Mickey Mouse Operations

Journey to the public domain.

As you may have heard, Mickey Mouse joined the public domain at the start of this year. Sort of. Kind of. Sorta kinda.

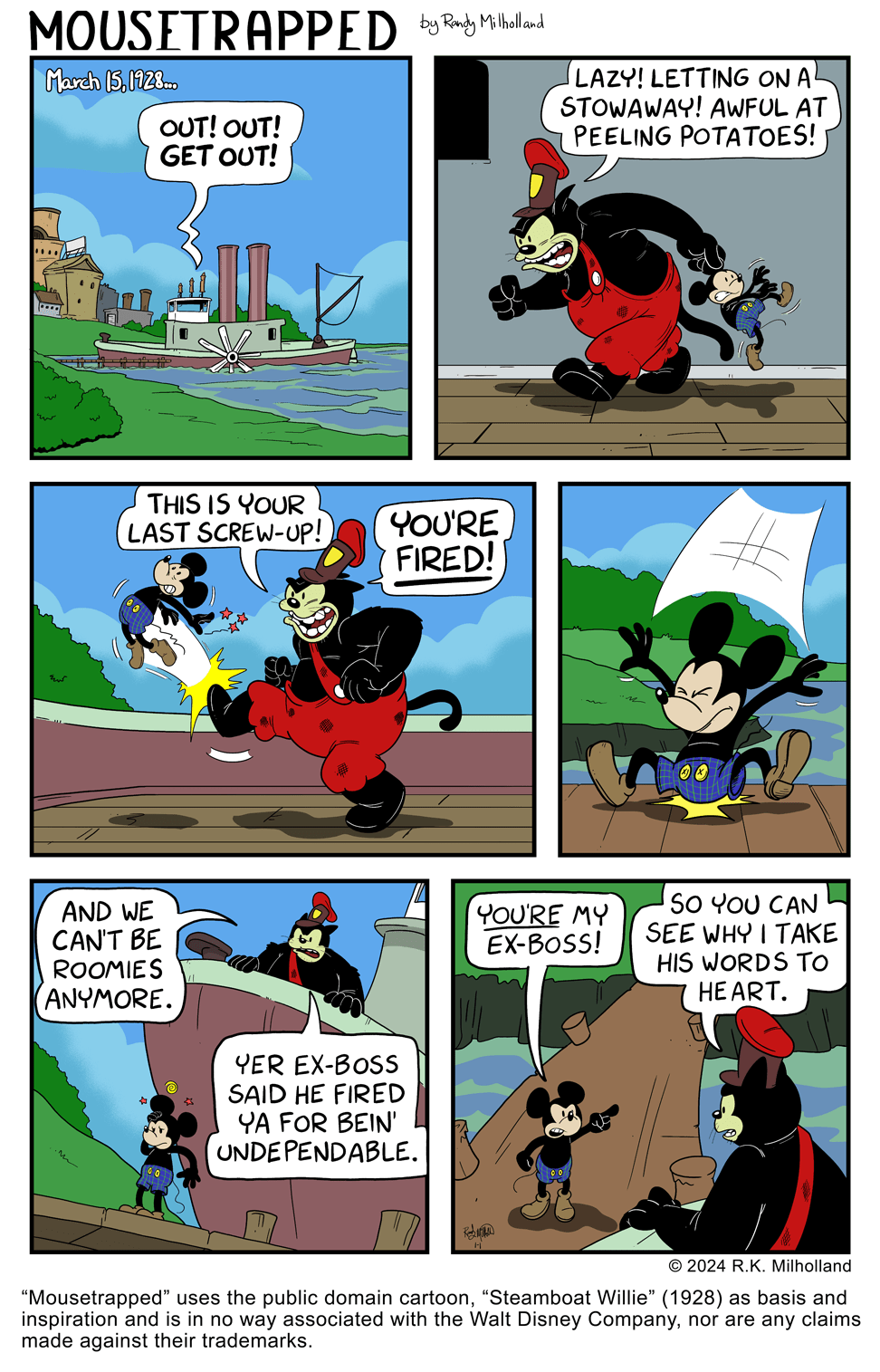

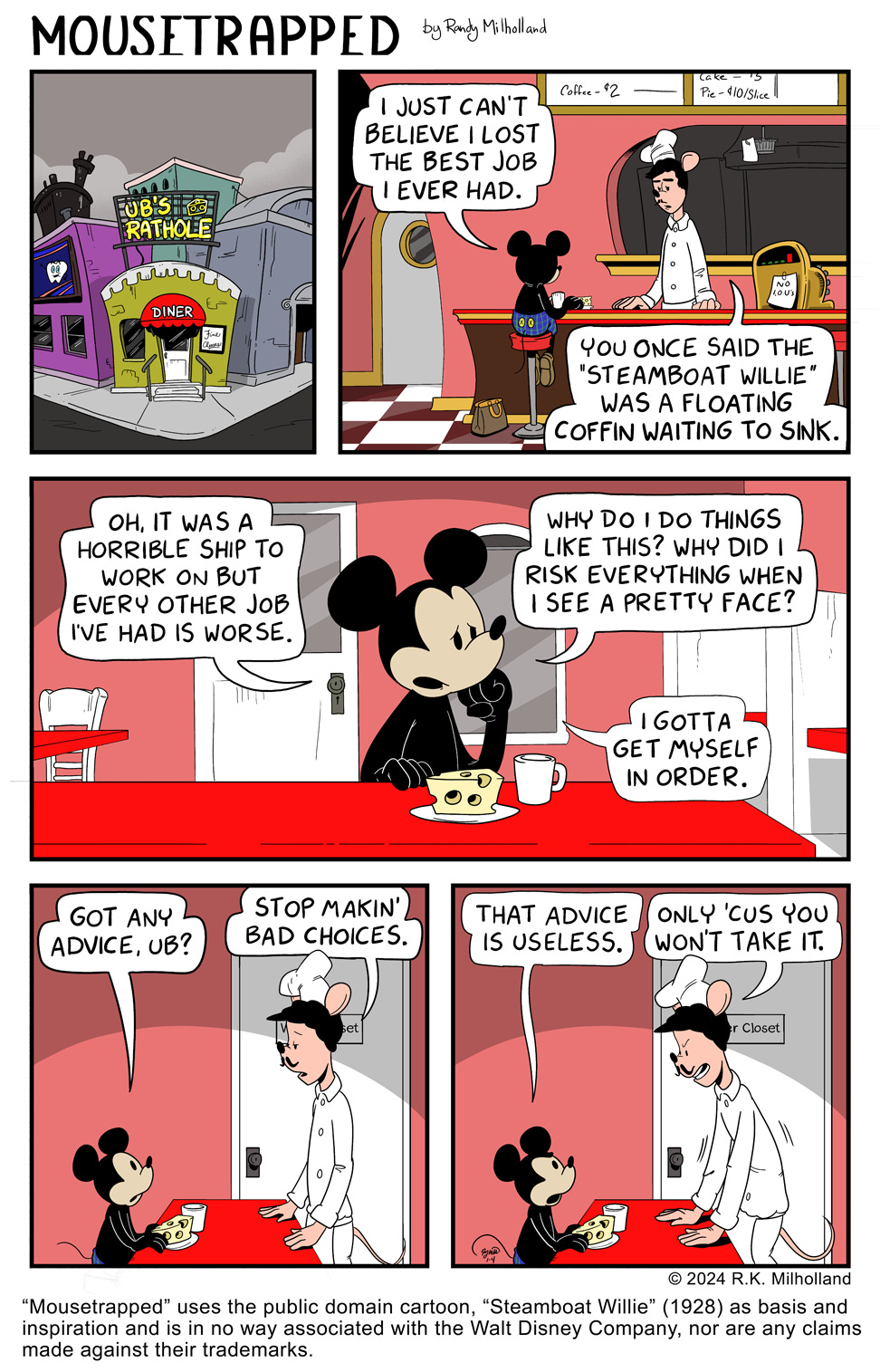

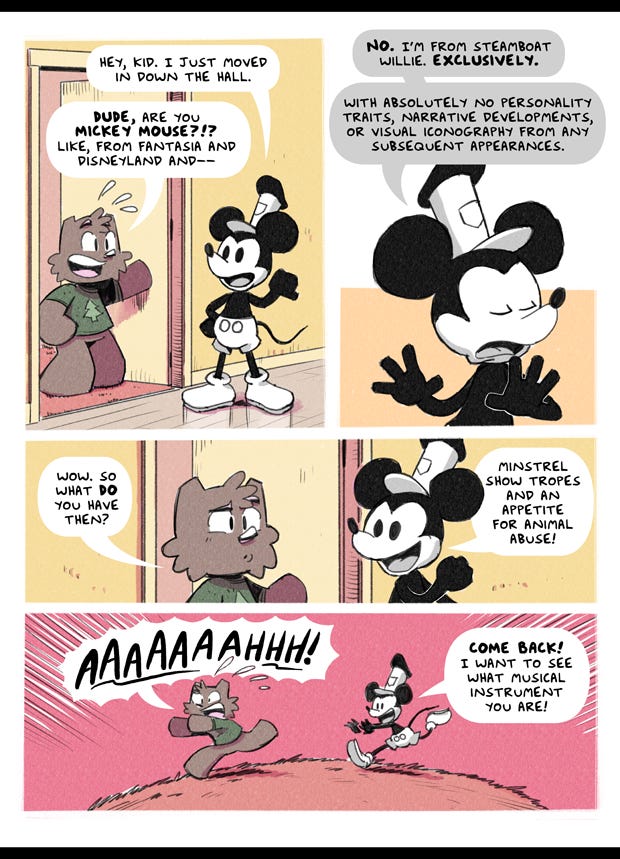

What went into public domain was Steamboat Willie, the first Mickey Mouse cartoon. It was a sensation at the time of its release in 1928, and the fluid style of animation is still a delight to the eye. Some aspects of Mickey, his girlfriend Minnie, and his nemesis Pete are visible in rough-draft form: the boyish delight Mickey takes in life, the way he’ll drop everything to help Minnie, and Pete’s general air of overbearing menace and exploitable stupidity.

But it’s hardly the Mickey we know today. This Mickey chafes at authority, is quick to revenge, and spends the climax of the short as a one-man band using various animals as musical instruments, sometimes against their will. Rather than a scheming bully or villain, Pete is his fed-up boss…and it’s not hard to see why he’s fed up, what with all the time Mickey spends commandeering the steering wheel, bringing on a stowaway, and messing with animals that are presumably cargo.

Nothing that’s been added to Mickey since then—not his voice, not Minnie or Pete’s names, not the color of his pants—is yet in the public domain. Still, a number of cartoonists have already moved in on what is there—including two old friends I follow from my webcomics days, Randy Milholland (with Mousetrapped) and Sam Logan (with a limited storyline in his Sam and Fuzzy).

Of course, indie artists haven’t always waited for permission. Sometimes using the character in ways not “permitted” is the whole point, an act of defiance against the system.

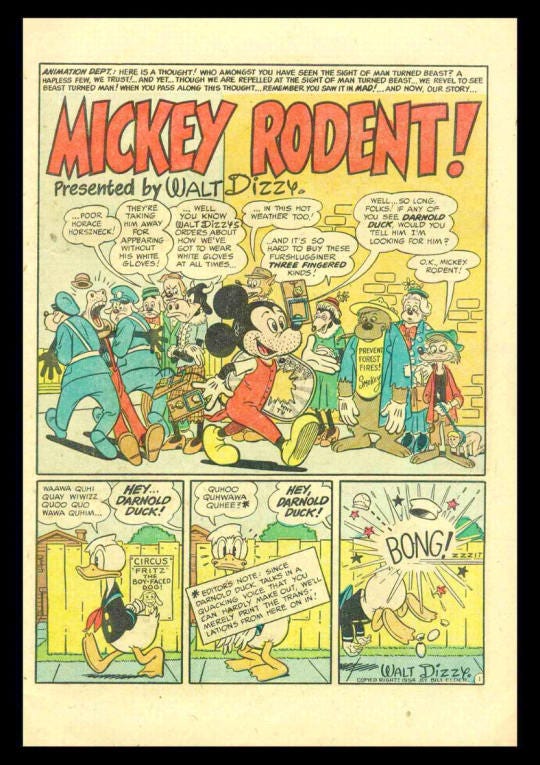

Other usages have split the difference. One popular technique is to change the copyrighted character just enough to be legally defensible, but still keep close enough to the source material that most readers can’t help but recognize what you’re doing. MAD Magazine pointed the way to this kind of parody back in the 1950s—usually calling its parodies “satires,” the better to align with the legal term “satiric intent.”

Permitted or not, not every subversive “reuse” of a character is a good idea. Winnie the Pooh entered the public domain two years ago, resulting in the low-budget gorefest Winnie the Pooh: Blood and Honey, with a Rotten Tomatoes score of 3%. It has little to offer but the s(c)h(l)ock value of turning beloved children’s characters into Five Nights at Freddy’s-style monsters. A similar treatment of Mickey Mouse—albeit an impostor instead of the “real” Mickey—already exists as a Roblox game.

No offense to horror fans, but these cheapjack, unimaginative works are almost enough to make one think twice about the whole “public domain” idea.

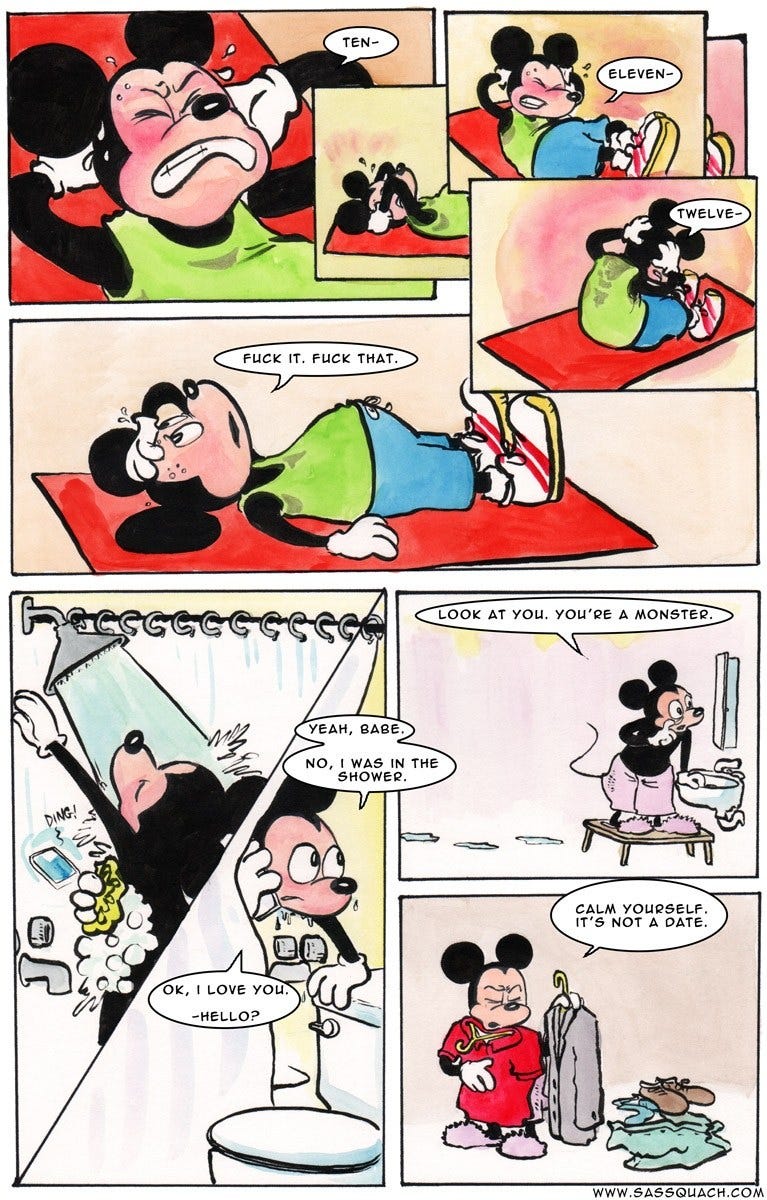

But the best “Mickey Mouse treatment” I’ve seen was “Boys’ Night,” created a decade ago by filmmaker Max Landis and indie cartoonist Ashley Quach/Perryman. You can read it here. Landis and Quach’s Mickey, Donald, and Goofy are middle-aged, settled, and trying to enjoy themselves while questions about their life’s meaning hover, usually just out of view.

The story’s sometimes renamed “Mickey’s Midlife Crisis,” but I think that’s too reductive—Mickey might reach the edge of such a crisis, but the rewards and concerns of everyday life keep pulling him back. Landis and Quach didn’t have a public-domain blessing to play with these toys, but thank goodness they were foolish enough to ignore that. “Boys’ Night” had something to say that was worth the risk.

As it happens, I had to confront a similar issue of “toy-stealing” a few times in my career. But more about that tomorrow.