My favorite history teacher described 1848 as “the point at which history failed to turn.” Several 1848 events seemed like they could have changed history, but the stars didn’t quite align and old power structures resurged instead.

Superhero history has a few such points. I’ve mentioned “The K-Metal From Krypton”; that’s one. Here’s another.

From 1987-1992, the Justice League International adopted a tonal approach that could’ve reshaped the genre. It had a top-selling series (retitled twice: first Justice League, then with International, then with America), plus multiple spinoffs, annuals, and company-wide crossovers. Yet today, some younger fans have trouble believing it was ever successful.

My friends call the JLI “the funny League.” That’s more right than wrong, but not quite right. “The tonally varied League” would be closer to the truth.

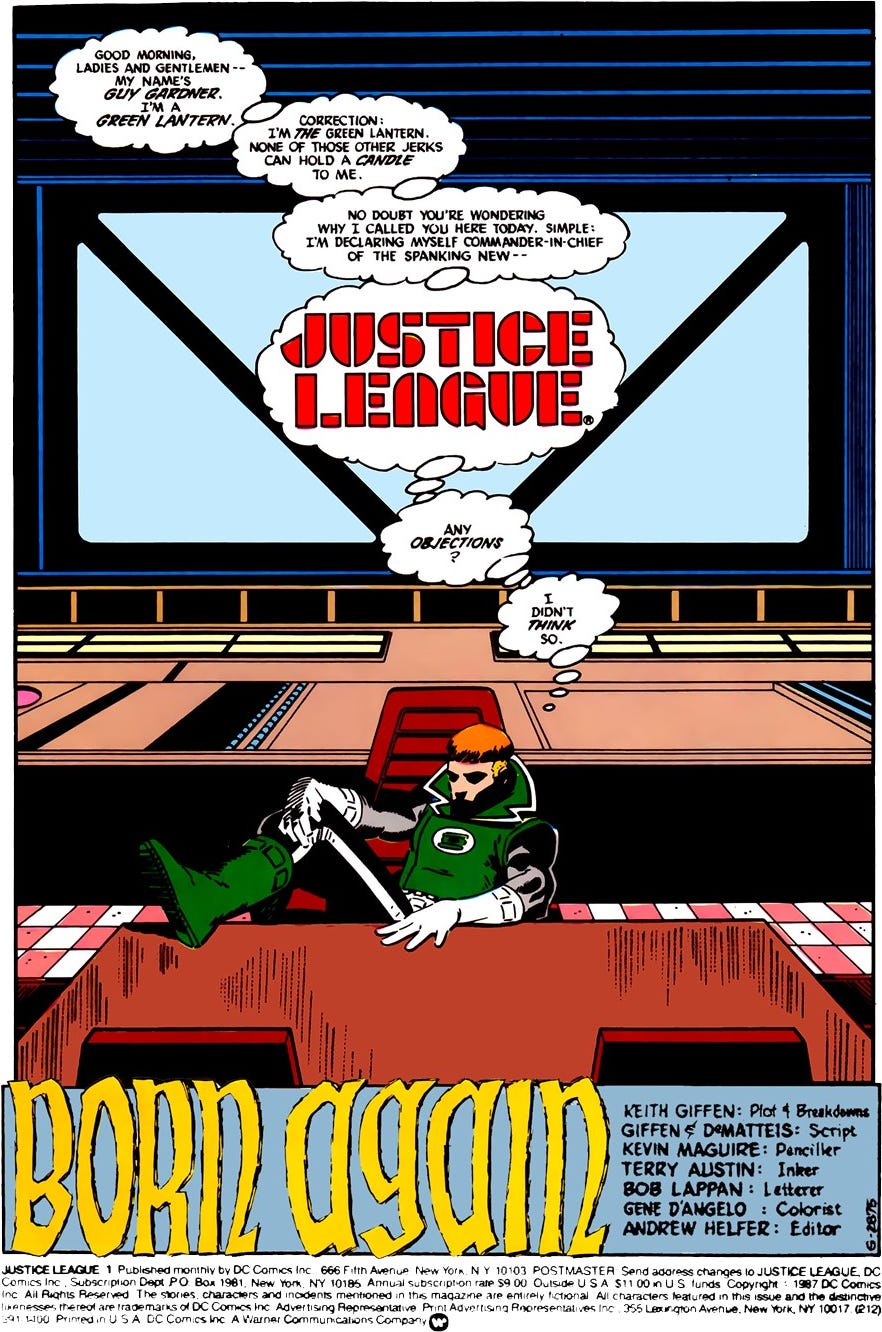

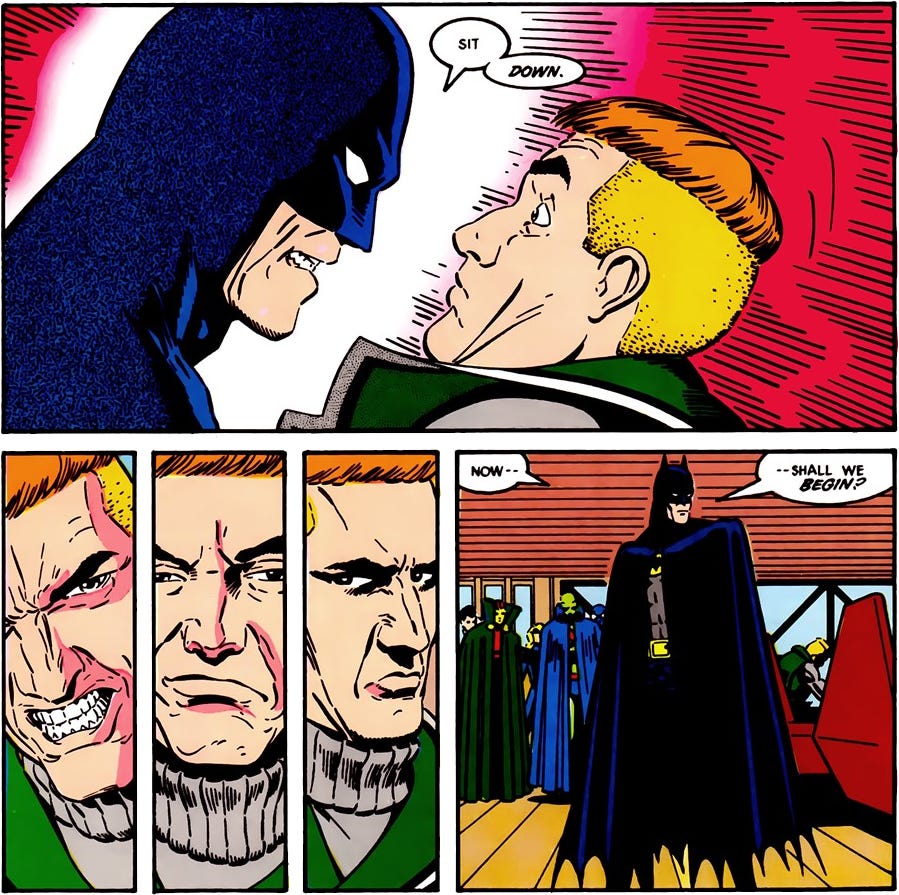

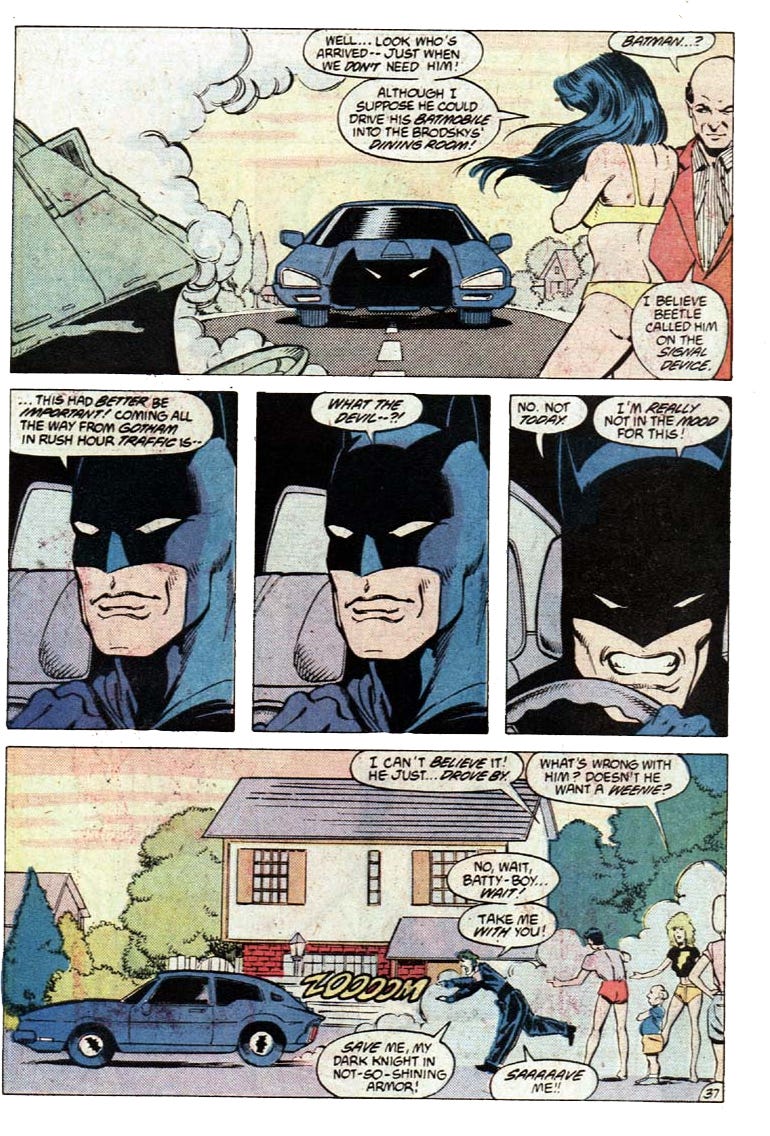

Its first issue featured a gripping battle at the UN building and a suspenseful mystery, both played straight. But these tend to be the scenes its readers remember:

And…

Genre-mixing is superhero tradition. The Fantastic Four mashed up superheroes with four other, then-popular genres—science fiction, romance, teen comics, monster comics.

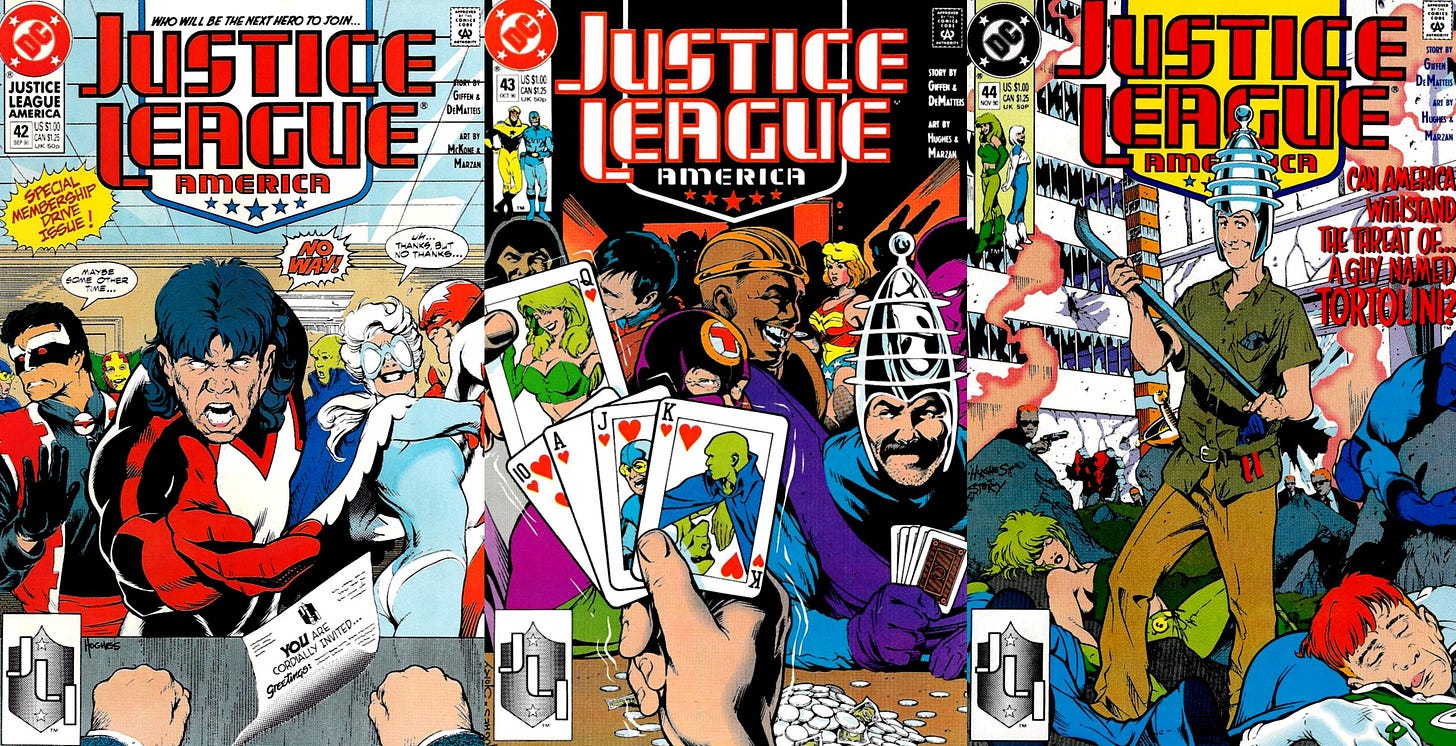

But nobody mixed comedy and action-adventure like the JLI. Five of its first 35 issues (#8, #24, #28, #33, #34) were more comedy than action-adventure. In one eleven-month period—#41-#51—that ratio shifted: more than half those stories skewed toward comedy.

And yet the prior year’s stories (#30, #37-40) contain startling darkness and brutality, culminating in grieving Leaguers turning on each other at a funeral.

Some of the JLI’s humor and drama came from the same place: a collective inferiority complex. The superhero A-listers—your Supermans, your Wonder Womans—weren’t available for this League. Even Batman was a part-timer. (This suited the creators fine—it gave them a longer leash.)

The rank and file knew they couldn’t live up to the status expected of THE JUSTICE LEAGUE, which led them to crack jokes—except Guy Gardner, who’d insist he was the greatest hero ever. No, you’re the arrogant ones for not realizing it, ya wimps! Make him the leader already!

This “non-elite” Justice League felt working-class. Mister Miracle and Big Barda, having escaped the hellish planet of Apokalips, valued nothing more than their quiet, suburban married life. Blue Beetle and Booster Gold were money-hungry enough to risk their Leaguer status on more than one get-rich-quick scheme. (“Beetlecoin, Booster! We’ll be trillionaires!” JLI Annual #2.)

This set them apart from heroes with vast fortunes (like Batman) or without any real need of money. (Superman doesn’t seem exactly dependent on his reporter’s salary. Spider-Man would fit right in, though.)

Plenty of offbeat, comical super-teams exist, some from DC or Marvel, some not.

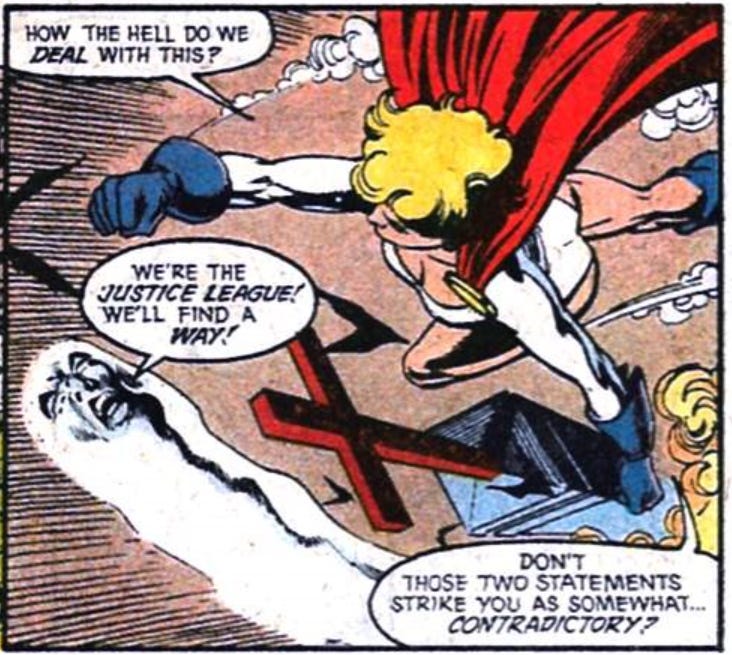

What’s never been done before or since was to make a major publisher’s central super-team such quirky misfits that questioning their competence became a running gag (JLA #32).

The exchange above, one of several like it from the JLI’s heyday, plays on two distinct meanings of Justice League, knowing readers would understand both. Justice League normally means an assemblage of the greatest superhero legends ever to wear tights—but here it also means, y’know, these guys. Yet, for a few years, this underdog Justice League outsold Superman and Batman.

Such success usually breeds imitation. Not this time. Superhero teams have done funny stories since, but not “JLI funny.” The Avengers never based a comedy routine on whether “Avengers” deserved respect or not. The Teen Titans never became an international franchise. The X-Men, though oppressed, never felt working-class.

Why not? Other trends were catching up with superhero comics then, including an “edgy” period, a speculator-fueled boom and bust, and more focus on serving the fanbase. JLI-style humor was too self-deprecating to thrive in any of that. By the time those trends faded, there were other successes to imitate.

There was also the auteur problem: no one could do “JLI” like the creators of the JLI. Its driving forces were Keith Giffen (who did plots and pencil-art breakdowns), and J.M. DeMatteis (who wrote dialogue) and artists gifted at comical expressions like Kevin Maguire and Adam Hughes. After five years on the series and its spinoffs, Giffen and DeMatteis left in 1992; Maguire and Hughes were already gone.

Writer-artist Dan Jurgens replaced them, bringing in Superman. But Superman—and Jurgens—seemed pretty impatient with these jokesters’ shenanigans (#63).

Pointing!

The 1993 “Death of Superman” storyline didn’t just kill Superman, it pretty much killed the JLI as a “fun” property. By 1995, Justice League America was indistinguishable from its mediocre contemporaries. And by 1997, DC had gone back to its classic “A-list” approach.

In decades since, some JLI members have gone bad or met brutal deaths, as if they needed to pay for the sin of not taking superhero matters seriously. (How dare they.) But DC has also published sequels; it now seems more nostalgic for the property than embarrassed about it.

Still, nothing will bring back the moment when the world’s premier super-team got its weenie roast interrupted by the Joker, and Batman decided not to arrest him because he didn’t want the aggravation (JLI Annual #2).

Those were the days.

Next Sunday, the tropes that define modern super-teams. And tomorrow, a call for Journal submissions!

BWAH-HA-HA-HA-HA!

Years later and I'm still annoyed by the decision to make Max Lord a super-villain. As I'm fond of repeating, it was probably something else Superboy-Prime did when he was punching reality. (And how's that for a ridiculous line that actually makes sense in context?)