In case you missed it, once-universally-beloved sci-fi, fantasy, and comics author Neil Gaiman is at the center of scandal for sexual abuse. I’m convinced by the New York/Vulture case against him (and his own feeble defense), and I’m not here to argue it. I’m here to think over the fallout.

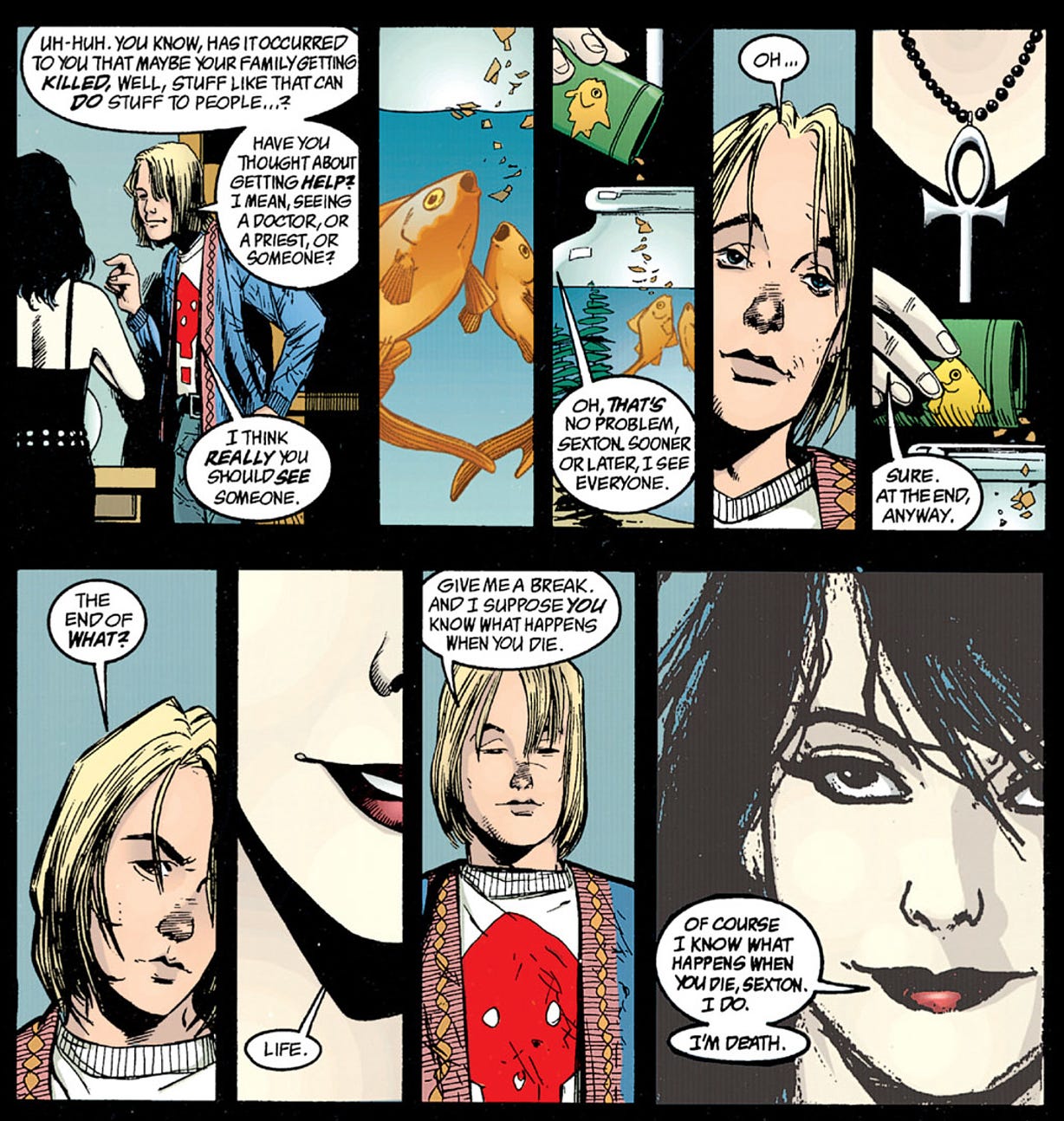

For me, Neil Gaiman’s work is forever associated with a moment in my high school where I saw a few cute, younger girls passing around Death: The High Cost of Living in study period—including my then kinda-sorta girlfriend. “Cute girls” and “comics” didn’t really go together for my generation, so it was clear Gaiman understood things about 1990s culture that most of his contemporaries didn’t.

I can’t help but think of them now. If I’d known how Gaiman would turn out, I don’t think I’d choose to tell them. It’d be too cruel at that point in their lives.

We’re a bit more jaded now. Even science-fiction fandom has been here often enough. Joss Whedon? Isaac Asimov, Julius Schwartz, Mercedes Lackey? Those are just the first creatives who come to mind whose private behavior betrays the values expressed in their public work. And that’s not counting fan-faves who’ve found more public ways to be ugh, like J.K. Rowling, Orson Scott Card—the list goes on. (Is Woody Allen one of “ours”?)

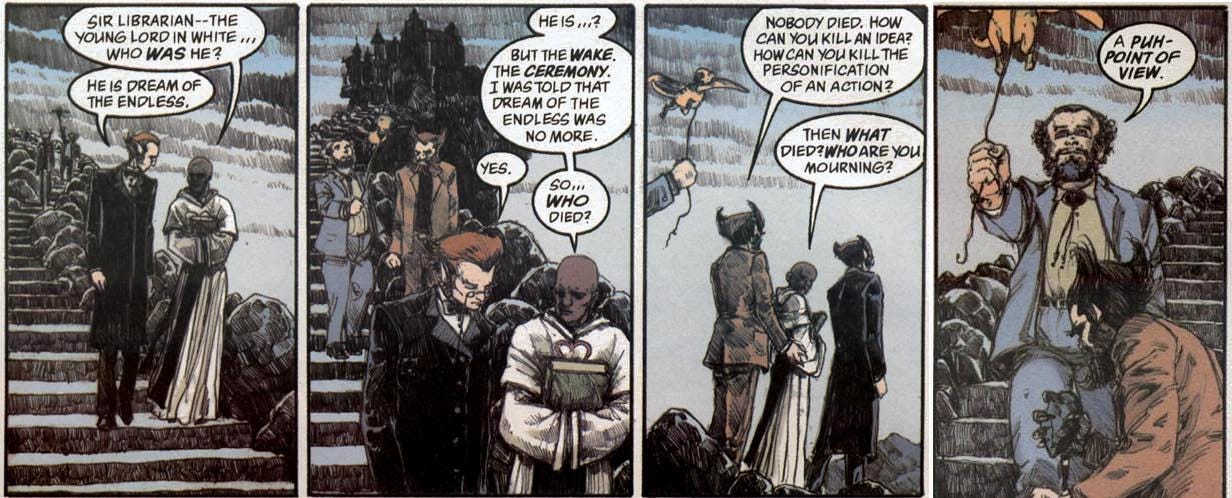

The Vulture piece mentions the Sandman story of author Richard Madoc, who keeps the Muse Calliope in sexual slavery. When the Sandman catches up with Madoc, he punishes Madoc with great creativity. Literally.

Only Calliope’s intercession saves Madoc from permanent madness.

Of the accusations against Gaiman, only the mildest one springs from the period he was writing Sandman. Richard Madoc may not have been a confession of his sins so much as a warning from his subconscious. If so, he failed to heed it.

But this kind of retroactive analysis has dangers. It ties into the most radical “codebreaker” theory of literature, the idea that the writer encodes all of themselves into the writing, and that critics—or intelligent readers—can decode the messages. Surprised Gaiman was (or became) abusive? Well, it’s your fault for not reading the Calliope story correctly! [Sarcastic rim shot.]

But that’s not how it works. Oh, writers use their experiences and interests as inspiration, sure. Sometimes they’ll reveal more than they intend, sure. But no fiction is pure self-confession, and if you try to stare such confessions out of it, you’ll end up fooling yourself.

Case in point! Sandman was well ahead of its time in LGBTQ representation, as was Gaiman’s 1980s work on Miracleman. So, for literal years, I believed Gaiman was sending us the coded message…that he was gay. What if “Neil Gaiman” was a pen name? Sounded plausible to me!

Some online discussion recommends doing the opposite of such analysis: separating the art from the artist. I’m uneasy with that term in the age of AI art. But it’s possible to read Gaiman’s work without thinking much about Gaiman the person. I reread some of Sandman for this piece, and I found it like slipping into comfortable old shoes. I don’t regret watching Stardust or Coraline. I doubt I’ll check out any new Gaiman, but I don’t feel like I couldn’t.

One reason I’m chill about my side of the experience is, I had my “Neil Gaiman crisis” in the late 1990s. Peter David, one of my favorite writers then—announced he was getting a divorce.

Not a comparable offense! But I was a young writer, hungry for role models. There were others whose writing I admired more, but here was a writer who advertised himself as the kind of person I wanted to be. Until he couldn’t. (David’s had other controversies since, but those aren’t relevant.)

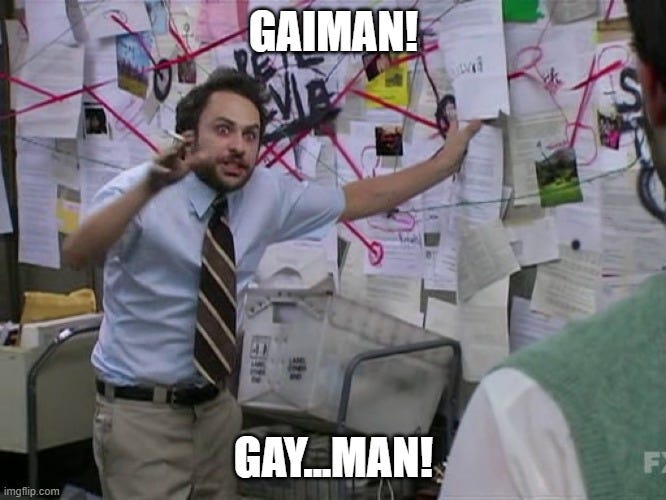

So what did I do? Well, I mentioned writers use their experiences as inspiration, right? It’s cheaper than therapy!

(Excuse me while I try to limit my cringe at my early writing and Rumy’s deal at this stage. There are beliefs readers could form about me through my work, too.)

Of course, it’s easy to poke fun at Rumy and me for not realizing artists are human. Gaiman’s crimes are more severe than “being human”: his victims deserve attention.

Some will urge erasure of Gaiman’s work in sympathy to those victims—but that’s a road I don’t want to go down. Guarding our small comforts is important. Without them, we become anxious, bitter, and less able to comfort others, including victims of abuse we encounter in our lives. Some days [glances at the calendar], the comforts are extra necessary.

Not everyone will continue to find Gaiman’s stories a comfort at all. For some of them, their parasocial relationship with him was key to the reading experience. I sympathize but hope they can move past the hurt and on to other authors.

One of my small comforts is knowing that great writing can come from great people, flawed individuals, or even damaged, abusive gnomes. It gives me hope the things I produce can rise about my imperfections. If there’s any coded “message” I find in Sandman, it’s that many dreams—the ones worth remembering—outshine their dreamers.

Next: A crossword from an author whose name is new to me! I’ll try not to idolize him too much.

Thank you