In discussion with my loved ones about anxiety, I often describe it as a living thing—and a malicious one, actively lying to the rest of your brain to grab more territory for itself. Like most living creatures, it’ll do anything to survive.

Inside Out 2 takes a more nuanced view. As David Willis points out in a recent (Patreon-only) strip, every so often, anxiety is telling you the truth about something that should make you anxious—and not in a general the-world’s-on-fire sense, but on a level that could guide you to make better personal decisions.

Inside Out focused on a girl named Riley and the five emotions living in her head. Inside Out 2 introduces some new emotions into the now-teenage Riley’s brain, including a personified Anxiety.

Just as the first Inside Out argues that sadness has an important place in one’s emotional makeup, Anxiety is sometimes helpful to Riley. She certainly wants to protect Riley. But like real anxiety, especially in the modern age, she can take over more and more of Riley’s life, more and more to her detriment, if other feelings don’t hold her in check.

Some viewers, though, felt a little anxious about Anxiety for reasons of continuity. The first Inside Out movie showed everyone’s emotional “office” as a set of five feelings—Joy, Sadness, Disgust, Anger, and Fear. That wasn’t just Riley’s setup, but also her parents’ and others. So what’s with this new schema that includes Anxiety, Embarrassment, Ennui, and Envy (with Nostalgia on the way once characters reach adulthood)?

The movie sort of gets around this question at one point by suggesting that after adolescence, these “secondary, messier” emotions are more like part-timers, only coming into the office when they’re really needed. Mostly, though, it just tries to charm its way past the issue.

Which is all it really can do, because the whole idea that we can reduce our emotions to any number of simple characters is ambitious at best, absurd at worst.

The characters in the original Inside Out movie do map to some simplified models of “primary” emotions. (Scott McCloud’s Making Comics here is discussing expressions, not emotions per se, but his model still holds.)

The emotion excluded from those models is Surprise, presumably because a story has to have novel things happening in it to be interesting, and a guy who went “Wow wow wow!” every time something novel happened would be a one-joke character who’d get old fast.

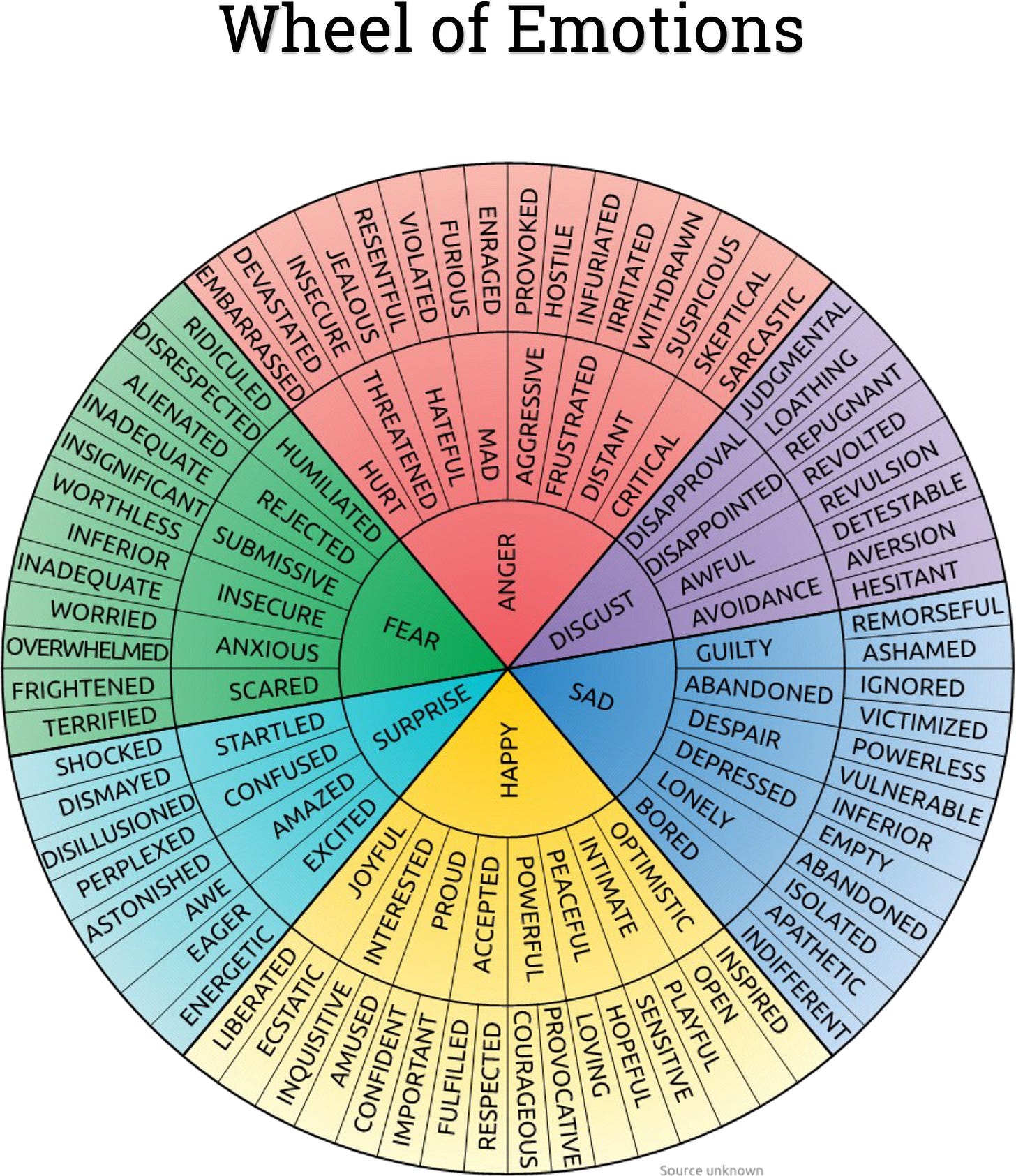

McCloud further suggests that intensifying or combining the basic emotions can give us a lot more nuanced feelings:

Does this method “cover” all the emotions beyond the basic six? Is embarrassment just disgust (aimed inward) mixed with fear and sadness? Is anxiety alertness (defined by McCloud as the mildest kind of surprise) mixed with intense fear? Well, maybe. Some features of the complex emotions seem to break down like that; others don’t, at least to my eye.

Also, since this is a movie about adolescence, isn’t there a really important teenage emotion missing here? Where’s Horniness?

Okay, there are a few answers to that one. One, um, it’s a Disney movie. Two, the story centers on a sports-focused few days where that emotion is unlikely to have much of a role. Three, it’s true that not everyone grows up to experience sexual attraction. But four, it sometimes seems like Disgust acts as the voice of such attraction—an interesting idea, since lust is often the flip side of disgust. But people can experience a mix of disgust and attraction sometimes—augh, it’s complicated.

The Inside Out movies aren’t the first to personify feelings as cartoon characters. For generations, cartoons have used an even more simplified model: tiny angels and devils to speak for characters’ generous and selfish impulses. The first film used a group of five (with a real focus on two), the second uses a group of ten. Would a third attempt fifteen?

Interesting as these schema are, they’re limited. Emotions are messy, and they’ll always be a bit messy—no matter how anxiously we desire to put things in harmonious order.

![[pg004.jpg] [pg004.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F95066dee-613b-49ad-be15-9ecc43a9cf4d_800x1200.jpeg)

![[pg005.jpg] [pg005.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0244a807-70d0-4a66-8cac-51977cc30424_800x1200.jpeg)

![[pg006.jpg] [pg006.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4d0daa5f-d285-403c-9a55-8f8ed4768752_800x1200.jpeg)

![[pg007.jpg] [pg007.jpg]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F388827be-75b2-4985-99c3-ced23f4f0a27_800x1200.jpeg)

I'm pretty sure the movie has a scene where the characters are briefly seen behind the curtain in the adults head, thus "answering" the question.