Biblical Acrostics (3 of 3)

In praise of the unpraiseful.

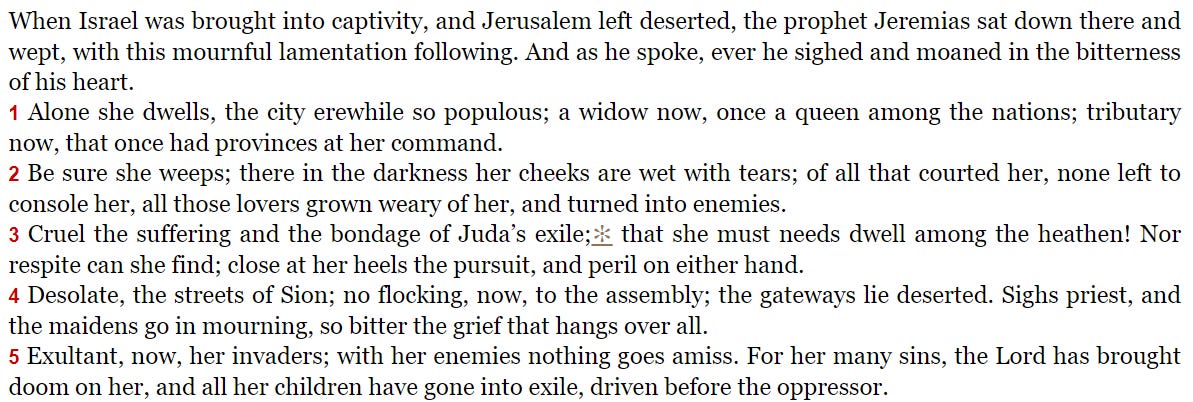

The Biblical books that contain acrostics all have pretty self-descriptive titles. Psalms is mostly songs of joy, Proverbs words of wisdom. The Book of Lamentations, like much of The Babylonian Theodicy, is a darker, more depressing work. As with our other examples, the Knox Bible renders its acrostics in acrostic form:

Lamentations is a set of five poems, each independent of each other but all concerning the 586 BCE sacking and destruction of Jerusalem. This puts the poems in the Mesopotamian tradition of “city laments,” a tradition I think has a lot of relevance today. (I’ll leave the question of which cities deserve modern-day lamentations to your imagination.)

There is no “O God, why have you forsaken us” to these poems of mourning, though. The author (the prophet Jeremiah, by tradition) makes the case that Jerusalem earned its woes and that God’s punishment of the city was just, even merciful.

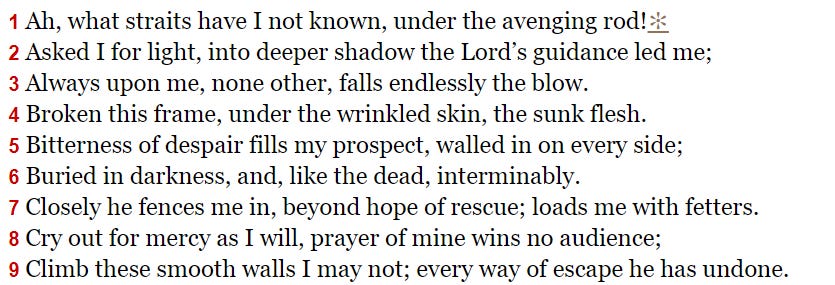

Lamentations 1-4 are all alphabetic acrostics, with Lamentations 3 going three times as long as the others and devoting three verses to each letter:

That just leaves Lamentations 5, twenty-two lines long—which suggests an acrostic—but in a totally non-acrostic structure, as if the chaos of Israel’s current existence has now wrecked even the poetic form used to express it. (I’ll stick to Knox in the quotes below, just for comparison’s sake.)

This is probably the highlight in the history of acrostic literature. There are other landmark cases, though they tend to spell out words and phrases rather than span the alphabet. A short passage in the Aeneid spells out the name MARS (Roman god of war). Medieval acrostics, following the example of the classics, usually spelled out the name of the poet’s patron or made a prayer to a saint.

In modern times, acrostics are often used to conceal a message of protest or spite from the intended recipient, leaving it hidden for more agile minds to discover. One such message was in a notorious veto Arnold Schwarzenegger wrote as governor in 2009 (I’ve highlighted the relevant letters for clarity):

When called out about this, Schwarzenegger claimed it was coincidence, but the odds against composing such a message accidentally are so high as to be effectively impossible. Statistician Philip B. Stark tried several statistical models to determine how unlikely it was—his most convincing, in my view, puts the odds at 1 in 486,804,391,348.

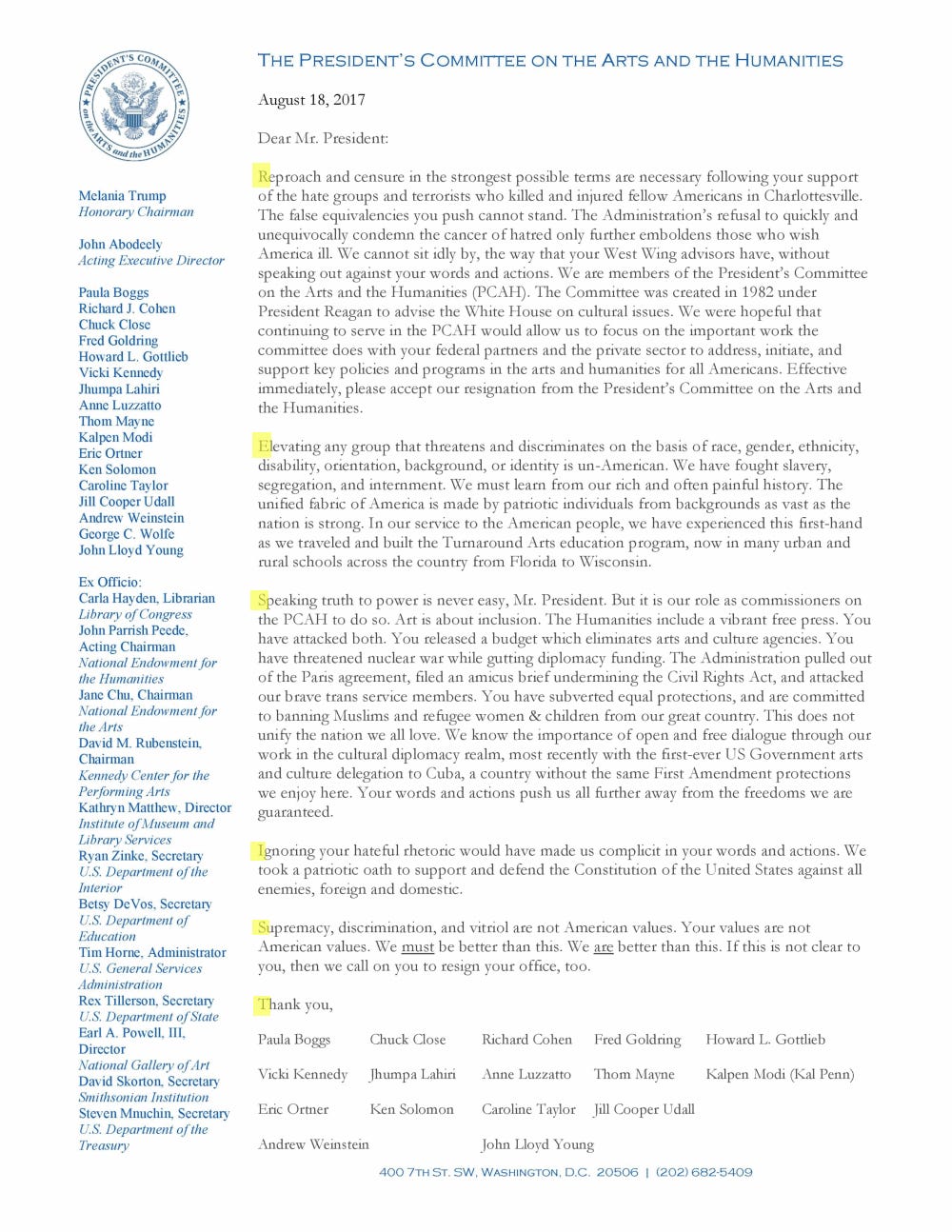

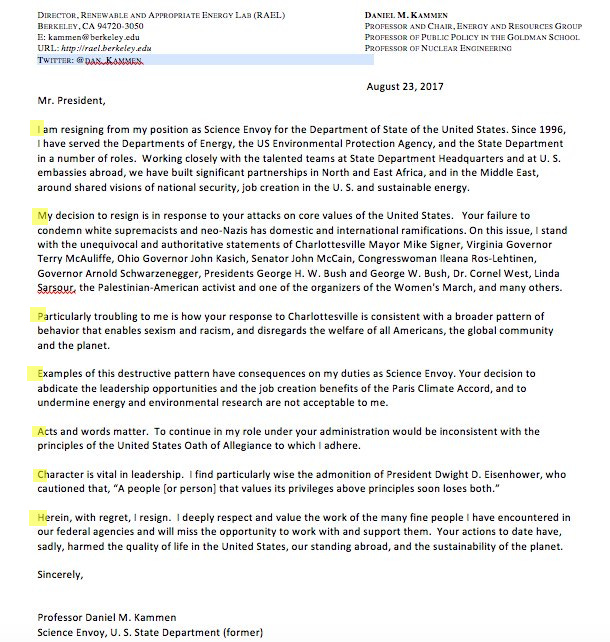

Similar messages appeared in two resignation letters aimed at the Trump administration, within the same week of August 2017, in response to Trump’s response to the violent Charlottesville rally. These acrostics were paragraph-based, not line-based, and therefore a bit more subtle, though the press picked up on them in no time at all. Again, highlights are mine:

Acrostics are a simple art and don’t get a lot of present-day exposure, but that’s just what can make them an effective tool—when they’re least expected.

Tomorrow: It’s deadline time for the Journal!