Unsurprisingly, Will Shortz’s second Word Ways piece about British word puzzling was as interesting as his first. As I did with the first piece, I’m giving a brief summary below, but you really should take the time to look through the original.

“By the late 1700s and early 1800s, many new types of word puzzles had become popular in England. Charades began to rival enigmas and riddles in prevalence, and anagrams, transpositions, reversals, beheadments, and logogriphs all began to appear with greater and greater frequency.”

Word fans, or cryptic crossword solvers, probably know most of those—although the distinction between anagrams and transpositions, if any, depends on who you talk to.

The logogriph is rarely seen today, though. It was a combined type, showing various tricks that could be performed with shorter words: beheadments, curtailments, transpositions, and so on. I’m a little pressed for time as I compose this and Wikipedia has a very compelling explanation for one, so I’m going to quote it directly. It gives the following example of a logogriph, created by Lord Macaulay:

Cut off my head, how singular I act!

Cut off my tail, and plural I appear.

Cut off my head and tail--most curious fact,

Although my middle's left, there's nothing there!

What is my head cut off?--a sounding sea!

What is my tail cut off?--a flowing river!

Amid their mingling depths I fearless play

Parent of softest sounds, though mute for ever!

In explanation, cut off COD’s head and it becomes OD (i.e. odd, or singular); cut off its tail, and it becomes CO (company, plurality); cut off both to leave O (nothing, emptiness); the head of the word is the letter C, which sounds like SEA; the tail is D, which sounds like the River Dee, and COD itself may play in the depths of both.

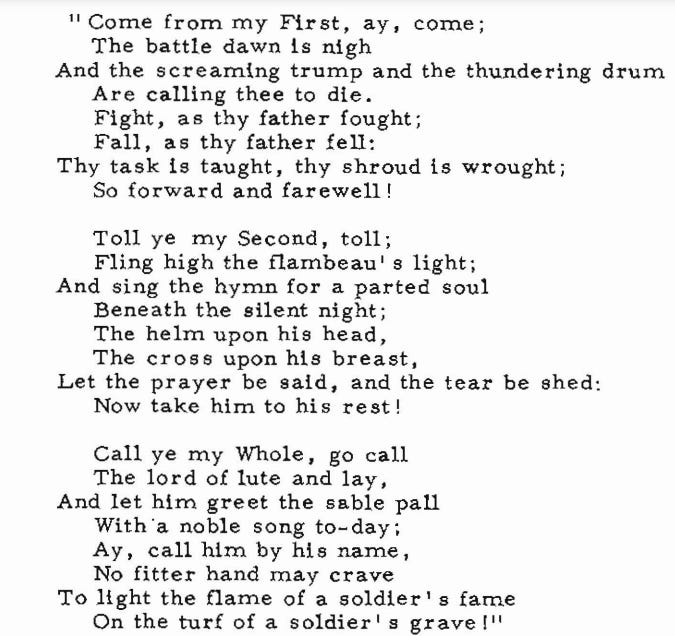

Ego also compels me to include this example of a charade by Winthrop Mackworth Praed from the Shortz piece…

The “First” here is CAMP, the “Second” is BELL, and the whole is CAMPBELL—alluding to the then-popular poet Thomas Campbell.

Shortz sums up by surveying the public attitudes toward puzzles at this point. He found that they inspired a mix of contempt and respect—and that both responses were earned, as many puzzles were of very poor quality but some were brilliant enough to hold up well even today. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.