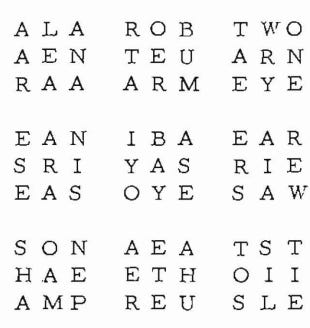

A while back, I discussed word forms, starting with this square:

Many other shapes were considered, but all of them were in two dimensions. Is it possible to construct a word cube? What about a fourth- or even fifth-dimensional structure?

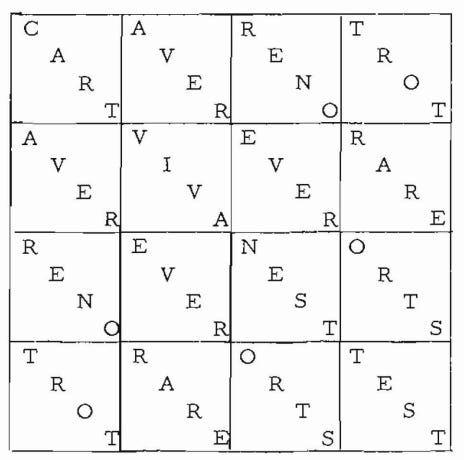

Here’s a “regular” cube structure by Darryl Francis from Word Ways #4.3, 1971. You “read” it in three directions: across, down, and diagonally within the smallest squares. But you can read the top-left letters in each small square across and down, and the same for the bottom-right letters and the other two positions.

Note that this cube’s “top level” is a word square (CART-AVER-RENO-TROT), followed by another three on lower levels (AVER-VIVA-EVER-RARE, RENO-EVER-NEST-ORTS, TROT-RARE-ORTS-TEST). Most words appear in six different directions in this cube, while the four along the top layer’s diagonal axis—CART, VIVA, NEST, and TEST—appear “only” three times.

Can one make a “triple” word cube, with different words in each direction? Apparently:

This cube contains 48 different four-letter words—all of them viable.

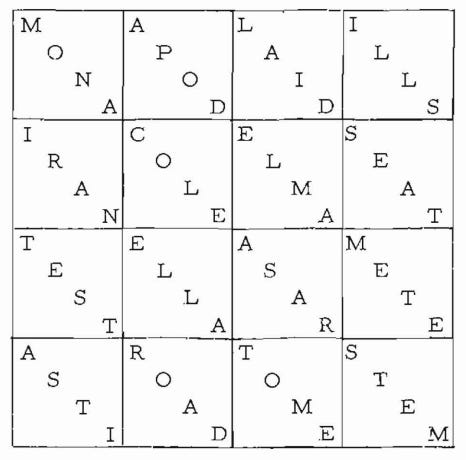

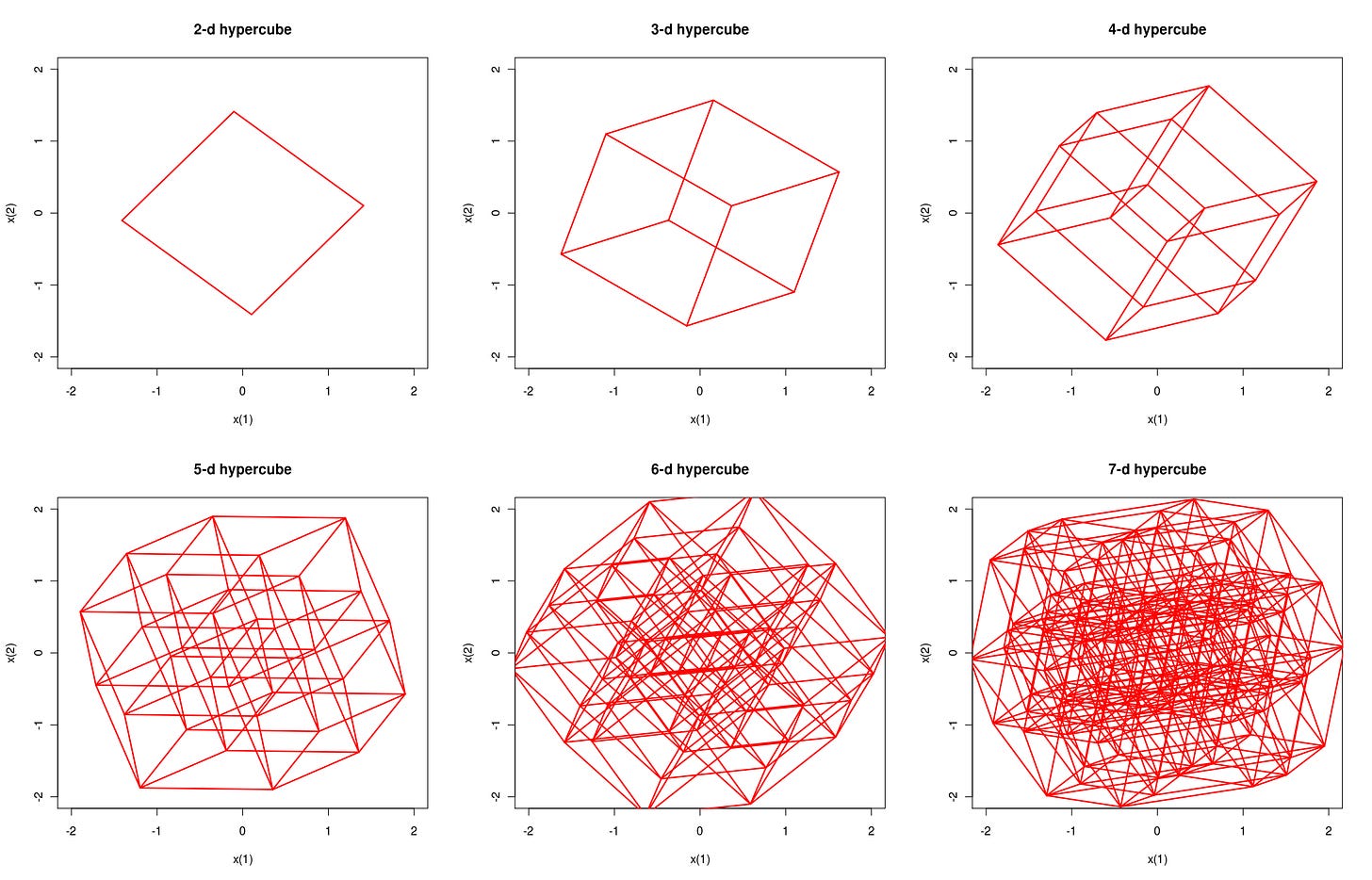

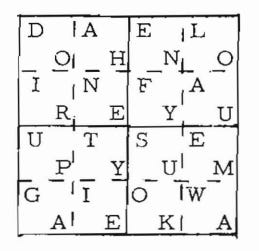

Higher-dimensional forms are hard to visualize, since they’re not part of our everyday experience. We don’t even have great names for them. The four-dimensional analogue to a square or cube is known as a tesseract or hypercube or 4-D hypercube, five-dimensional is a hyperhypercube or a 5-D hypercube, as below, and after that one just keeps adding numbers. I guess we could speak of hyperhyperhyperhyperhyperhypercubes, but why would we?

Instead of doing a “simple” 4-D hypercube, Darryl jumped right to the complex version, the one with all different words, though to do so, he did scale things down to three-letter words and some of those three-letter words were more challenging, big-dictionary fare. What you see below looks at first like nine double word squares:

ALA, AEN, RAA, AAR, LEA, and ANA were all legitimate words, if somewhat obscure, and the same applies to the other eight word squares, for a total of 54 words.

But this is only half the story. To get to the other two dimensions, pick one position in one of the word squares and compare it to the same position in the other eight. The upper left corner of the first word square is A, followed by R in the same spot in the second word square, then T, E, I, E, S, A, and T. This gives us ART, EIE, SAT, AES, RIA, and TET. (EIE is an old spelling of “eye,” AES is sometimes used as the plural of the letter A.) Do this for the other eight positions and you’ll end up with another 54 words, for a total of 108.

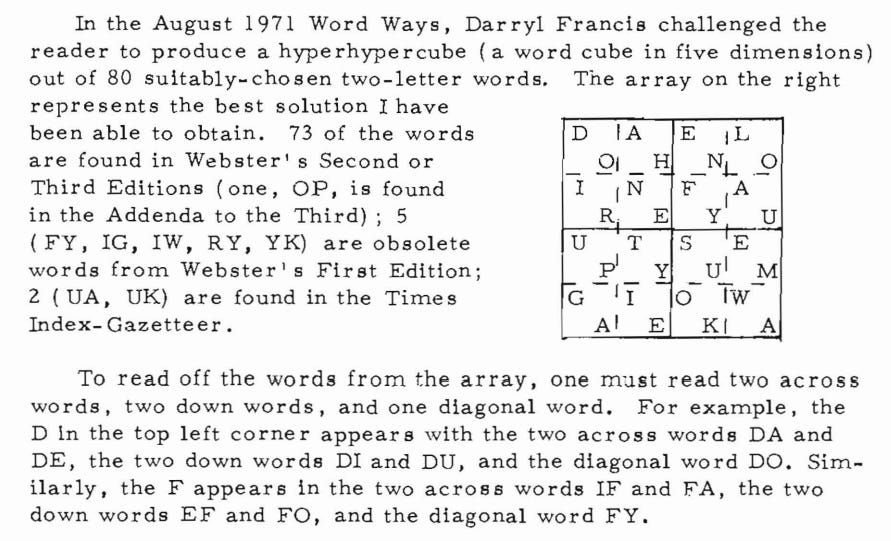

In Word Ways #4.4, Delphi Knoxjaqzonville submitted “A Hyperhypercube of Side Two.” If you have trouble parsing this one as well, I’ve included her explanation below.

As you can see, the basic grid of starting letters is 4x4—with each row and column representing two words, not just one. Multiplying that by the five dimensions of the hyperhypercube results in 80 different words.

As in the hypercube sample: a few of these words are obscure, and it’s unlikely anyone could get better results using common dictionary words today. However, modern crosswords permit the use of familiar initialisms—MDs, FYI, and such. Opening these high-level forms up to that vocabulary might produce worthwhile results. Still wouldn’t want to try it myself, though—not without software!