Last time out, we were discussing Frederick Planche’s 1872 Guess Me and the small word-square puzzle hidden inside its pages. I don't have the resources to claim whether that was genuinely the first of its kind, but a lot of interesting crossed-word constructions were happening in that period. A couple of years later, in November 1874, the American magazine St. Nicholas published a word diamond.

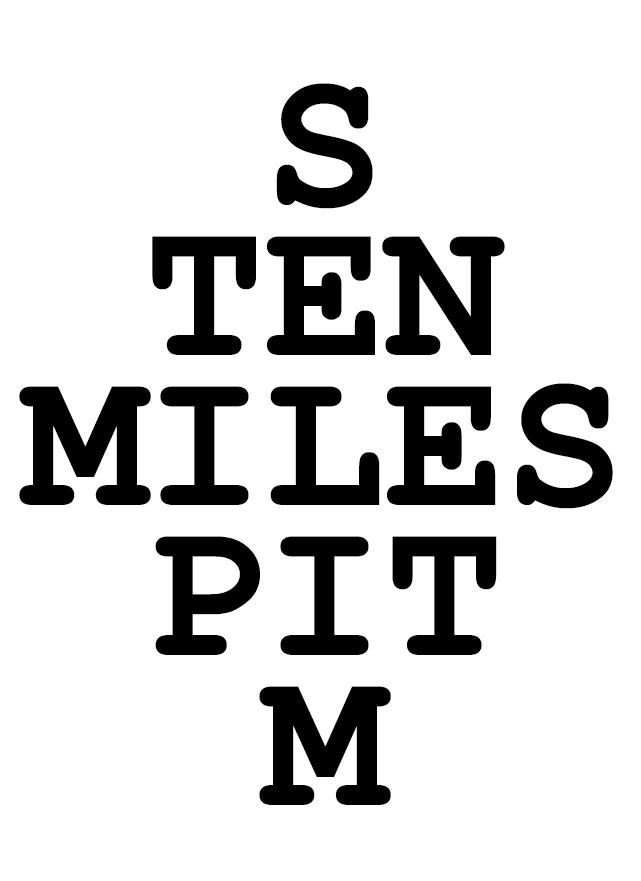

ACROSS, from top to bottom:

1. A consonant. 2. A number. 3. Measures of distance. 4. An abyss. 5. A consonant.

DOWN, from right to left:

1. A consonant. 2. A snare. 3. A name. 4. The point of anything small. 5. A consonant.

You’ll notice the down answers correspond to the across answers in reverse: the “number” is TEN and the “snare” is a NET. You’ll also notice, perhaps, that SELIM is given as “a name.” There were indeed three Turkish sultans named Selim, but the name wasn’t exactly as common as “John” even in Victorian days. But the original Sator square relies on the idea of a farmer named Arepo, so there’s some precedent for using proper names in a crunch.

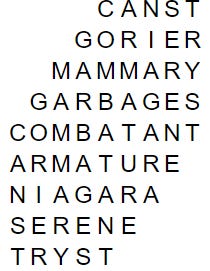

In April 1876, St. Nicholas took another step in the direction of the modern crossword by publishing a double word square. You may have seen such a square more recently in the “mini-crossword” format: here’s one from The Atlantic published last Monday. (Sorry, couldn’t fit in the 1-Across clue, “Person who makes cakes or pies, say.”)

As you can see, it’s a simple word square format, except that the across words and down words are different. You might think such a square would be easier to construct than a traditional word square, since it doesn’t have the added constraint of building one set of words that goes in two directions.

But actually, it’s about as hard to build a 5x5 double word square as it is to build a 6x6 “plain” word square. And that principle holds at any size, a 3x3 double is as hard as a 4x4 regular, a 7x7 double as hard as a regular 8x8. (Mini crosswords almost always include black squares past the 5x5 size.)

Word forms got wilder and weirder in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Recreational grid-makers began to find each other: the first puzzling organizations came into being in the mid-1870s, and by 1883, the Eastern Puzzlers’ League was founded. It became the National Puzzlers’ League and continues to this day.

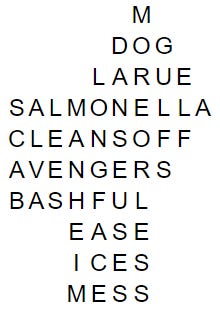

The NPL maintains a few different pages to describe various “forms,” its preferred language for word squares, diamonds, pyramids, et cetera. Some of these forms are “inherently double,” which is to say there’s no way to arrange them so that they read the same across and down. I’ll start getting into such forms in more detail tomorrow.

Surely these forms are crosswords, right? They’re presented in puzzle form and they go across and down. At least the “double” forms like the below one would be, yes?

Not according to the NPL and other cruciverbalist connoisseurs. They’d say that if a form conforms to a known shape, even if that shape seems a bit exotic, then it doesn’t qualify as a crossword, technically. Again, I tend to dissent, but I think there’s one thing both sides can agree on: forms don’t get a lot of study from crossword fans, and vice versa. Tomorrow and the next day, I’ll see if I can correct some of that.