Petherbridge, Buranelli, and Hartswick were trying their hands at construction, too, just to keep from getting bored. We don’t know which if any 1924 puzzles were Petherbridge’s (many ran with no byline or with obvious pseudonyms). She did publish a Buranelli-Hartswick collaboration as a World New Year’s puzzle, adding this poem: “To honor Nineteen Twenty Four, this puzzle was assembled. Two experts burned the midnight oil, the dictionary trembled.”

Another two-editor collaboration ran as “A Duet” in the second Cross Word Puzzle Book, though the editors would not reveal which two had gone out to lunch and come back with a puzzle design. It wouldn’t be their only productive lunch date—but later for that.

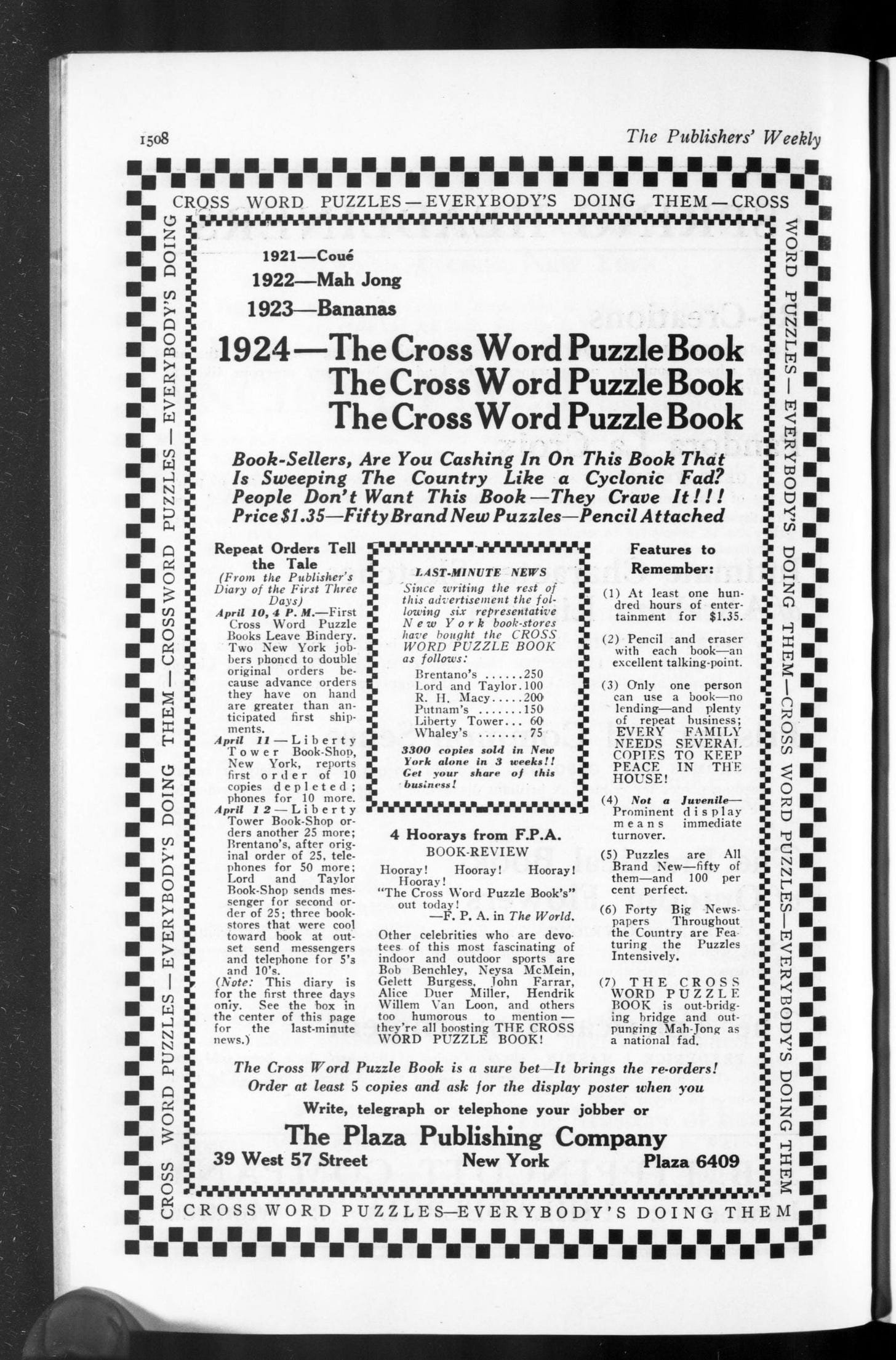

Simon and Schuster acted fast to cement their success. As Zimmer notes, this ad in Publisher’s Weekly hyped the book as a can’t-miss opportunity:

Features to Remember:

(1) At least one hundred hours of entertainment for $1.35.

(2) Pencil and eraser with each book—an excellent talking point.

(3) Only one person can use a book—no lending—and plenty of repeat business: EVERY FAMILY NEEDS SEVERAL COPIES TO KEEP PEACE IN THE HOUSE!

(4) Not a Juvenile—Prominent display means immediate turnover.

(5) Puzzles are All Brand New—fifty of them—and 100 per cent perfect.

(6) Forty Big Newspapers Throughout the Country are Featuring the Puzzles Intensively.

(7) THE CROSS WORD PUZZLE BOOK is out-bridging bridge and out-punging Mah-Jong as a national fad.

“No lending!”

Simon sold books the way he’d sold pianos: like his next meal depended on it. He and Schuster would often spend five or ten times as much on marketing as their competitors. They had a vision for their future and their industry’s. That vision went far beyond puzzle-peddling, a fact they’d make clear soon enough.

But the Cross Word Puzzle Book series would become the longest-running book series ever published. The crossword was something one usually filled in and threw away, and the craze would be short-lived. Crazes always are. But Petherbridge and company were building a brand, and building it to last.

Next: The advancement of the art.