As I said yesterday, super-teams had a quiet period in the 1950s before coming back into fashion around 1960. But while DC’s followed the jolly let’s-all-get-along model, Marvel’s had more interpersonal drama than Jersey Shore.

Close on the Fantastic Four’s heels came the Avengers. Unlike the Four, but like the JLA and JSA, the Avengers were a team of all-stars—four of its five original members had already headlined their own features.

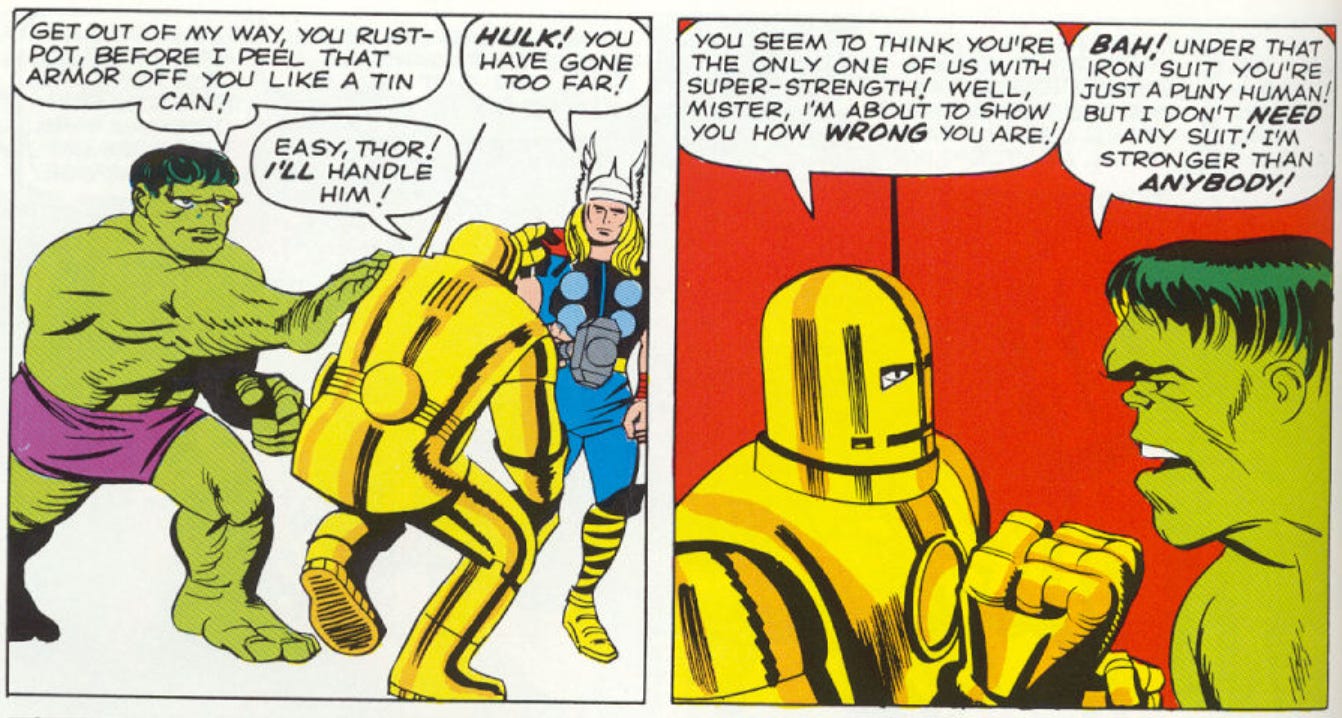

But one of those five was the Hulk. You can guess how that worked out. (The Hulk shown below is an impostor, but he acts so much like the real one that it makes no difference. Avengers #2.)

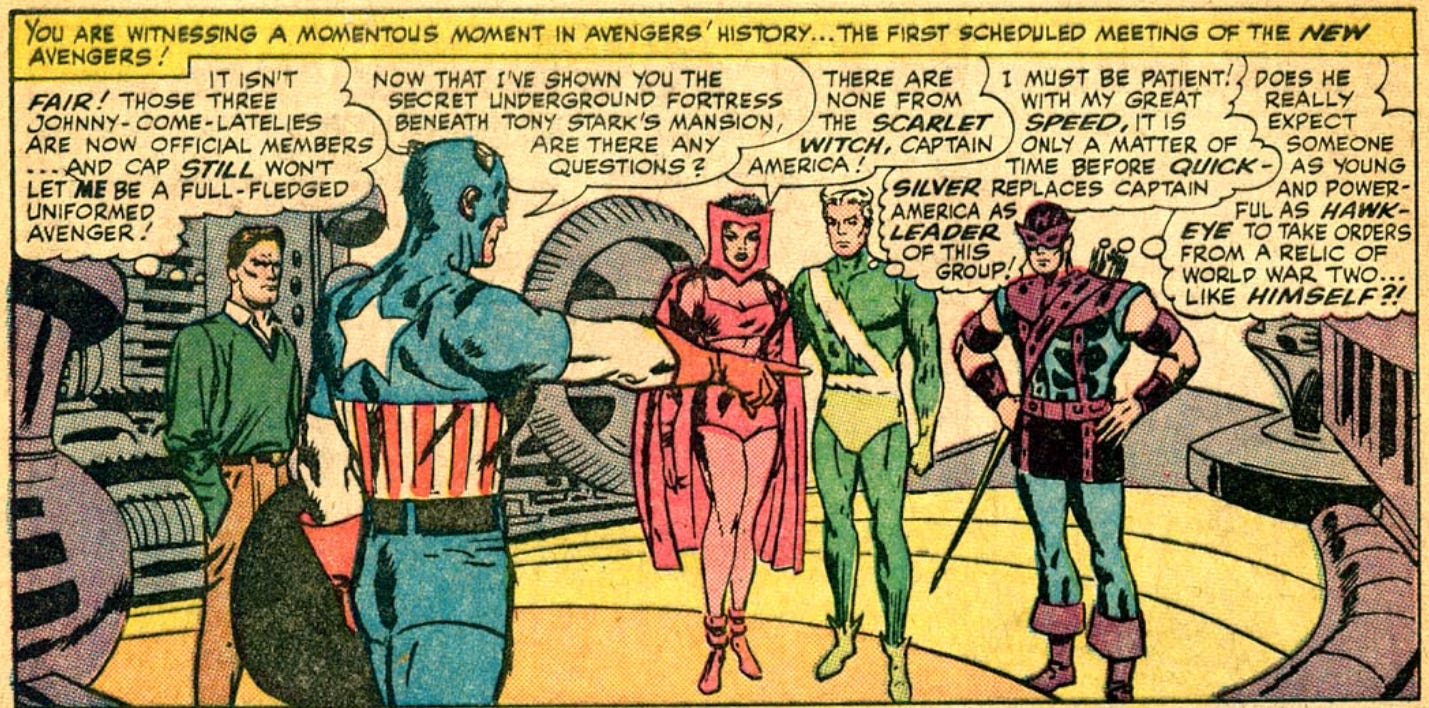

Lee and Kirby had to cool the fires just a little bit after that—the Fantastic Four became more of a family, and the Avengers at least started fighting villains more often than they fought each other. Still, the second wave of Avengers included three just-reformed super-criminals, two of whom were arrogant jerks (#17).

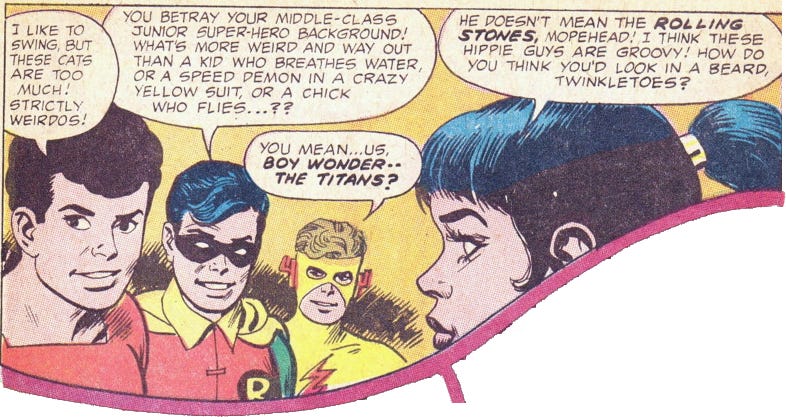

In 1963, Marvel came out with the X-Men; in 1964, DC introduced the Teen Titans. One represented a persecuted minority; the other was a group of superhero nepo babies. No question which was going to have a harder time. It took a while for X-Men to catch on, but its themes of alienation proved more durable than Teen Titans’ “cool, with-it” dialogue (X-Men #15 vs. Teen Titans #15).

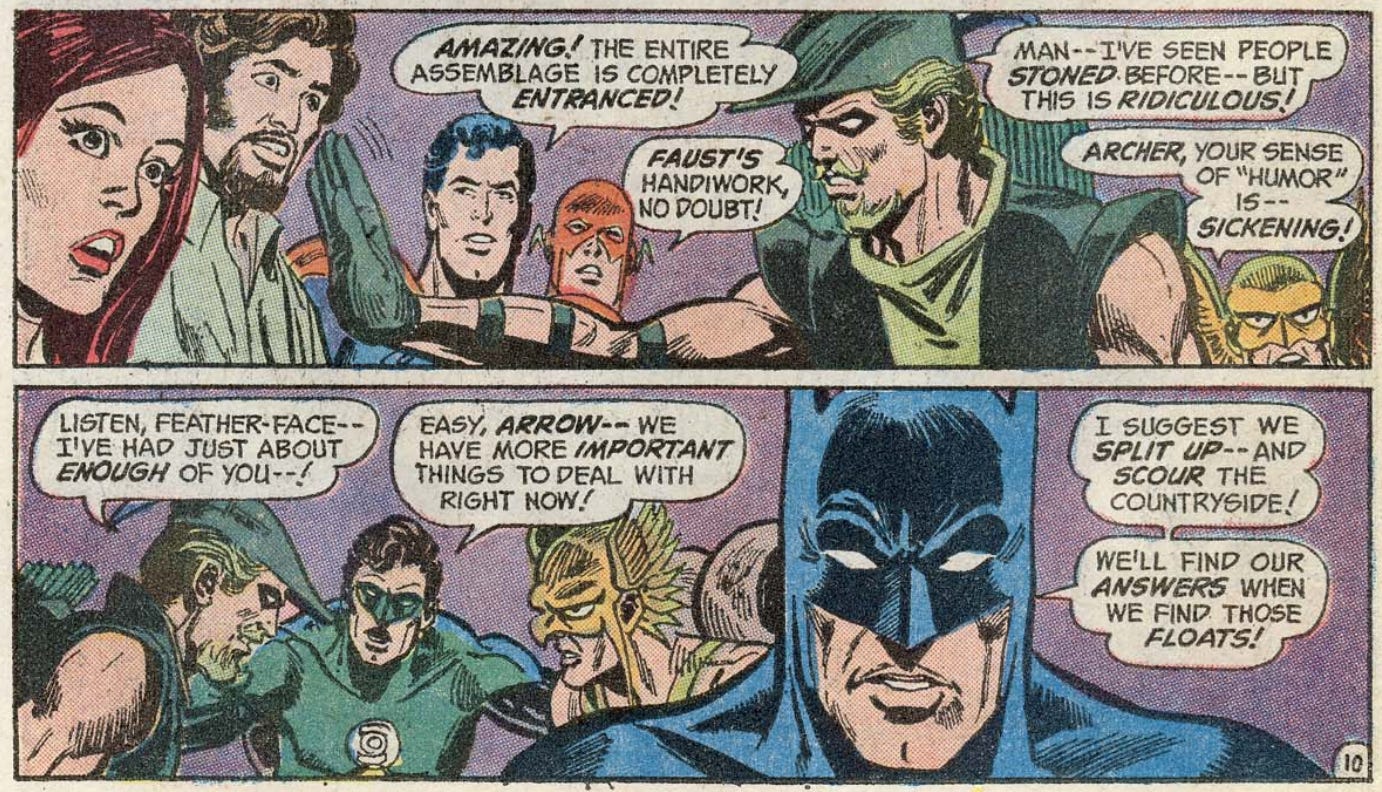

Success breeds imitation, and Marvel and DC have spent most of their histories copying off each other’s homework. By the 1970s, DC started getting interested in this “intrateam conflict” thing, though for a long while, the JLA’s only source of such conflict seemed to be Green Arrow and sometimes Hawkman (Justice League of America #103).

In some later periods, DC embraced hero-hero conflict even more than Marvel had. The cinematic Avengers may have fought a civil war, but at least Marvel didn’t do a whole movie about one of their two biggest heroes plotting to kill the other like Batman vs. Superman. Hurray for the “world’s finest team”!

Batman and Superman do resolve their differences in the film, long enough to save the world through unity and sacrifice. In another of DC’s super-team stories, sometimes called the genre’s greatest literary achievement, hero team-ups don’t even manage that much.

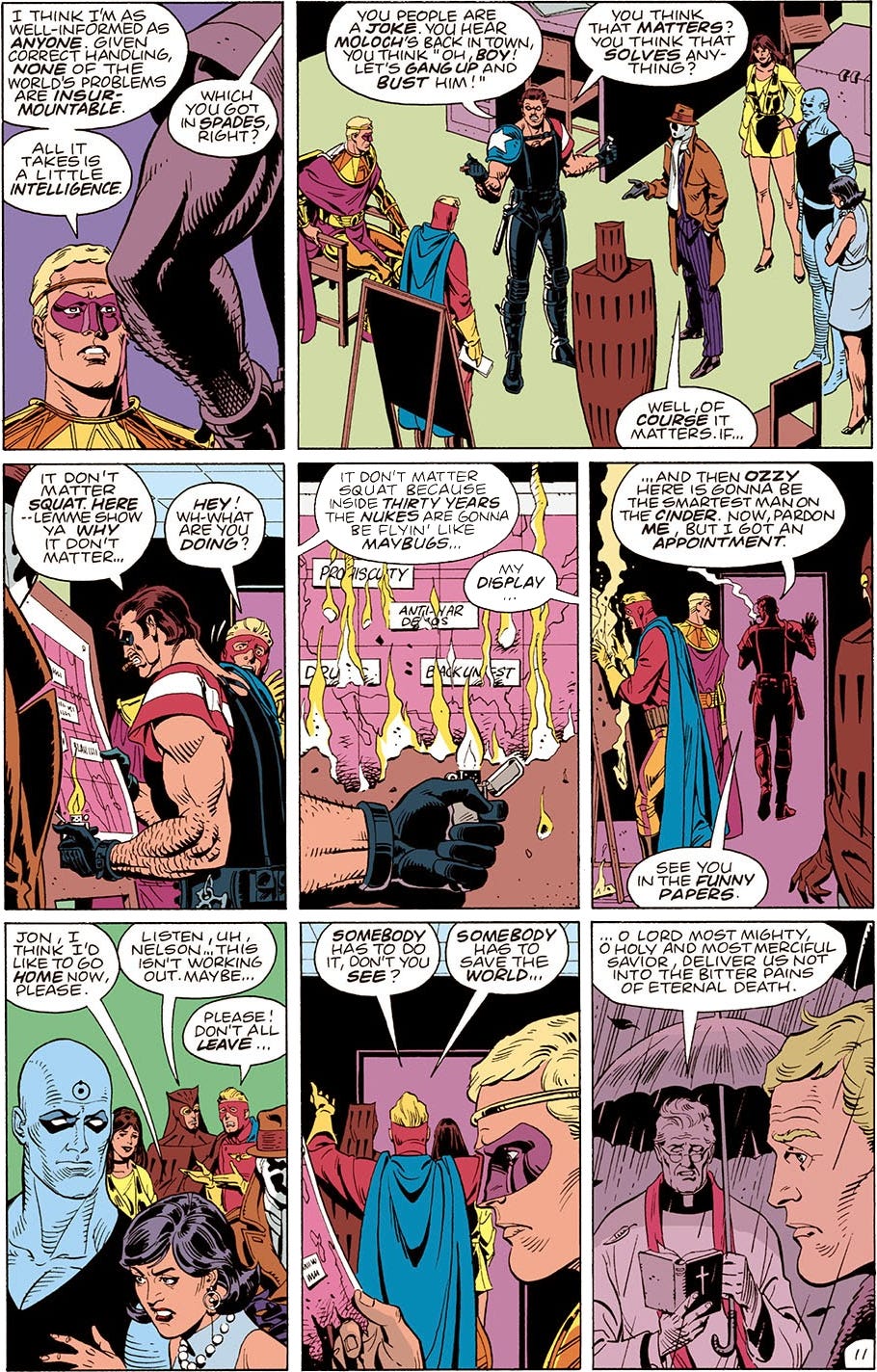

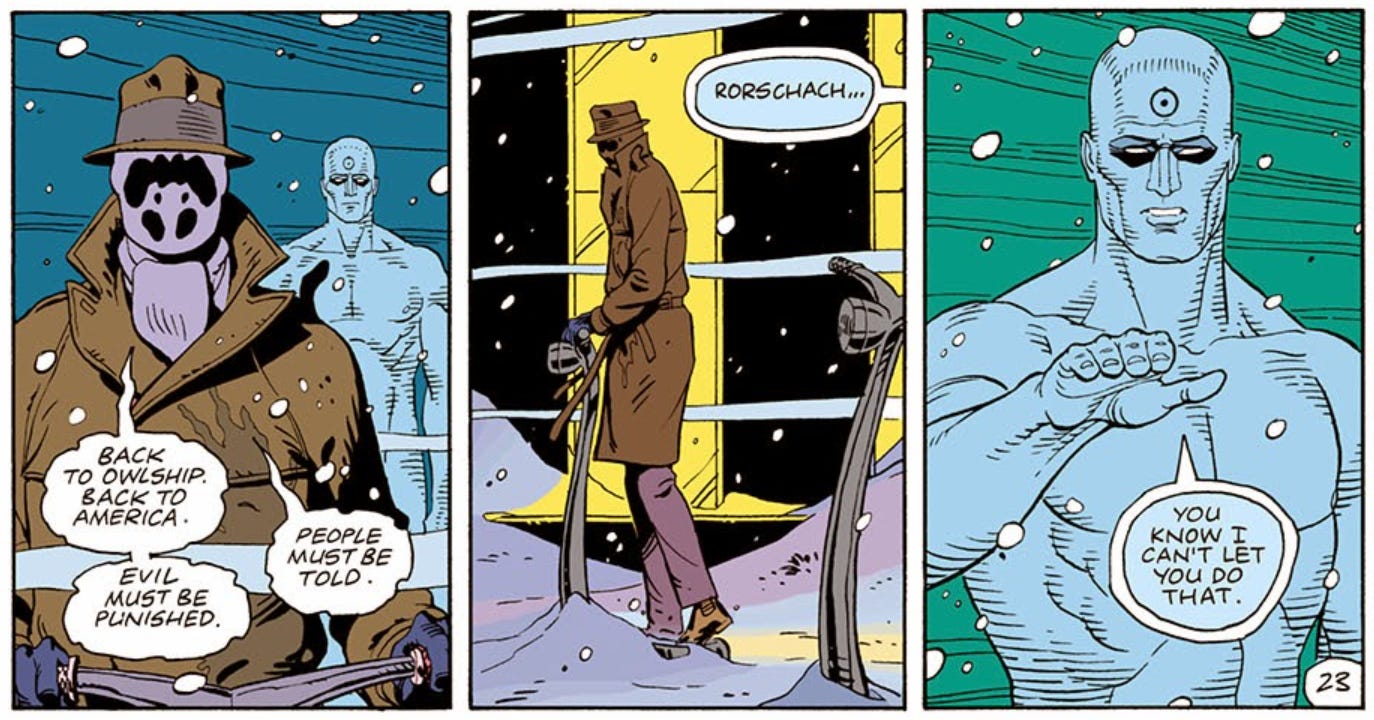

Watchmen is an ironic title—there’s no super-team called the Watchmen. Spanning about fifty years, the story shows two attempts to form such a group—but the 1940s Minutemen are mostly a publicity stunt, and the 1960s Crimebusters fall apart during their first meeting.

By the 1980s, fundamental disagreements on what it means to “save the world” lead to two hero-on-hero murders, at the story’s beginning and climax. Some heroes unite for a while, but in the end, this achieves almost nothing. No hope for a Justice Society here. Not much hope for small-s society, either.

Grim stuff! Even Alan Moore, who wrote Watchmen as “the last superhero story” in 1987, spent some of his post-Watchmen career on more cheerful super-team stories, including WildC.A.T.s and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. He wanted a bit more optimism. Intrateam conflict makes stories exciting, but we also want to see extraordinary people come together and resolve their differences. At the end of the day, that’s a belief we need to put faith in—that peace between powers is possible.

Sunday: Variations on the theme, variations on the team! And tomorrow: what is the “double-double”?

I'm not sure I'd call The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen cheerful. The joy exists mainly in exploring the concept of a universe which includes every fictional character in existence. The setting itself & its inhabitants are grim and far from pleasant.