Goodbye, K.T.

On Nerd Grief

Last month, an old college friend of mine died.

Kellylyn Townsend Hicks, K.T. to her many friends, had had a stroke more than a year ago. I’d followed her situation through mutual friends and her husband Kevin’s occasional updates—seemed like she was on the mend for a while, and then the complications kept piling up, and then she was gone.

She left behind a wonderful daughter, a mourning husband, an enviable creative career (often as Lynn Townsend), and a small army of friends and supporters. There are many in that crowd who I’d consider more qualified to eulogize her than me (link to obit with livestreamed memorial).

The awkward truth is that we hadn’t been close for a while. It happens. People drift apart. But it feels wrong. When I came to college, K.T. was the social center of the Science Fiction Club—and that club, in turn, became the center of my social universe. So it would remain until graduation, and the ripple-effects of my time there are with me even now.

More than any other single person, she showed me how nerds could be social. She ran role-playing games in which seemingly anything could happen. She organized viewing parties for Star Trek: Voyager (in its early, promising days). In fact, almost any big gathering seemed to have K.T. at or near the center of it. She had my mother’s gift for organizing big groups into spaces where everyone felt welcome.

As far as I knew at the time, K.T. and I were the only club members with serious, self-advertised writing ambitions. Almost any science-fiction fan tinkers with writing, but we really wanted to make a go of it. In such a situation, we could’ve been rivals…and since K.T. was far better established in our circle than I was, that would’ve gone poorly for me. Instead, she supported me always, giving her admiration freely.

I left Virginia for the first time to attend graduate school, one of the only schools in the country where I could try to further a comics career. I remember K.T. taking me aside during a shopping mall gathering, asking me about my plans. She gave me eight words as we hugged goodbye:

“I hope you find what you’re looking for.”

I think that’s the best goodbye from a friend I’ve ever gotten.

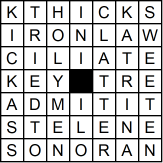

The work I started publishing at that grad school, Fans, owes an obvious debt to that club in general and K.T. in particular. It was a science-fiction adventure about a science-fiction club. I avoided modeling any characters on my friends directly… writers need the freedom to be cruel to their characters, and I’d never have that freedom if I thought of them as my friends.

But bits and pieces found their way in. How could they not? K.T.’s wry wit, her commitment to bringing people together, her straightforward honesty and positive energy… no feature like mine would’ve been worth reading without trying to replicate those things.

It was K.T. and her gatherings that had shown me the truth that the media stereotypes of the time denied. Fans, and even self-identified geeks, weren’t necessarily bookish, repressed introverts. They could support causes, form relationships (and struggle with those like anybody else), sass their day jobs behind their employers’ backs. They could seethe. I could seethe. We could be more than the role the stereotypes assigned us. God knows K.T. was.

Starting Fans gradually put me into another social circle, the circle of webcomics self-publishers. David Willis was one of those, like me. I’ve been his fan, his friend, and his sometime collaborator. To see successful art with a sensibility so close to my own has been a comfort in times of stress and an inspiration in times of activity.

And every once in a while, it’s resonated in some odd way with my own life.

Shortly after K.T.’s death, David finished putting a special comics story online, the last-ever story set in his first fictional universe. And it’s a memorial service.

The grave belongs to Ruth, whose death marked the maturation of David’s early cartooning ambitions. Losing her had repercussions for all his other then-major characters and one whom we hadn’t even seen yet. In this tale, set fifteen years later, those people gather and remember not her death, but how she affected them in life.

But their depths of connection to Ruth are not equal. One is her brother, who owes her his self-esteem. Two others knew her when they were kids; the other three met her in college. Four remember moments of great insight from her; the other two recall how they handled it when they found her at her most vulnerable. (Poorly, mostly.) One was her lover for all of an hour. One had a link to her it’s hard to fully define. But others never really got as close as they might have, and only came to see her insights for what they were after she passed.

This may be how nerds grieve. Like anyone else, we deal with the undiscovered country of death by trying to build bridges between it and what we find familiar. I found some comfort in the scene of uth’s mourners standing together, despite the inequality of their connections to the deceased. What they feel is what matters.

I still feel like I belong in the back of the mourners’ line for K.T.—her family, her ex, and others who maintained closer ties are the ones who should be giving funereal speeches. But brief as our key moments were, they had meaning to me. They are evidence of the range of the lives she touched, the ease with which she did.

None of my work would exist without the key kindnesses paid me by people like David Willis and K.T. Hicks. My whole life would be different and worse.

I hope K.T. found what she was looking for.

From my vantage point, she seemed to.