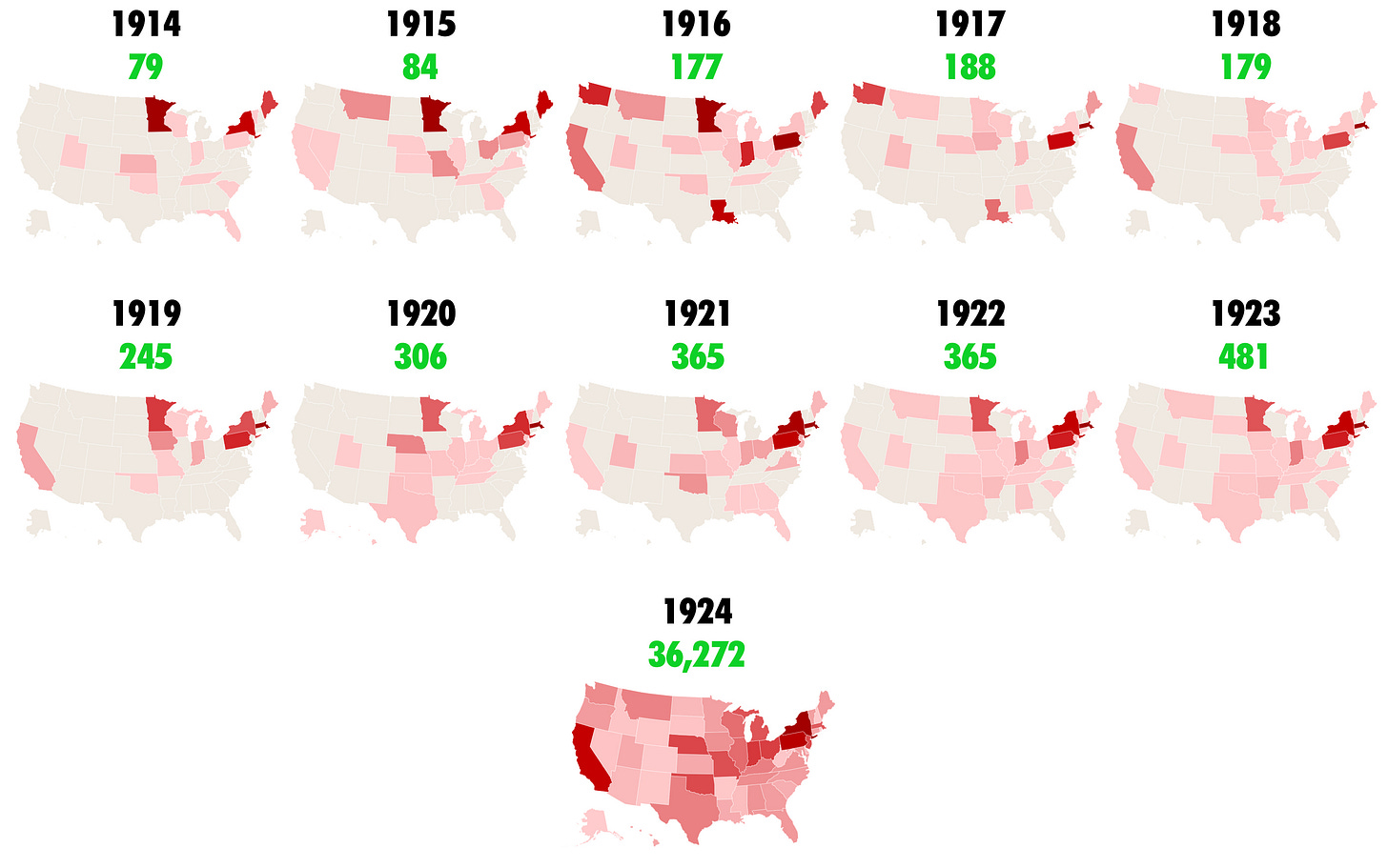

Newspapers.com has been invaluable in gathering information for this series, but 1924 is the year it starts returning too many results to sift through them all. Check out these year-by-year search numbers for the term “crossword” (with variants “cross-word,” “crosswords,” and “cross-words”):

These results show a couple of quirks—mentions in archived papers dipped in 1918 and had no growth from 1921 to 1922. And a few mentions (roughly 30-50 per year) used the other, now-outdated meanings of “crosswords.” But the picture is clear: in 1923 America, hobbyists were talking crosswords; in 1924 America, everyone was.

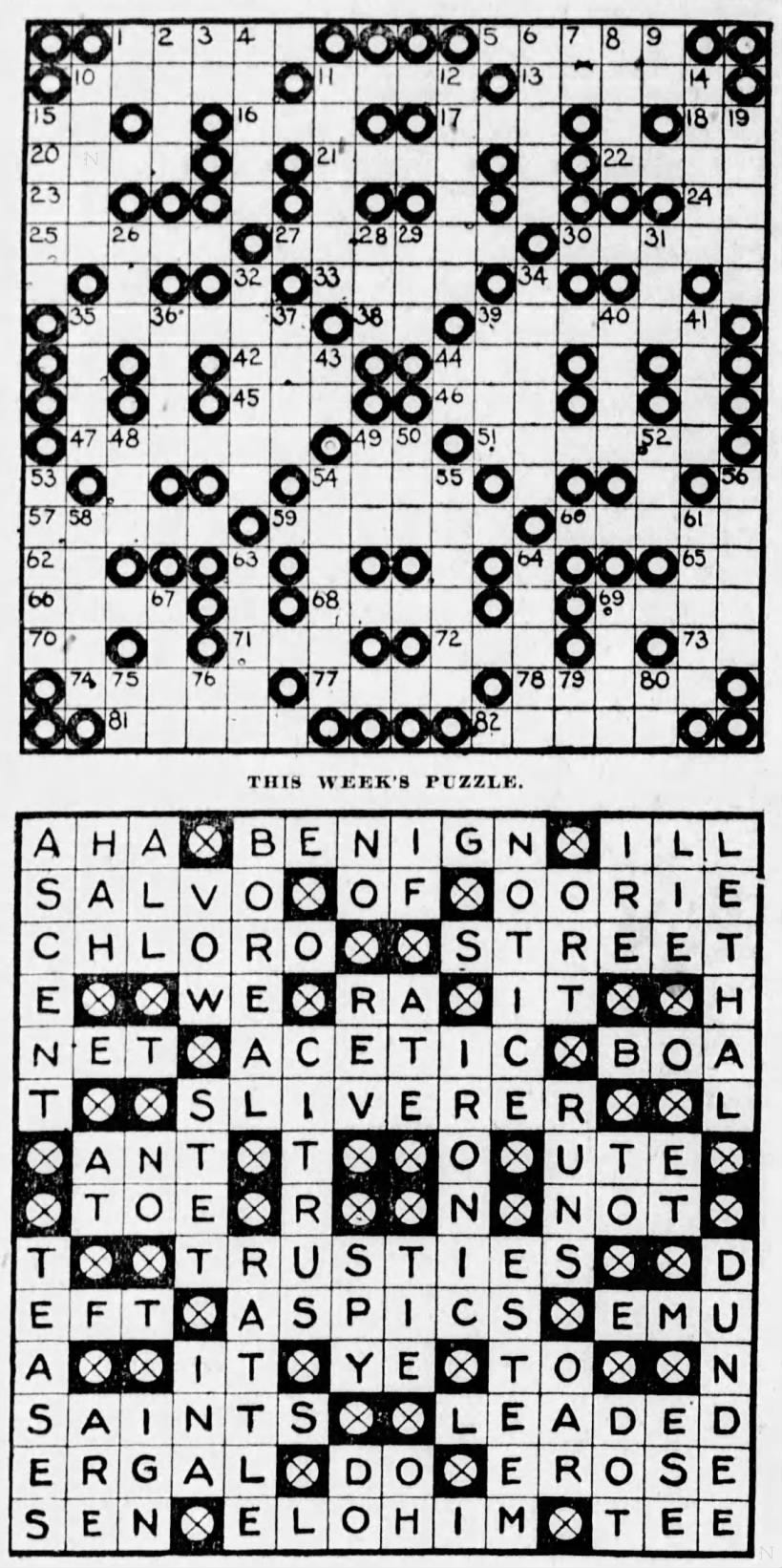

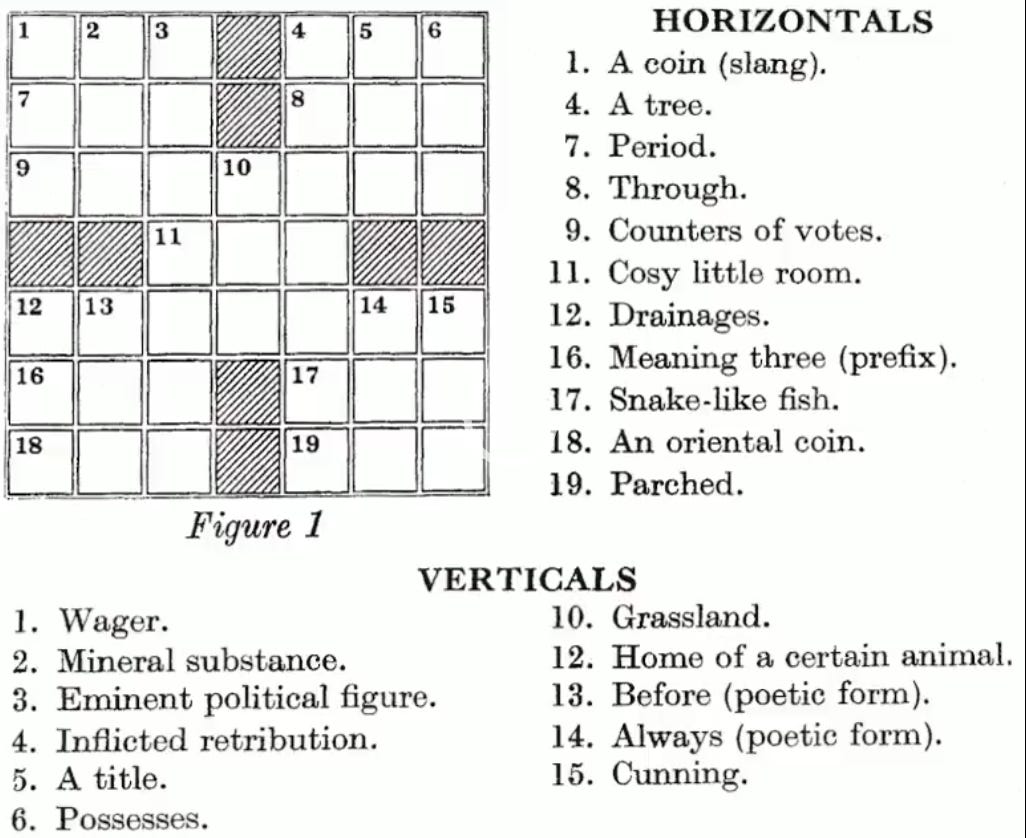

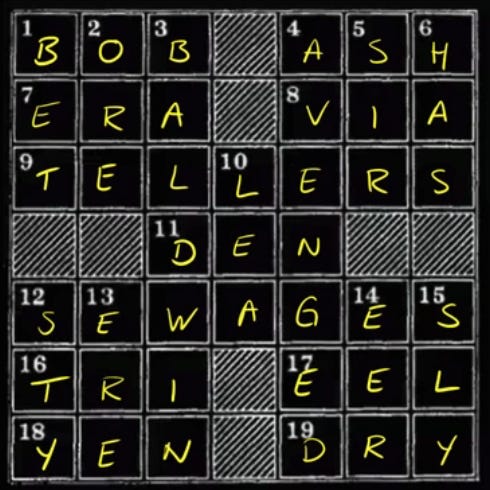

Crosswords remained mostly American and English-language at this point, with halting steps toward globalization. The Yiddish Jewish Daily Forward began publishing a Yiddish crossword, and the Sunday Express debuted a feature in Great Britain. Its first is notable for its vocabulary: many of its words are among the most popular words in crosswords to this day—ORE, EEL, ERE, E’ER, ETON, ERA.

This one has a curious history related in Ximenes on the Art of the Crossword:

This puzzle was one of a small batch offered by Mr. Wynne to Mr. C.W. Shepherd, a member of a syndicate known as “Newspaper Features,” who in turn sold half a dozen to the Sunday Express. As it happened, the first puzzle chosen for publication contained a word with an American spelling, and in order to eliminate it, Mr. Shepherd was forced to make a drastic reconstruction of the diagram: so this puzzle must be called the joint work of Mr. Wynne and Mr. Shepherd.

Note also BALDWIN at 3-Down, then the British prime minister. Was that the born-in-England, now-American Wynne’s contribution or the British Shepherd’s?

Meanwhile, in the States, crosswords were busy conquering mass media. And not just print media—you could hear them immortalized in song.

In 1921, F.P.A. had penned a tongue-in-cheek, lyrics-only “Crossword Puzzle Blues” for his column: now there were two actual blues releases, D.J. Michaud and Marguerite Bruce’s downbeat “I’ve Got the Crossword Puzzle Blues” (unavailable today) and the Duncan Sisters’ upbeat “Cross-Word Puzzle Blues.” “Cross-Words (Between Sweetie and Me)” was a love song from an anxious, insecure man—anticipating the next year’s release, “Crossword Mama, You Puzzle Me (But Papa’s Gonna Figure You Out”).

Those last two songs would share a theme: women love crosswords—and men just don’t get it and long for the days when women were interested in them instead. This theme would keep showing up in a lot of crossword-related media.

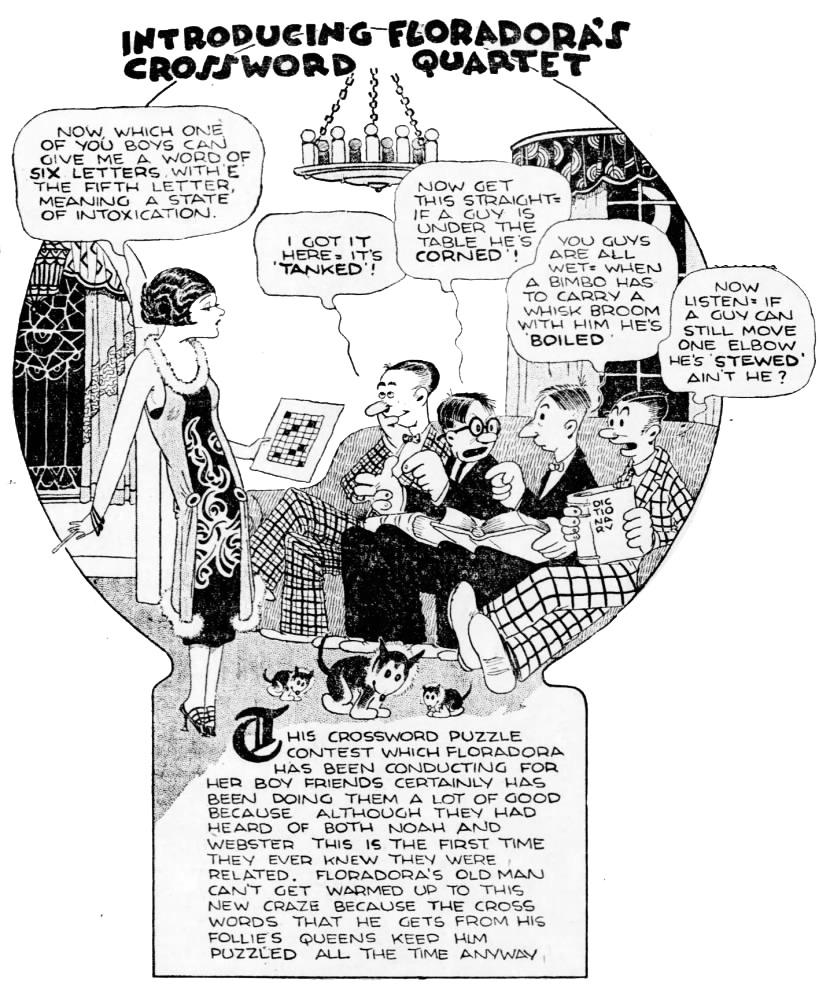

The crossword-solving “new woman” began to appear in magazine covers and cartoons of the time, too.

(The cigarette extending just past the panel border is a nice flourish by artist Sals Bostwick. Floradora and her boys were recurring characters, but the interest in the crosswords was new.)

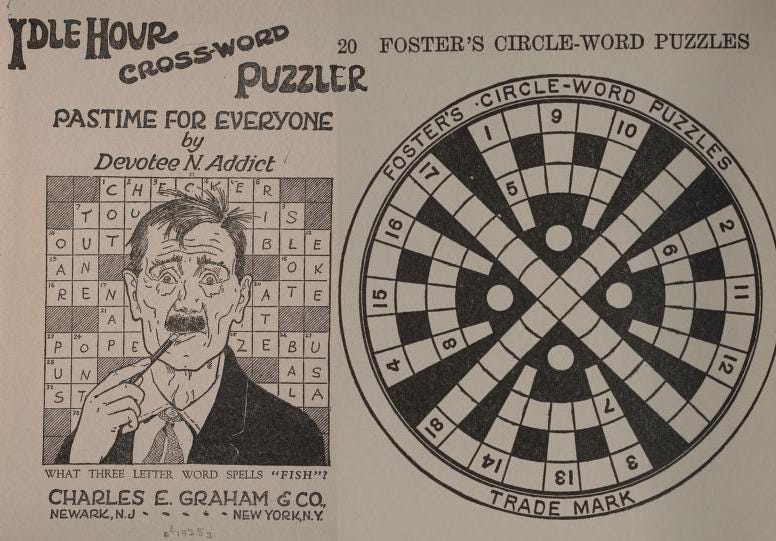

Men and women alike rushed to compete with The Cross Word Puzzle Book series. R.F. Foster, a prolific writer on games, developed his own trademarked “Circle-Word Puzzle” format (extensive review here). Carolyn Wells’ Crossword Puzzle Book featured 52 puzzles from the prolific author who’d already seen publication in the World. And the Idle Hour Cross-Word Puzzler pronounced the game a “pastime for everyone,” with a befuddled man on its cover (and a spoiler for the first puzzle behind him).

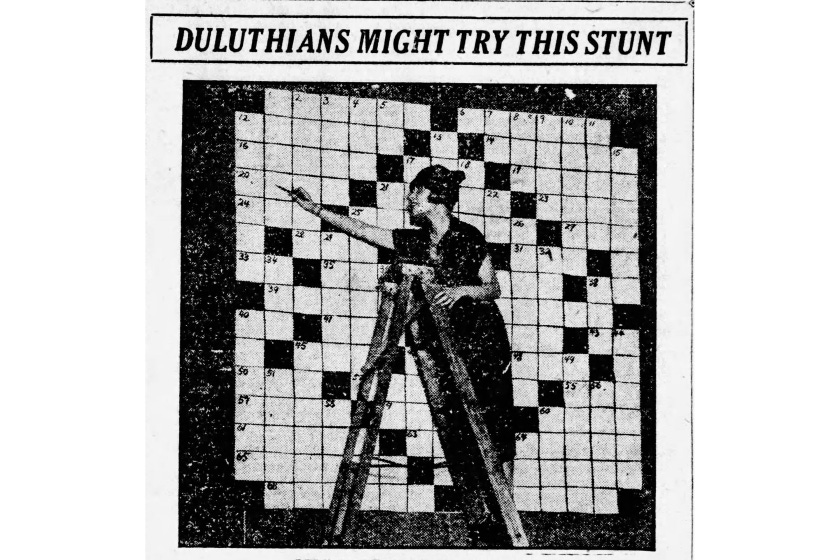

The New York Herald Tribune staged a two-day all-comers crossword contest some time after the Ambassador Hotel convention. William Stearn II won the men’s division, Ruth von Phul the women’s—and von Phul defeated Stearn in the final contest, securing the title of “international champion.” (Stearn and his wife did get the honor of being mixed-doubles champs.) Later that year, von Phul was solving puzzles in public for charity, turning the act into a kind of theater.

The multimedia spread of puzzles had even further to go in 1925. The most crossword-obsessed medium, though, was the medium where it all began: the newspaper.

Almost every paper was featuring crosswords, often daily, and some went further. The Boston Globe continued its post-game analysis, publishing readers’ responses to the puzzle—and to each other’s responses. Other papers like The Minneapolis Journal followed suit.

Perhaps noticing the distinctive cross-hatched squares on the Jerry King crossword, the Indianapolis Star released a series of crosswords with artistic squares in both unfilled grids and answers. Indianapolis solvers could tell at a glance that they were solving a Star puzzle.

Sensing they were lagging behind in this arms race, some papers threw money at the problem. The Chicago Tribune, the Des Moines Register, and the Daily Courier were among the papers offering cash for original puzzles. The Honolulu Star Bulletin, Reading Times, Star-Gazette, and Sunday Telegram offered cash prizes to solvers. Prizes were often in the five-dollar range, about $92.28 today. Those figures would go up.

Another sign of newspapers’ eagerness was that they would often put crossword-related material on the front page—stories about the Immigration and Citizenship Acts would just have to accept their lesser importance. One Alabama paper, the Alexander City Outlook, took this design priority as far as it could…

…although, in fairness, headlines like WASHINGTON’S ANNIVERSARY OBSERVED and CHAMBER OF COMMERCE ANNUAL MEETING HELD lead one to believe the Outlook wasn’t doing a lot of important or spine-tingling reporting in any event.

In short, in almost all spheres of life, the crossword was now ridiculously popular.

Maybe…too popular?

Next: The backlash.

![r/100yearsago - [November 15, 1924] Judge r/100yearsago - [November 15, 1924] Judge](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3c42cb74-ba55-4a89-b5fd-8cfa6efeb821_650x870.jpeg)