Siegel and Shuster’s first Superman was a bald villain, an altered human with mental powers. Their second Superman is more of a mystery. His story is lost to time—or, to be more precise, to a frustrated adolescent fit.

Elsewhere in this space, I discussed Detective Dan, the early full-length comic book. Two-fisted detective Dan Dunn, along with Ace King and Bob Scully, were characters launched by Consolidated Book Publishing, AKA Humor Publishing Co.

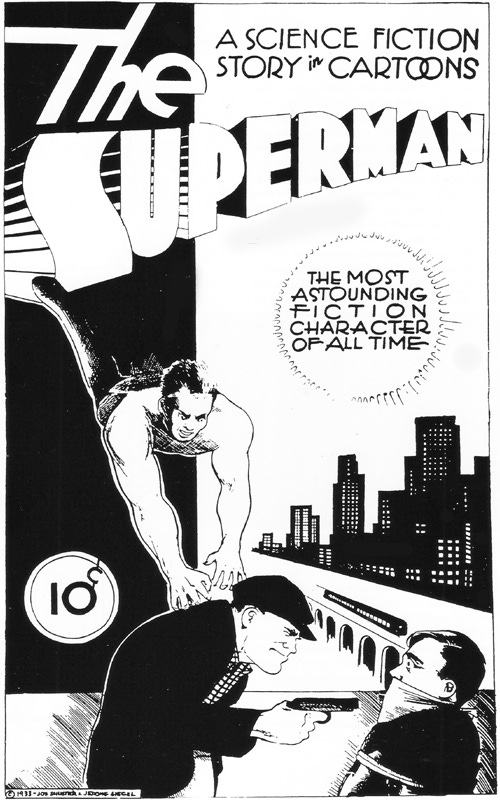

Siegel and Shuster loved what Consolidated was doing and sent it The Superman, a full-length comic of their own. Consolidated sent such a friendly note in reply that the boys believed they’d made a sale. But then the art came back. Consolidated got out of comic-book publishing after 1933: it’d do books until the 1950s.

Shuster took the rejection hard. Consolidated had been the only market for their work: no one else was putting out non-reprinted, periodical-length comics stories.

Siegel told two different stories about what happened next. The more plausible is that Shuster tore up the pages and threw them in the trash, keeping only the cover and a couple of partial sketches. The more colorful story is that Shuster made the pages into a bonfire on his backyard. Siegel, who lived only a few blocks away, smelled some kind of fire from his buddy’s house and came running, in time to save the cover but nothing else.

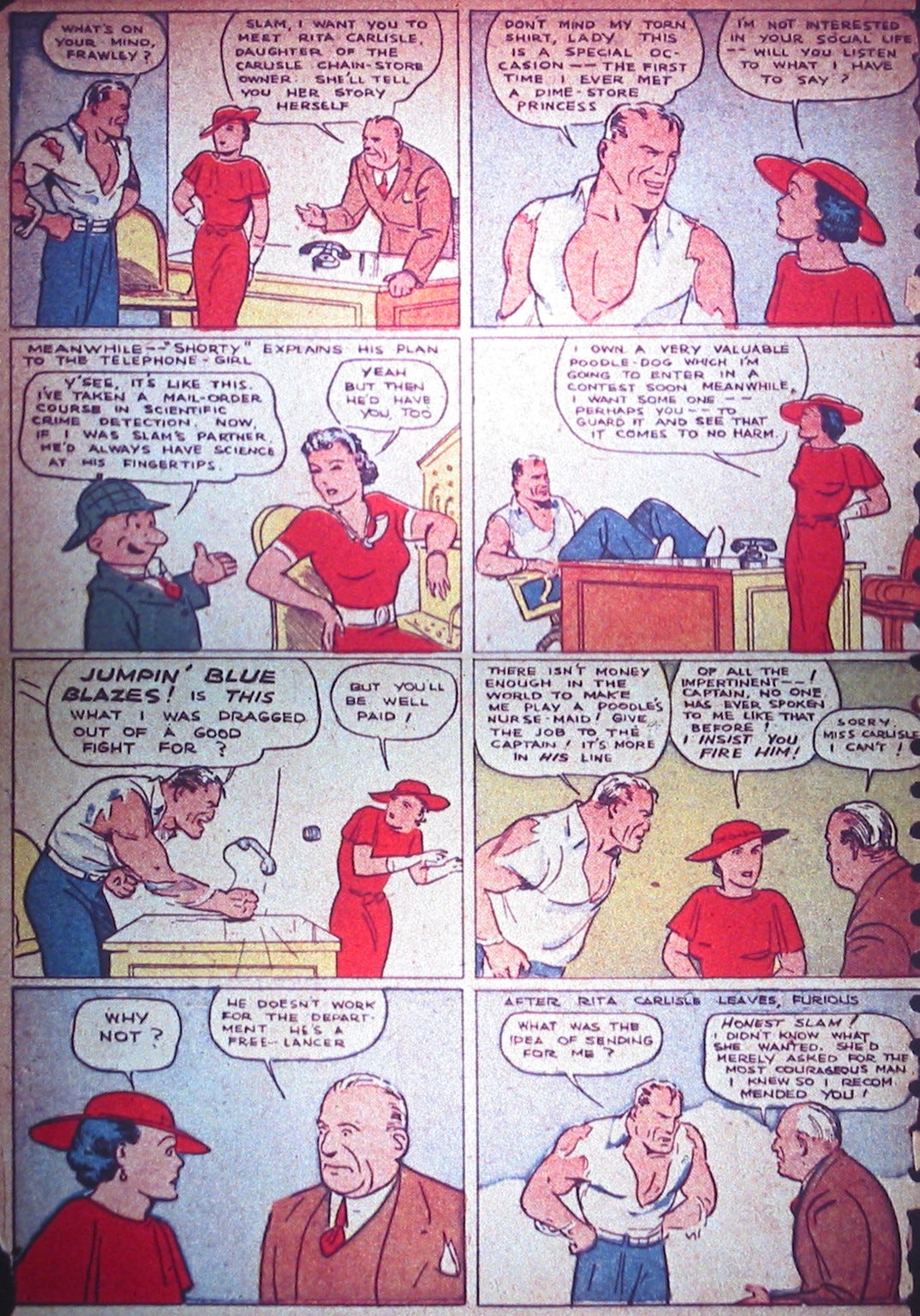

Siegel and Shuster’s memory of the second Superman seems unreliable in other ways. They both said the character resembled their 1937 creation, Slam Bradley, a sometime detective and wild fighter who got into stories that blended breathless action with comedy. Below is a selection from Slam’s first appearance, in Detective Comics #1:

“I can’t! He doesn’t work for the department!”

Some aspects of Slam’s stories share DNA with the final draft of Superman. The pampered nepo baby Rita Carlisle might not have earned her way in the world like the early Lois Lane, but she gives off a similar vibe. And Slam is willing and able to outfight anyone, anywhere, anyhow. (Later iterations of the character aged him past his brawler days, but that was after Siegel and Shuster had moved on.)

But there are reasons to doubt Slam resembled the second-draft Superman too closely. For one, he was made-to-order. The editor and publisher, Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, laid him out in a 1936 letter to Siegel:

We need some more work from you. We are getting out at least one new magazine in July and possibly two. The first one is definitely in the works. It will contain longer stories and fewer. From you and Shuster we need sixteen pages monthly. We want a detective hero called “Slam Bradley.” He is to be an amateur, called in by the police to help unravel difficult cases. He should combine both brains and brawn, be able to think quickly and reason cleverly and able as well to slam bang his way out of a bar room brawl or mob attack. Take every opportunity to show him in a torn shirt with swelling biceps and powerful torso à la Flash Gordon.

Wheeler-Nicholson’s note says nothing about the comical subversions Siegel and Shuster seasoned into the mix. And such comedy doesn’t seem likely to have figured into the Superman Mark II, either.

Take a careful look at that original 1933 cover. “The Superman” isn’t wearing even a torn shirt. Instead, he’s bare-chested and wearing what appear to be circus trunks—it’s ambiguous, but I think we can assume he’s not meant to be naked.

Slam is a prime specimen of 1930s manliness, brought up on the Cleveland streets. “The Superman” seems to be something other, something transhuman or at least on the outer edge of humanity. He may resemble another hero who would have been very much on Siegel and Shuster’s minds in 1933—the then-new Doc Savage, from the pulp magazine of the same name.

Savage—Clark Savage—owed his abilities to a team of scientists and educators conditioning him from birth. The first issue of his magazine came out in early ’33: issue #3 described him as a “superman.” He was later called “The Man of Bronze.”

After 1933, Siegel and Shuster’s designs got close to what hit the shelves in 1938, after they earned their publisher’s trust with Slam Bradley and other features. They got to realize their dream project. And it developed in ways they could never have expected—which would bring them both joy and sorrow.

But that’s another story.

Next: Micross time!