Confession time!

Although I’ve been a vocal critic of their failures (seriously, how hard is it for a computer to produce palindromes reliably?), I have played with AI and LLM services—and probably will keep doing that. That’s a controversial decision for a writer in 2024; some of my fellow creatives see any such usage as collaborating with the enemy.

I find it a steady source of inspiration. And even if I didn’t, knowing how prompt engineering works strikes me as a basic requirement for understanding things I want to understand about language in the 2020s. (Plus, it might help me make a little money.)

I don’t support the contention that LLM use constitutes plagiarism or copyright infringement, for reasons outlined by Cory Doctorow on his site. His subject was AI art, but the argument is transferrable to writing:

While specific models vary widely, the amount of data from each training item retained by the model is very small. For example, Midjourney retains about one byte of information from each image in its training data. If we're talking about a typical low-resolution web image of say, 300kb, that would be one three-hundred-thousandth (0.0000033%) of the original image.

Typically in copyright discussions, when one work contains 0.0000033% of another work, we don't even raise the question of fair use. Rather, we dismiss the use as de minimis (short for de minimis non curat lex or "The law does not concern itself with trifles"):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_minimis

Busting someone who takes 0.0000033% of your work for copyright infringement is like swearing out a trespassing complaint against someone because the edge of their shoe touched one blade of grass on your lawn.

Cory has other issues with AI-based work. So do I, but my issue differs from his, and it’s one that I don’t see AI think pieces raise very often.

It’s a simple issue: training an LLM requires a vast quantity of writing…and quantity tends to compromise quality.

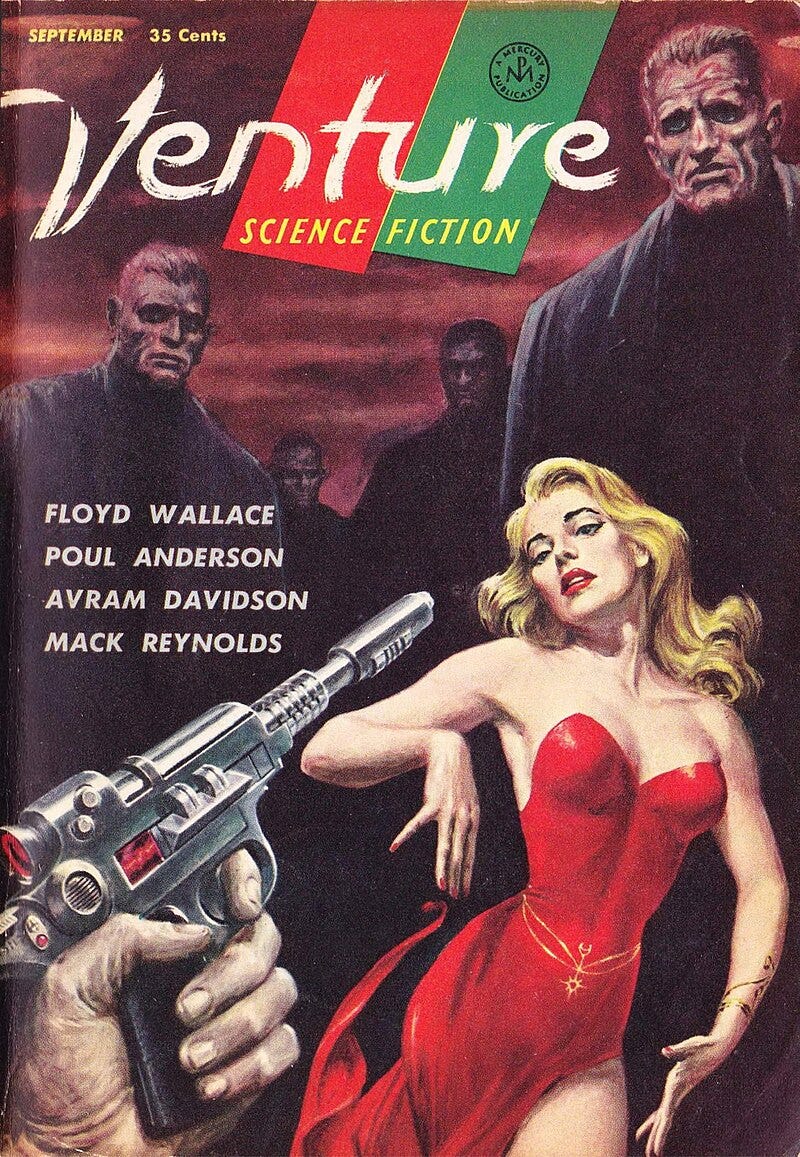

In Venture Science Fiction, science-fiction author Theodore Sturgeon coined the adage that “90% of everything is crap.” Sturgeon’s Law was first applied as a defense of science fiction—i.e., yes, the critics are right that a lot of sci-fi writing is terrible, but no more so than a lot of so-called “literary” writing or writing in other genres.

(The pulpy cover of the magazine he published this revelation in, seen above, didn’t exactly make it look like a statistical outlier.)

LLMs, however, believe in a “wisdom of crowds” model. To work at all, they need to sift through huge amounts of data. How likely does it seem that most of that data—enough of it to produce a statistical mean—would be Sturgeon’s crap?

Especially since a lot of online writing has already been tailored more to what performs well in SEO or drives engagement models than to what sparks true understanding or joy in the human heart.

LLM enthusiasts are trying to find some ways around this, such as paying well-respected news outlets for the use of their articles as training data. I support this. The New York Times and The Washington Post ain’t perfect, but they’re sure better sources to be working with than the essays of some climate-denier on Facebook. But these more limited models are likely to be less flexible overall, unable to adapt beyond the kind of work that the NYT and WaPo normally cover.

The canon of great literature is too small to be a useful LLM training ground, and even if it weren’t, it’d still be too varied. What kind of “average” writing would you get if you took your data from just, say, Nabokov and Beowulf?

Scale that up and you’ve still got problems. True greatness in writing often comes from bold outliers, from the unlikely word choices, not the statistically likely ones.

You can adjust for this problem somewhat—Sudowrite allows you to specify that “You must avoid cliches.” And as I said, I’m still making use of the systems, exploring ways to adjust them further. Using them helps me think in new ways, and my eccentricities can use a little grounding. Typical word choices sometimes balance me out a bit.

But there are things LLMs can do and things they can’t, and a cliche-compensator is no substitute for true imagination. So here’s Campbell’s Law of LLMs (as distinct from the more general Campbell’s Law):

Systems designed to pursue probability cannot, on their own initiative, pursue excellence.

That part is still up to us.