The original meaning of “apostrophe” was essentially “TMW the speaker addresses someone who can’t talk back.” The addressee could be a creature, place, or thing who could never speak or a person who’s comatose, dead, or merely absent. Examples include “Wherefore art thou Romeo?”—even though Romeo is eavesdropping on her, Juliet thinks she’s just talking to herself, so it counts. Another example: Tom Hanks’ character in Cast Away spends a lot of it talking to Wilson, a volleyball with a face painted on it.

In its earliest days, the apostrophe-as-punctuation signaled the use of apostrophe-as-literary-device. For old time’s sake, I’ll use it now:

’Hey, John McWhorter! Calm down and stop defending willful ignorance!

New York Times columnist McWhorter is no fan of the apostrophe. He’s had enough of people shaming homemade birthday cards that say, “Its your birthday—your 17!” In fact, he’s ready to shame the shamers:

Why does the issue of apostrophes elicit rage?…I suggest that the visceral sentiment in this case is actually a kind of classism—one from which I cannot honestly exempt myself. When we no longer talk (at least overtly) of people marrying “beneath” themselves, when the difference in dress style between the rich and the poor is much less stark than it was in the past, when popular entertainment is no longer considered the province of “the lower orders,” blackboard grammar rules provide one of last permissible ways to look down on others.

I don’t know how much time Mr. McWhorter spends online, but I’m guessing “not a lot.” Outside the genteel halls of academia, there are a bunch of accepted ways to make fun of people, class-based and otherwise. And never learning the it’s/its distinction doesn’t just mean you couldn’t afford a prep school, it means you never had the curiosity to learn the underlying rules.

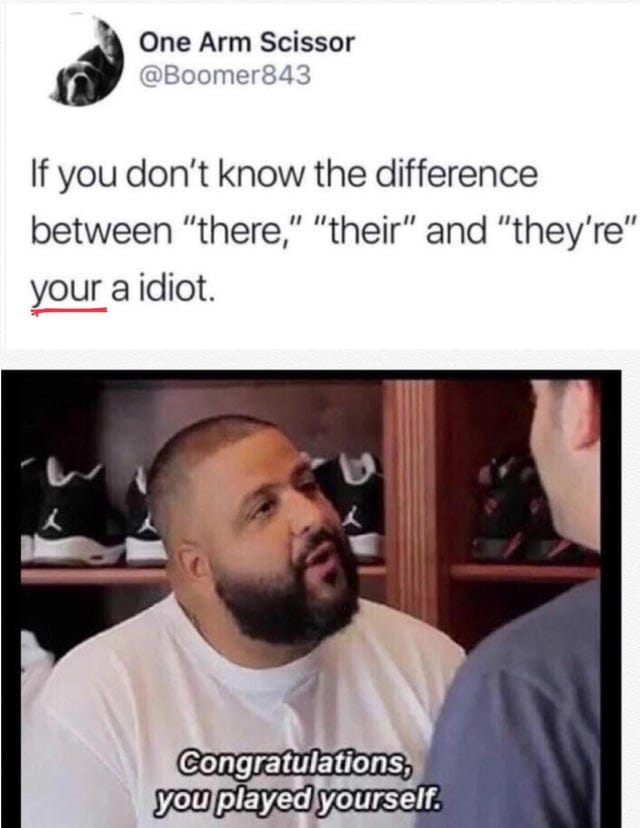

I feel such incuriosity is a fairer target than poverty—especially online, where it’s not clear who’s 17 and who’s 70, who’s just misinformed and who’s a bot. Word choice is sometimes our only basis for deciding whether someone’s worth listening to. Clues like “your an idiot” make that decision easier.

That said, almost everybody mixes up “its” and “it’s” at some point, even if they correct themselves a second later. Its/it’s—and your/you’re, and their/they’re—can fool the ear as homophones, so think about them with the eye.

Possessive pronouns—my, your, his, her, its, their, mine, yours, hers, and theirs—do not use apostrophes. Possessive noun phrases—the cat’s, the dog’s, the pets’—do (with the apostrophe trailing the s in plurals). Contractions—I’m, you’re, he’s, she’s, it’s, they’re—use apostrophes to mark where “missing” letters would be.

There are no overlaps between these three types. It’s isn’t a possessive, because it and its are pronouns, and pronouns never use apostrophes.

Now, sure, there are problems. The apostrophe-s serves as both a contracted “is” and a sign of possession. In phrases like the farmer’s orange, it could be either one. Style guides disagree over “the boss’s” vs. “the boss’,” and “J’s” vs. “Js” as plurals of J.

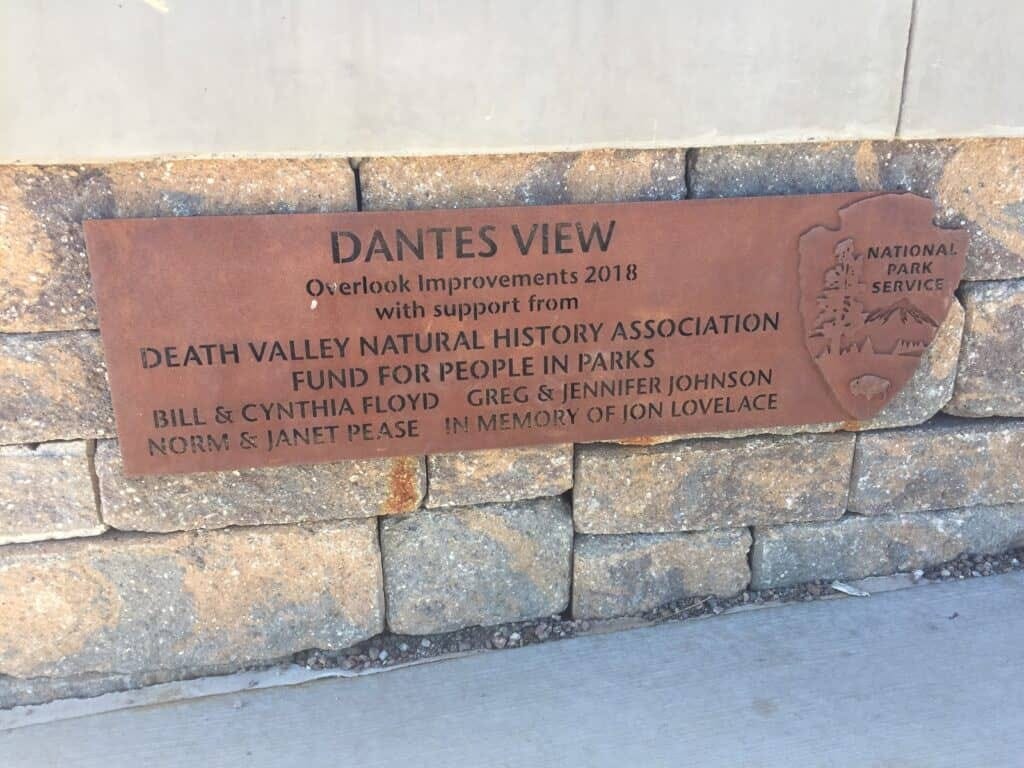

McWhorter also brings up apostrophe-free street signs like “St. Marys”—though that’s a much older practice than he implies. Since its beginnings in 1890, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names has removed apostrophes in place names. Officially, it’s “Dantes View,” not “Dante’s View.” It’s only acknowledged five exceptions, among them “Martha’s Vineyard.”

What jeopardizes the apostrophe’s future, though, is a more technical issue. The apostrophe sign also serves as a single quote—and quote marks, single and double, can mess with computer code, which underlies a lot of modern communication.

When I was writing alt texts for the images in the Guilded Age webcomic, I had to use single quotes in place of double quotes. Programmers sometimes find their code runs into errors if their text contains a simple contraction. There are workarounds—HTML has '—but it’s often easier to just avoid apostrophes than remember those.

Whatever else you can say about AI, it deserves credit for accommodating this feature of human speech and bypassing any glitches it might’ve caused. But if the next generation of AI developers keeps prizing efficiency over tradition, apostrophe use might be one of many things to get disrupted. We might complain to our technology about this—but much like Wilson the volleyball, it won’t exactly have a consciousness with which to reply.

On the other hand, that could mean the absence of apostrophes could still help us decide what writing isn’t worth reading. So there’s that.

Possessive pronouns used by politicians:

HI$. HER$ THEIR$. OUR$$$ YOURs ONE$