Whenever a new medium becomes successful enough to seem like it’s everywhere, some kind of backlash follows. It happened to novels, which Victorians called a gateway to narcissism, crime, and depravity. It happened to comic books—almost killing that industry in the 1950s. It happened to TV and movies, leading to restrictive content standards—at least for those media’s formative decades. It happened to role-playing games, video games, and several generations of music, with some early moralizers claiming all music was a path to the devil.

There is a case to be made against the addictive power of modern media. And some of the arguments for crosswords’ benefits—hawked without shame by newspapers and publishers—were specious and disingenuous. Doing crosswords won’t make you a genius; it does exercise certain mental muscles but leaves many others idle; a simple question-and-answer format is not a substitute for deeper thought.

You can have too much of a good thing—too much of anything, really—and some of the people in the grip of the crossword craze should have calmed down a little. Libraries had to keep buying new dictionaries as the old ones wore out from careless overuse.

But even the most extreme crossword fans didn’t seem half as crazed as crossword critics.

On December 27, The Tamworth Herald indulged in that favorite British pastime, belittling American culture: many other papers reprinted the piece. (Various sources, including near-contemporary ones, attributed this article to The Times of London. But I could find no evidence that the Times itself ever published the piece.)

CROSS-WORD PUZZLES: AN ENSLAVED AMERICA

All America has succumbed to the allurements of the cross-word puzzle. In a few short weeks it has grown from the pastime of a few ingenious idlers into a national institution and almost a national menace: a menace because it is making devastating inroads on the working hours of every rank of society.

Everywhere, at any hour of the day, people can be seen quite shamelessly poring over the checker-board diagrams, cudgelling their brains for a four-letter word meaning “molten rock” or a six-letter word meaning “idler,” or what not: in trains and trams, or omnibuses, in subways, in private offices and counting-rooms, in factories and homes, and even—although as yet rarely—with hymnals for camouflage, in church.

Crossword puzzles have dealt the final blow to the art of conversation, and have been known to break up homes. Twice within the past week or so there have been reports of police magistrates sternly rationing addicts to three puzzles a day, with an alternative of ten days in the workhouse, because wives have complained that their misguided spouses have been neglecting the support of their families.

Nearly every newspaper in the larger cities, and many in the smaller, now print a daily cross-word puzzle. It is estimated that no fewer than 10,000,000 people have caught the infection, and they spend half an hour daily, on the average, with the insidious pastime—that is to say 5,000,000 daily of the American people’s time, most of them nominally working hours, are being used up in trifling. It is, indeed, no longer a joke, this loss of productive activity of far more time than is lost by labour strikes…

Some of the puzzles will take an experienced hand as many as two hours or more to complete, being filled with rare and even obsolete words. Many of them involve prolonged search in dictionaries, books of synonyms, and atlases. And all of them make wanton waste of time. Many years ago, a misguided person thought to beautify some ugly stretches of shallow Southern rivers by planting them with wild hyacinths. The plan succeeded beyond all expectation. The hyacinths spread with amazing rapidity, choking the rivers at last and putting the authorities to enormous expense to clear out their channels again. The crossword puzzle threatens to be the wild hyacinth of American industry.

Silly Herald! You don’t enslave America with crosswords! As we now know, you enslave it with propaganda and partisan social media! (Let’s not even get into what the Herald seems to think of worker’s rights.)

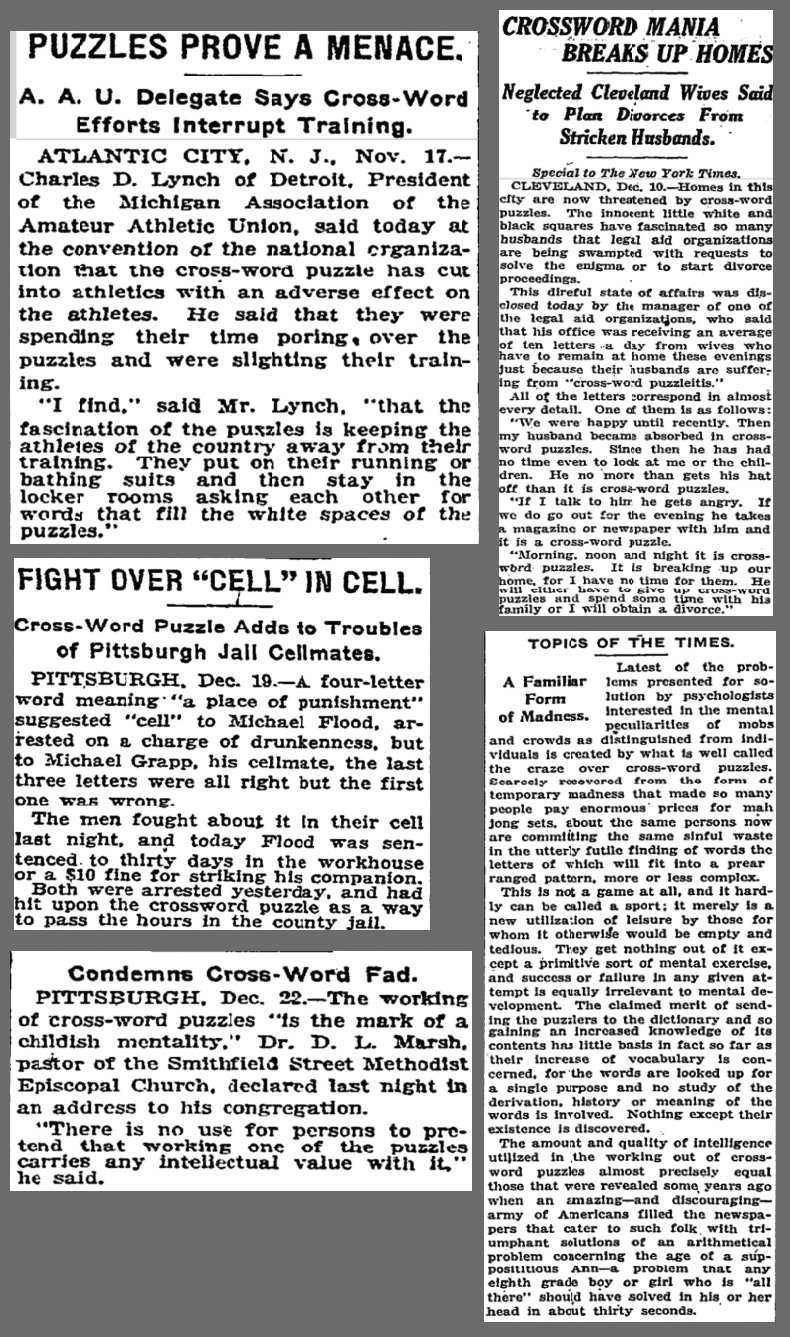

And the New York Times? Its 1922 sneer of dismissal was just a warm-up. For most of 1924, the NYT almost ignored crosswords, but in its last two months, it released no fewer than twelve articles focused on them.

Not all were negative. Two focused on theories that Phoenicians or medieval Europeans may have had primitive crosswords. Another few admitted possible benefits to the puzzle in certain circumstances, such as education—one piece concerned Princeton, another high school Latin, a third church sermons—or by revealing eyesight problems that otherwise might have gone unnoticed.

Even the headline “CROSSWORDS DELIGHT INSANE” wasn’t the condemnation you might expect: it reported crosswords’ soothing effect in mental institutions.

However, the positive NYT coverage always felt grudging and narrow. We suppose the cross-word might be all right, it seemed to say, if it’s helping the mentally or optically afflicted, or if it’s designed by some authority like a teacher or a pastor. After all, the ancients and medievals did it, though maybe they didn’t know any better, and civilization didn’t end.

And when the NYT went negative…it went all the way. One pictures a cigar-chomping J. Jonah Jameson writing the following pieces…

Failed athletes! Prison fights! Divorce epidemic! And it’s all so pointless! The “Topics of the Times” clipping above elicited the following response…

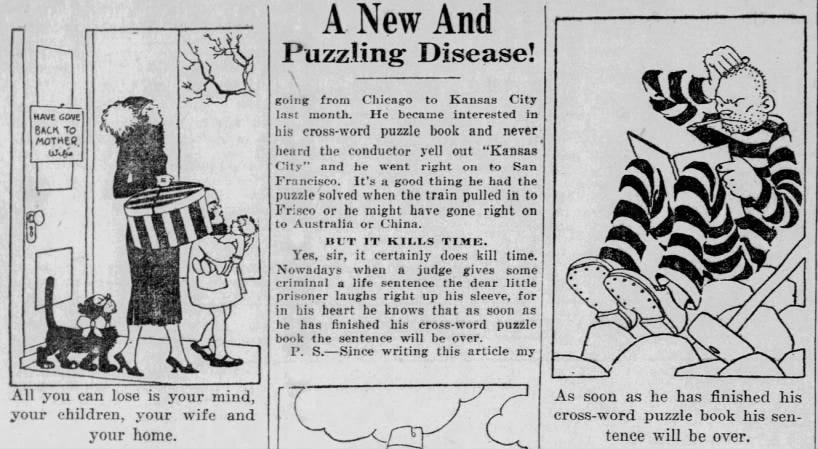

Some side-eyes weren’t the full-throated condemnations the NYT and Herald issued. Eddie Cantor’s “A New and Puzzling Disease” from The Baltimore Sun carries some of the same ideas as the NYT articles—that an obsession with puzzles can ruin your marriage and make you insensate to the world around you. But it carries them into the realm of humorous exaggeration, where they belong.

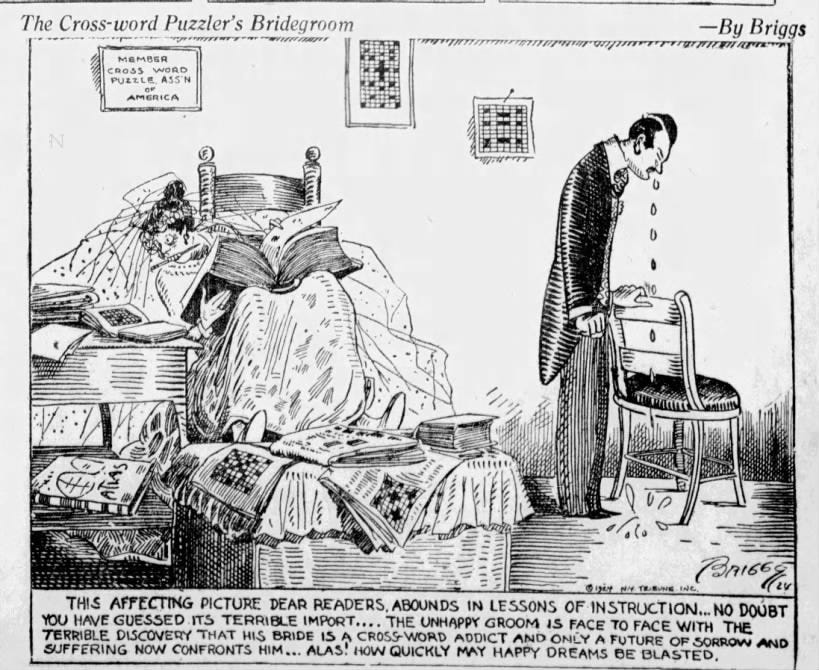

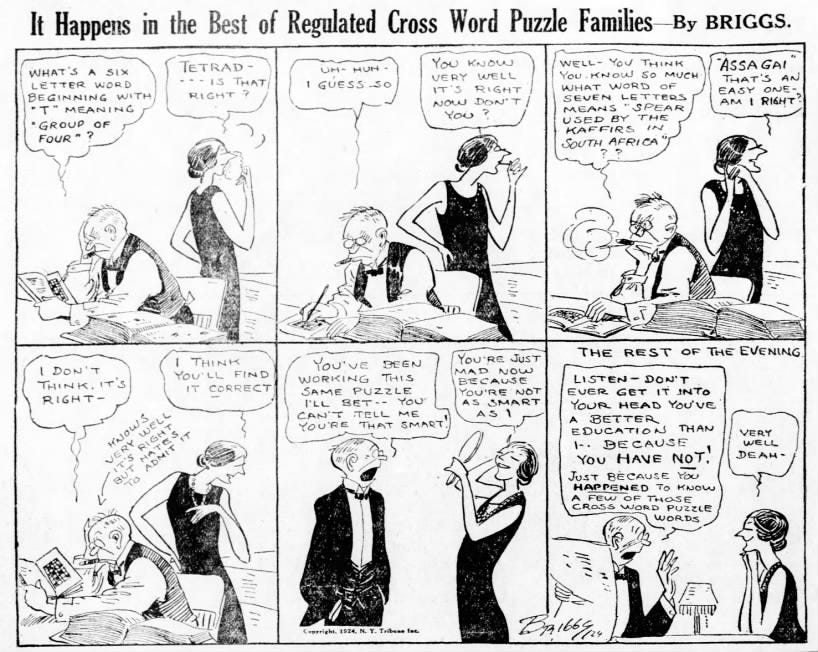

Clare Briggs could play with the marriage-ruining idea too…

But he seemed to get more mileage out of his bickering-but-stable couples, who would have found other ways to irritate each other if the crossword didn’t exist.

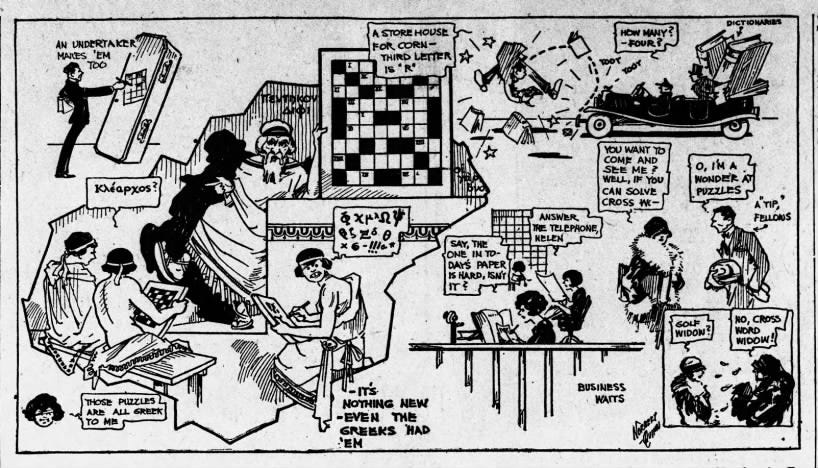

Even The Boston Globe, which couldn’t have been any further into the pro-crossword camp, published social criticism of the extremes to which people could take their fandom. To the question “Golf widow?” the woman at lower right replies, “No, cross word widow!”

One might expect Ernie Bushmiller to buy into the anti-crossword movement. He’d had a job illustrating anagrams for the World until the crossword’s expansion crowded out his feature. But in one of his last cartoons for the section, he took the side of the solver instead, using a little cartoon violence to illustrate a familiar complaint…

F.P.A. had declined to involve himself in the Cross Word Puzzle Book series, but had done his bit to promote it in his column (“Hooray, hooray, hooray, hooray! The Cross Word Puzzle Book is out today!”). About the panic, he wrote…

The booksellers have not mentioned the Menace of the Crossword. But that is obvious. The booksellers sell a lot of Crossword Puzzle books, and they don't care much whether they sell a Crossword Puzzle book, or a novel, or a book of poems. Those who fear Menaces fear them not as menaces to art, but to sales.

As for Margaret Petherbridge, she took the moral panic in good humor.

THE ROAD TO THE ASYLUM. By Rinix. Crosswords have been accused of many dire results, among others that they provide an easy way of landing in a padded cell. This one is worth taking a chance on, however…

She could afford to. At this point, the frowns of moralizers were only adding to the allure. When we return to this series for (thirsty) Thursday's installment, we'll see crosswords at their damn sexiest.

Tomorrow: Achievements in comedy music!

Wonderful blog today! Your selection of cartoons & comic strips are delighrful. I am

awed by your research and insights into the worlds of puzzle-making.

"But even the most extreme crossword fans didn’t seem half as crazed as crossword critics."

I also remember the crazed attacks against comic books in the 1950's. Crooked politicians did not and do not get that much attention.