Margaret Petherbridge could’ve rested on her laurels in 1924. She was getting more money and more respect, and the nation had gone bananas for an art form she knew better than anyone. But there was still room for improvement. “Can’t please everybody,” she’d shrug, but she was still game to try.

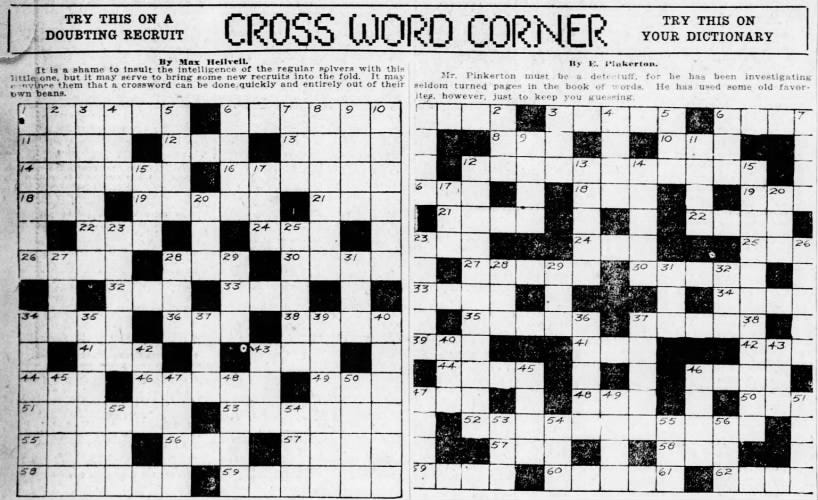

One of her experiments involved publishing two puzzles side-by-side—one for beginners, one for experts.

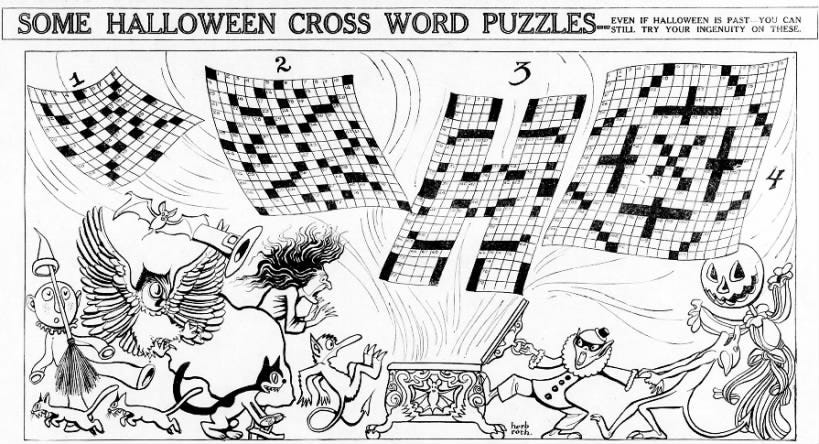

By year’s end, crossword fever had grown so hot that four grids weren’t uncommon, crowding out the anagram and word-find puzzles that had kept it company in the puzzle section before.

Petherbridge continued to praise puzzles that limited or eschewed two-letter words and/or unchecked letters. But one issue was dearer to her heart than any other:

When, oh when, will you puzzlers learn that all parts of a cross word pattern must INTERLOCK! Otherwise, you’re making a number of small cross words, each independent of the others. By some juggling, we fixed this one of Mr. [H.E.} Wright’s, but think of all the work you can save us by doing it yourself.

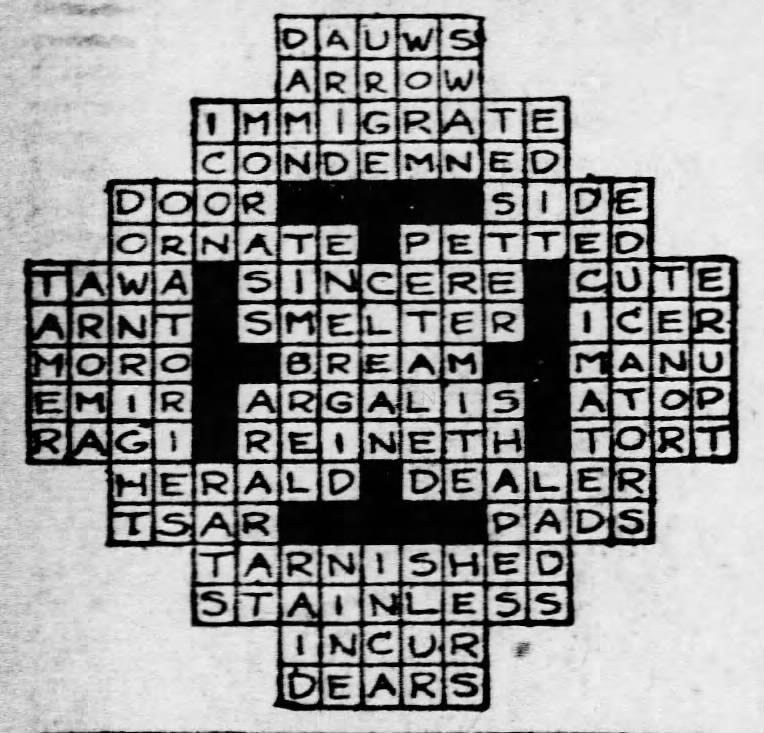

Puzzlers listened. More puzzles appeared in the World with all-over interlock, no unchecked (“unkeyed”) letters, or no two-letter words. Very few achieved all three, but there was a grid from “Professor,” about which Petherbridge wrote:

No unkeyed letters, a complete interlock with solid center, and no word of less than four letters. Having achieved this, the Professor closes with: “This, I think, will be my last contribution for some time.” Can you blame him?

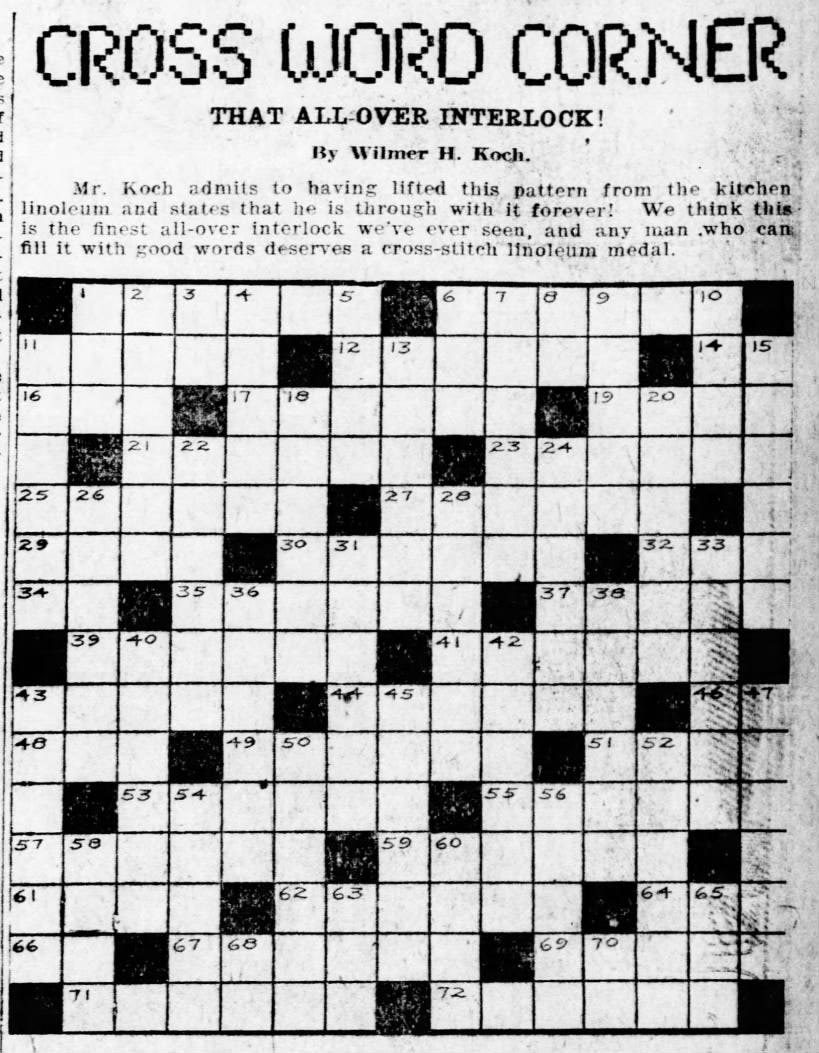

Other constructors Petherbridge celebrated this year were Wilmer H. Koch, for his wide-open, linoleum-inspired designs—

—and Kathleen Norris, a Ms. Manners-style commentator whose column was often the puzzle section’s neighbor.

Not all Petherbridge’s experiments were motivated by pure artistry. The third Cross Word Puzzle Book contains an early example of sponcon (sponsored content), a crossword that doubled as an advertisement for Venus pencils.

But even this shows a desire to experiment one’s way into discovering the art form’s future. Petherbridge’s promotional savvy worked in both directions. She had organized fundraisers for her alma mater: she knew the value of social gatherings. In the World and the pages of the book series, she took note of multiple crossword conventions across the country.

“Why Not Give a Cross Word Puzzle Party?” asked the back matter of the second and third Cross Word Puzzle Book volumes, noting that such had been a great success in the First National Cross Word Puzzle Convention, held at the Ambassador Hotel in New York on May 18, 1924.

Said convention was a watershed in early crossword history. That puzzle party was the first “world championship” competition. William Stearn II won, though a few months later, second-place finisher Madeleine Marshall issued a cheeky demand for a rematch. It was another woman who’d dethrone Stearn before the year was up—

But later for that. The convention’s main purpose was the foundation of the Cross Word Puzzle Association of America.

This organization had competition from the start in the form of Ruth Hale’s Amateur Cross Word Puzzle League, founded months earlier. Hale was a pioneer in the movement to let married women keep their maiden names. As founding president of the League, she directed its first meeting to codifying the following rules:

The pattern shall interlock all over.

Only approximately one-sixth of the squares shall be black.

Only approximately one-tenth of the letters shall be unkeyed.

The design shall be symmetrical.

Obsolete and dialectic words may be used in moderation, if plainly marked and in some standard dictionary, such as Merriam’s Webster, Funk & Wagnalls’s, Century, etc.

Foreign words that are more or less familiar and are easily accessible may be used and should be marked with the language to which they belong.

Technical terms that are found in a standard dictionary may be used.

Abbreviations, prefixes, and suffixes should be avoided as far as possible. When used, they should be plainly marked and must be legitimate.

[Regarding definitions,] the only requirement is common sense.

Synonyms that are too far removed from the word should be avoided, and also what Gelett Burgess calls smarty-cat definitions.

As Shechtman wrote:

If this sounds like all games and no fun, all rules and no play…it was. Hale was witty but never frivolous; she took herself and (for better or worse) her crossword puzzles very seriously. When a friend once accused her of lacking a sense of humor, she replied, “I thank God that the dead albatross of a sense of humor has never been hung around my neck.”

Odd, then, that the last of her rules cited Gelett Burgess, the “Purple Cow” author and humorist whose irreverent personality would soon clash with hers.

Early publicity for the Cross Word Convention suggested it might codify an even stricter set of rules:

At the conventions, Hale argued for more straightforward definitions in crosswords, Burgess against. The most complete contemporary account from the era comes from “Cross Ed,” the crossword editor of The Boston Globe. It’s rich with observed detail, putting you right into the mind and senses of someone who got to attend the event.

It’s…unfortunate that the mind in question held some obvious sexist condescension, especially toward Hale. But “Ed” did concede Hale’s basic argument was sound and drew enthusiastic handshakes even from those she criticized. Click here for a downloadable image of the article.

To some degree, Burgess and Hale’s debate over colorful, “personal” clues versus straightforward, fair-play clues continues today, with the “Gen Z” cluing style set against the style more traditional to modern newspapers.

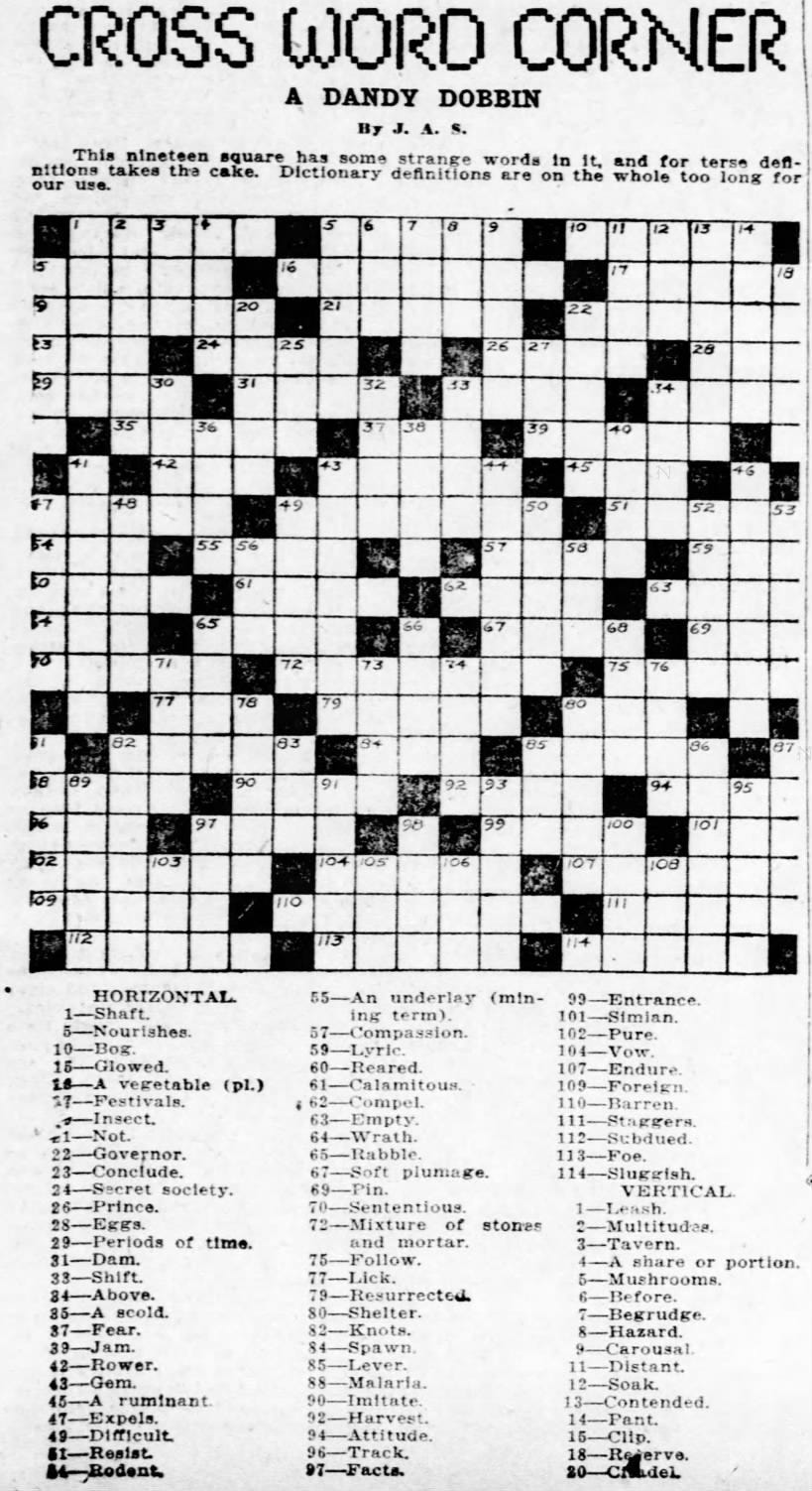

The World responded to this debate the way Petherbridge usually tried to improve the art form, by trying different things out and seeing how solvers liked them. It ran one “nineteen square” with extra-terse, super-straightforward clues…

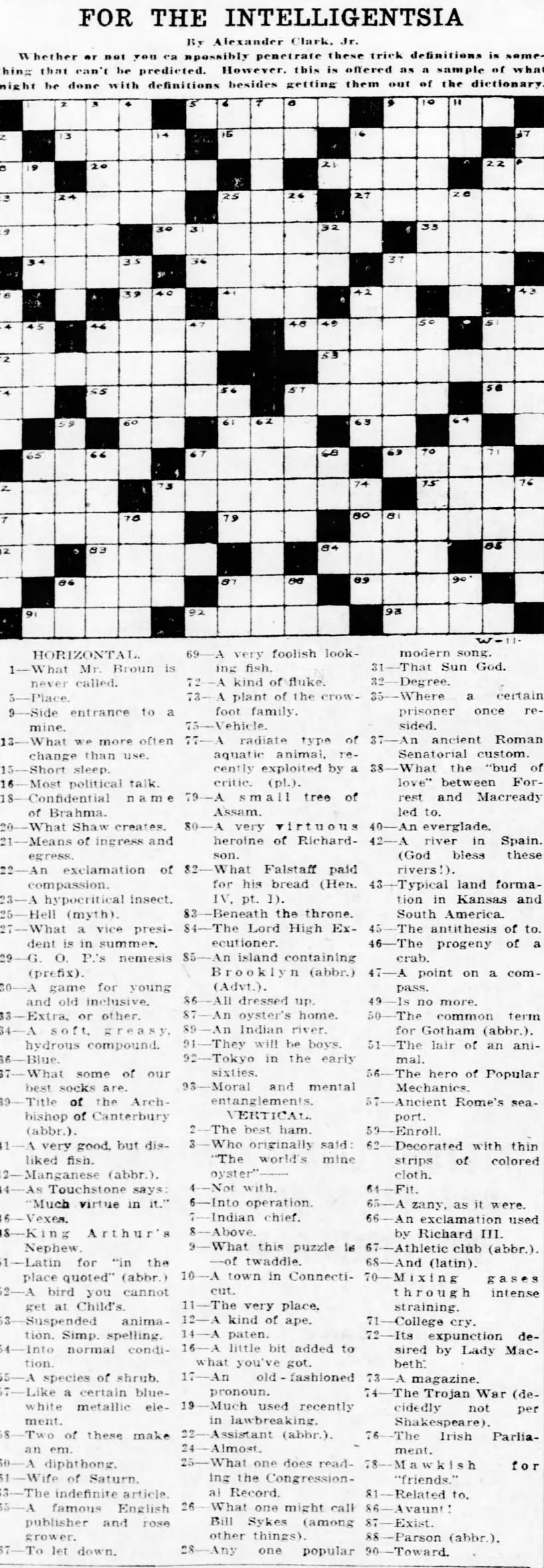

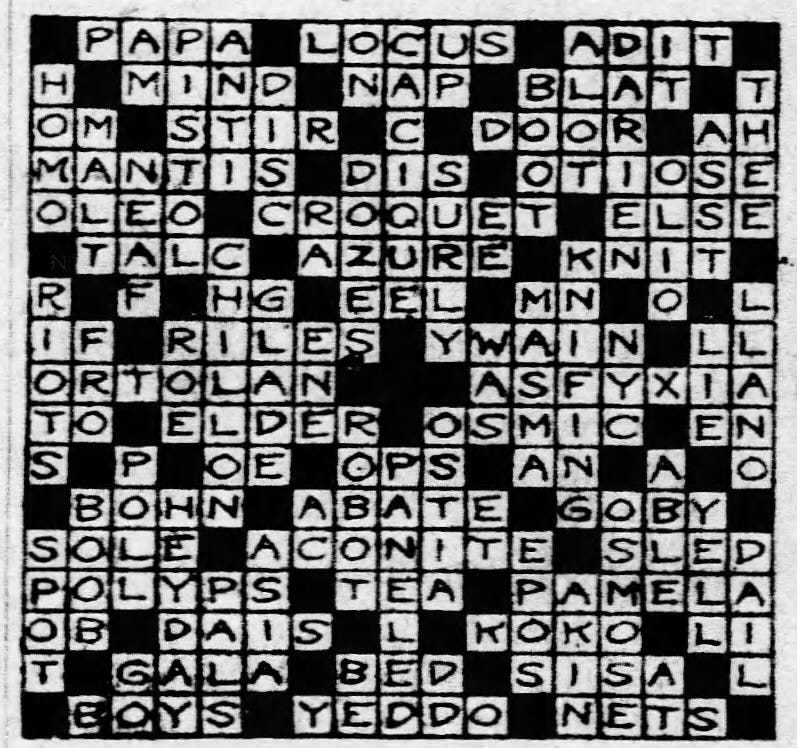

…and one “seventeen square” “for the intelligentsia” with a much more creative cluing style. 1-Across includes a reference to Hale’s husband Heywood Broun (another World employee). Clue: “What Mr. Broun is never called.” Answer: PAPA.

Hale and Broun had a six-year-old son, so this appears to be a reference to Broun’s popular newspaper column (which Hale sometimes ghost-wrote). The Globe might not have known quite what to make of Hale and Broun’s disdain for language like “Papa” and “Mrs. Heywood Broun,” but the World knew how to celebrate it.

Next: A craze’s ripple effects…