Crossword Prehistory: Egypt

More on the oldest of all the cross-word structures.

Today’s update owes most of its content to Sergio Barcellos Ximenes’ “Cultural History of the Crossword Puzzle.”

High Priest Neb-Wenenef was a high achiever in life, leading worship of three different gods, holding three different superintendent positions and at least three other leadership roles, the most colorful of which was “chief of secrets.”

One of those secrets? Acrostic arrangement.

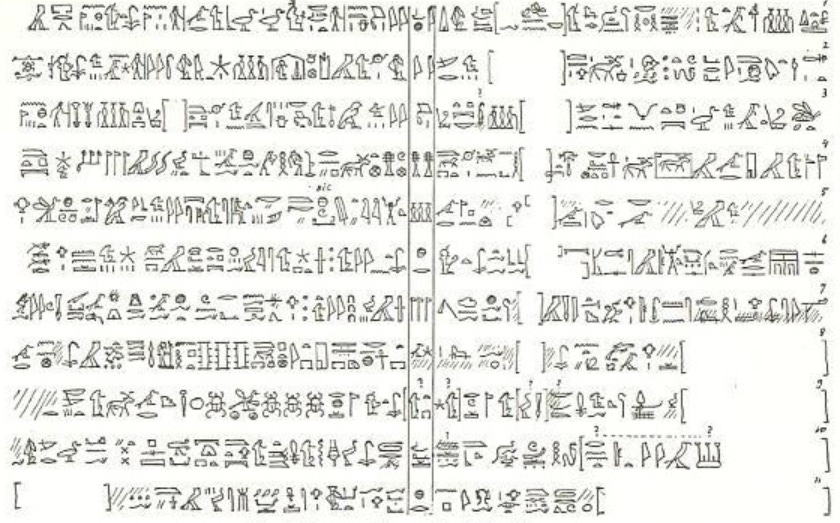

When Neb-Wenenef died around 1290 BC, in the service of Ramses II, his tomb contained a stela holding a series of hieroglyphs in praise of Osiris, protector of the dead. Nothing odd about that: most Egyptians wanted to get in good with the new boss when they died. But crossing the middle of its 11 lines was a central, vertical acrostic, a hymn: “The Venerated One, worthy of the graces of the gods of the kingdom of the dead, with Osiris.”

A later stela, probably from 1085-820 BC, uses several acrostics well apart from each other. Other hieroglyphic arrangements from the mid-1100s BC were even more crossword-like. One such came from the reign of Ramses VI (1141-1133 BC), as part of an extravagant memorial to Ramses’ favorite wife, Nefertari. Its inscribed dedication below the body text includes the line, “written to be read in two ways.”

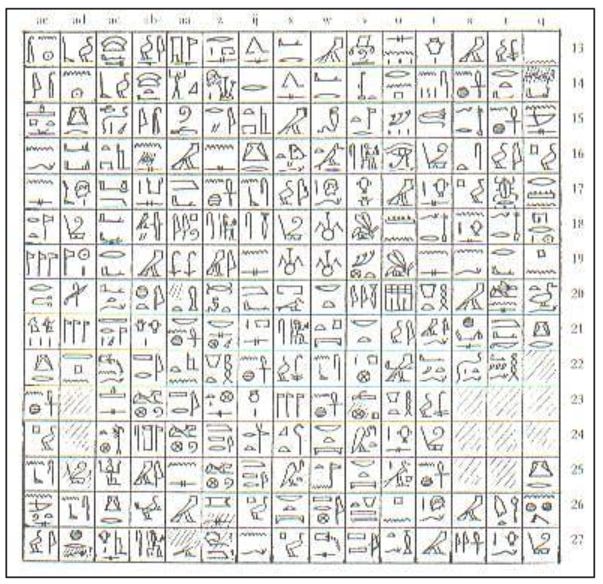

The real find from the Ramses VI era, though was the Paser stela, a limestone slab now on display in the British Museum. This remarkable work was meant to be read three ways: across, down, and (probably) around its perimeter. It’s a hymn to Mut, a mother goddess treated as queen of the gods in Karnak, where the stela was found. (Isis who?) Unlike the tomb stelas, this one was made for public consumption. Maybe that’s why it included double entendres and other wordplay—not uncommon in Egyptian writings of that era.

Paser was another go-getter: a vizier, a high priest of Amun (Mut’s husband), and a noted architect. But his achievements didn’t always seem effortless. Scholars like Jan Zandee have noted that the hieroglyphs on the Paser stela have some unusual arrangements. Though they probably “worked” for ancient Egyptians, they may have felt like awkward crosswordese.

Still, considering the scale and complexity of the stela, these wobbles are easy to forgive. Though it’s been badly damaged over the years, it was once an 80x80 grid, with that extra “perimeter” dimension. That’s 6400 squares…and unlike modern crosswrord designers, the stela wasn’t using any black squares for interruptions. I shudder to contemplate it.

But was this the first crossword grid (well, cross-hieroglyphic grid) in ancient Egypt? Turns out that’s a no.

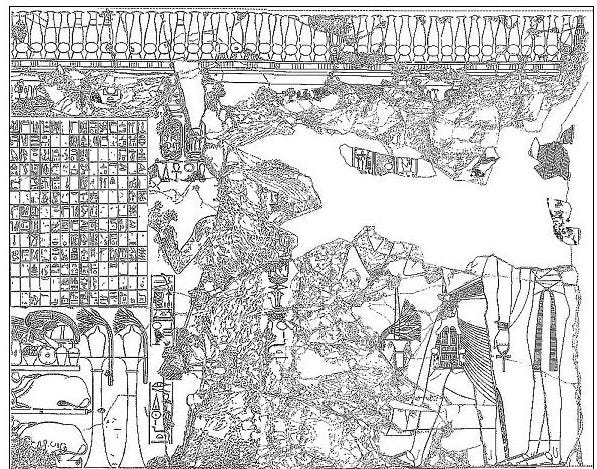

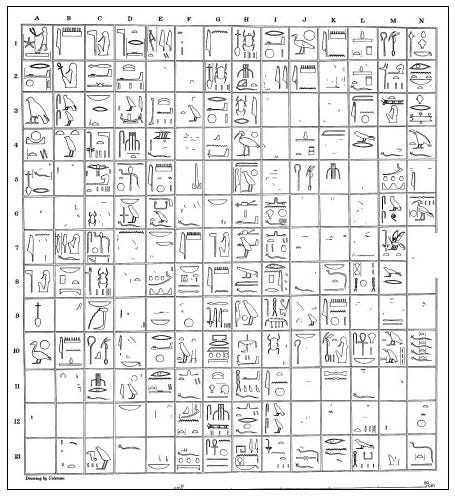

Another stela with a grid comes from the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten, back when he was going by Amenhotep IV (so about 1352-1348 BC). Kheruef, a royal scribe, served as steward for Amenhotep IV’s mother and wives. On the left of Kheruef’s tomb as you enter it, Amenhotep IV is dedicating a large offering to Ra-Horakhty—ironic, since as Akhenaten, he’d try to turn Egypt away from the old gods.

Above the stacked offerings is a rectangular 14x13 grid, 1.48 meters high and 1.36 wide. Its hieroglyphic texts of worship are written across and down.

Shortly before Akhenaten’s reign would introduce a new path of religious thought, it was playing with this novel way of arranging symbols. The grid predates all the other examples given here—we just found it later. Of course, we still don’t know for sure if this was the first major work to use a cross-wise arrangement. It’s just the oldest to have weathered the cross-breezes of millennia and make its way down to us. Egyptology offers puzzles of its own.

Delightful knowledge. Thank you. As soon as language was invented, playing with words or pictographs must have enlivened daily communications. After the discovery of sex, juggling with rocks, and drawing on cave walls, soundplay may have been our first entertainment. Impressionistic grunting? Then word play, introduced by one of T. Campbell's ancestors.

Must be some wordplay in The Bible?