Content warning for politics and seriousness. I won’t talk politics on here very often, but for various reasons, I felt compelled to do it today.

Accusation in a mirror means accusing someone else of doing the things you do, have done, or will do if given the chance. It’s a word game like many other word games I’ve discussed here: start with a true “I” statement, then change the pronouns and maybe the verb tenses. But this game can have dire consequences.

Commentators warned about the spread of fake news following Trump’s 2016 election. Within days of this, Trump began using the “fake news” label himself, and outlets peddling news that was actually fake followed suit. Trump’s talk of corruption and rigged elections likewise signaled his corruption and attempted election-rigging.

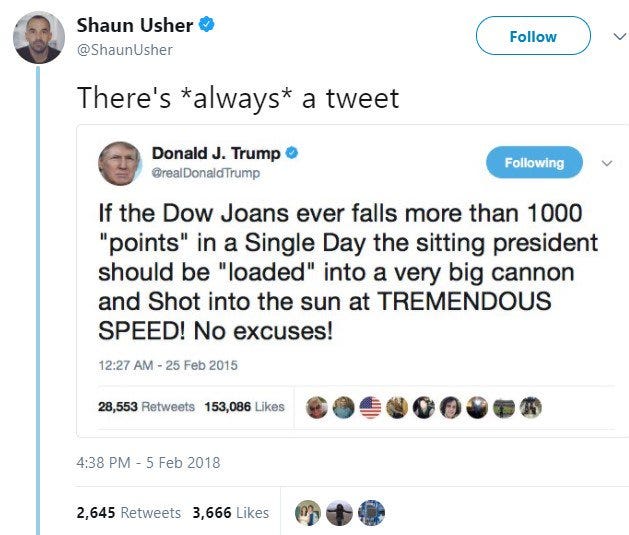

Back when Trump had a Twitter account, wordplayers could find gallows humor by making Trump-the-Obama-critic of 2012-2015 a commentator on Trump-the-President of 2017-2020:

“Accusation in a mirror” is a newish term for an old tactic. It has roots in generations of propaganda, but also in psychology—it can spring not only from advanced head games but also from unconscious projection. Trump’s advisors are sometimes shameless propagandists, but Trump himself seems to operate largely by instinct. You don’t have to be a narcissist to project your negative traits onto others, but it helps.

Still, in fiction, projection like this can be harmless and entertaining. Jane Austen characters sniff at those poor blind souls less enlightened than they, only to be humbled when it turns out they’re the blind ones after all.

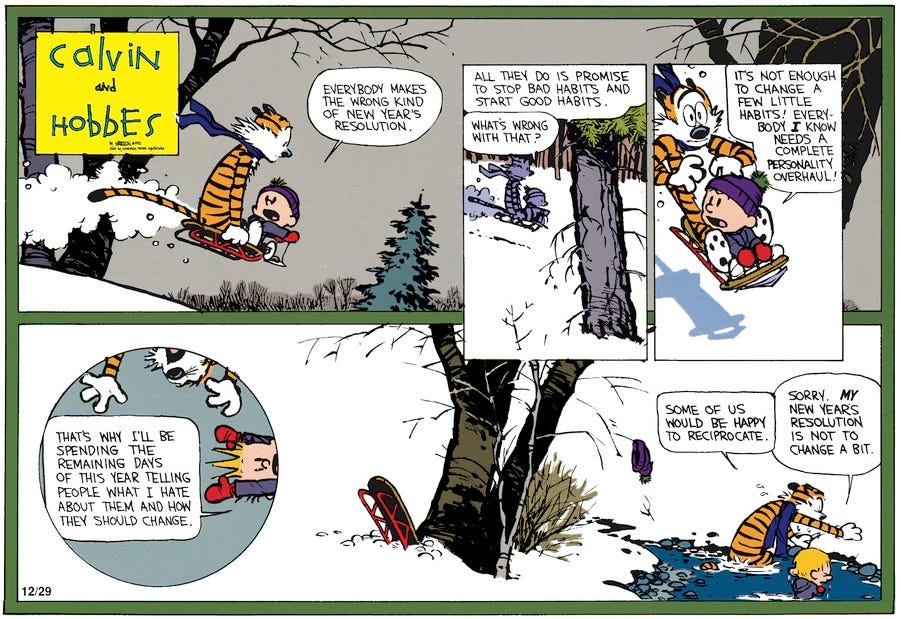

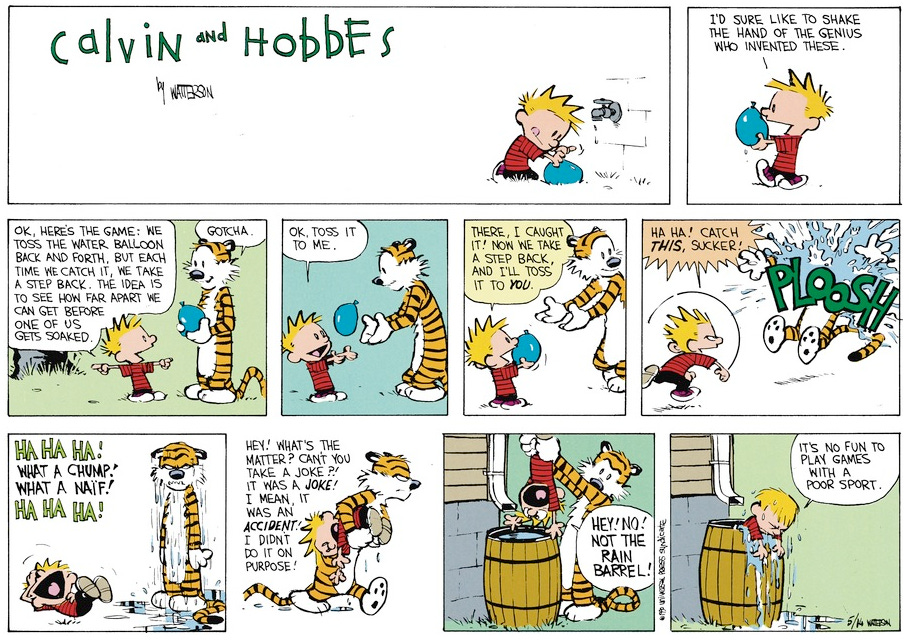

In the examples below, Calvin and Hobbes’ Calvin calls others “in need of a complete personality overhaul” and “a poor sport,” labels that’d apply more to him, and Seinfeld’s George misidentifies which member of his social circle is at the bottom of their totem pole.

What makes these examples funny, even sympathetic, when others are disturbing or terrifying? We recognize a bit of ourselves in Calvin and George—everyone’s got a little bit of ego, at least—but we also recognize they’re not hurting anyone else much. Their blindness might annoy their friends and family, but that’s all, and it’s also likely to limit their opportunities in life if they never grow out of it. (Calvin has a pretty good chance of doing that. George, not so much.)

The problems come when such accusation in a mirror does harm others and is rewarded with power. In our current political reality, that’s a valid tactic. Trump acts on instinct, but his advisors do not, and since Steve Bannon and Steve Miller, shameless propagandists have always had a place on Trump’s staff. The term “accusation in a mirror” was invented by a 1990s propagandist, an anonymous figure who wrote to his fellows about how to justify the Rwandan genocide.

As a strategy, accusation in a mirror’s goal is not to persuade the entire public, but to persuade enough of it that the rest ends up confused and divided. Given a loud enough megaphone, it can succeed. Given a divided media landscape, it can succeed.

It also opens the door for “tu quoque” fallacies down the line. Tu quoque translates to “you too,” and they come in a few flavors:

“I’m innocent! It’s my opponent who steals cookies! I told you he did [in the lying, accusation-in-a-mirror speeches I started repeating over a year ago]!”

“What does it even matter if I stole some cookies when my accuser also steals cookies? I’ve already told you he did [in the lying…et cetera]”

“Grow up! This is the real world: everyone steals cookies!”

It’s important to maintain a sense of humor in troubled times, but I’m afraid these arguments have ruined a whole species of joke for me, the one in which the punchline is “Ha! All politicians are corrupt!” Can one get along in Washington without a little moral compromise here and there? I’m not sure one can…but there are different levels of corruption, and that distinction needs to be important. I heard a lot of people saying “I can’t sanction either side” as they abstained from the 2016 US election. Most of them had reason to repent that decision after the fact.

Like most rhetorical devices, accusation in a mirror does lose power when people catch on. And that opens the door to exploit its weakness. Since it signals what the speaker will do, it allows us to form counterstrategies in advance…once we’ve caught on to it enough to speak its language.

So…let’s catch people on, eh?

Next: Z!

An important post. Thank you for writing it. Much wisdom in Calvin & Hobbes.

One essential question as Democracy is under siege: "Whom can we trust to tell us what matters"

Great post. I'm curious what prompted this?