What Rhymes With Iliad?

"Silly-ud"?

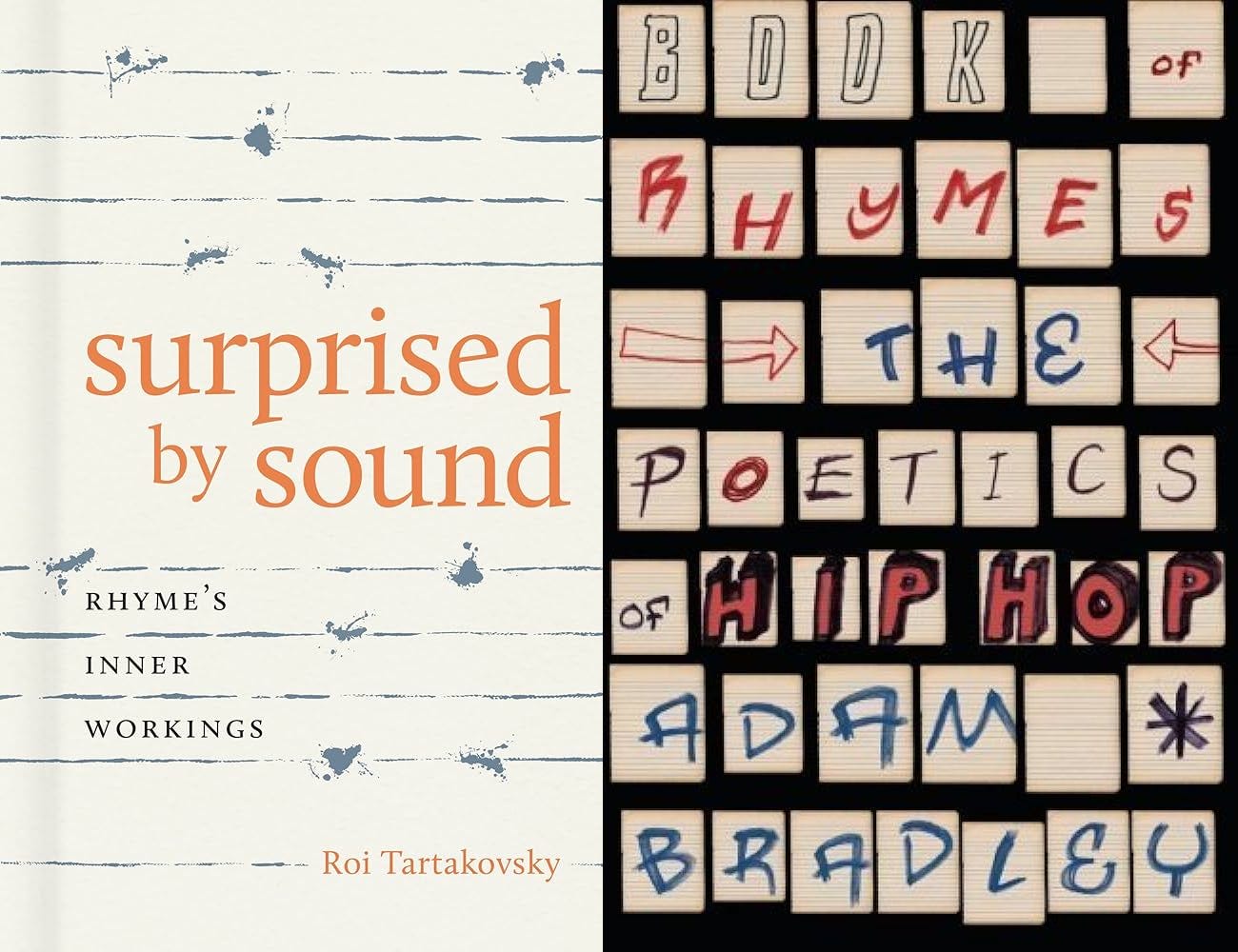

A couple days back, I said that roundups of wordplay often omitted rhyme when citing forms like anagrams, palindromes, and homophones. While that’s true for the general public, I didn’t mean to imply that wordplay studies have overlooked rhyme altogether. A quick look at Google Scholar confirms that’s not true, and there are other examples I could point to from Word Ways, syndicated language columnists, and books like The Book of Rhymes and Surprised by Sound.

One aspect of rhyme study that comes up a lot is rhyme in translation. When you translate a poem, should your translation rhyme?

Some poems rhymed in their original language and some did not. In many languages, rhyming is easier than it is in English—sometimes too easy, in which case the language-speakers add further rhyming constraints. In Arabic rhymed poems, not only do lines rhyme with each other, but the final word of each verse in the poem rhymes with that of every other verse.

The rhyme scheme of the Petrarchan sonnet is more restrictive than that of the Shakespearean, and that reflects their Italian and English origins. Although the last six lines of a Petrarchan sonnet vary, they always start with ABBAABBA—sometimes ABBAABBACDCDCD, sometimes ABBAABBACDECDE, sometimes ABBAABBACDDCDD or something else, but never getting past E. The ABBAABBA part has four A’s and four B’s, twin explosions of four-way rhyme.

Such rhyme is possible in English, of course, but it’s a bit more of a hurdle than in Italian. If you want to rhyme “silence” with “violence,” you’d better not do it at the start of a Petrarchan sonnet, or you’ll be stuck halfway through. You could try a slant rhyme like “pylons,” but that doesn’t feel like it’s in the classical spirit. Shakespearean sonnets are consistently ABABCDCDEFEFGG, making them a simple seven pairs of rhymes, much more manageable.

Other foreign-language poems couldn’t care less about rhyme. Haiku, by any of its several definitions and in English or in its native language, is not about rhyme but about beats. Even “syllables” is not quite the right term for Japanese haiku: its on are like syllables, but sometimes, they aren’t quite.

The Iliad was written in unrhymed dactylic hexameter. It broke out some alliteration now and then, but most of its prominent devices—simile, foreshadowing, personification—are not as related to the substance of its words and therefore are easier to translate.

To a modern audience, the question of whether to rhyme The Iliad may seem like a no-brainer. Translation is difficult enough as it is. Why add another constraint Homer didn’t have? Wouldn’t that make it even harder to convey the beauty, the connotations, the power of the original language?

But there is a case to be made for a rhyming Iliad. Rhymes “work” for a modern English reader the way unrhymed rhythm worked for the ancient Greeks. They confer a simple and powerful structure. That structure can help us through a sometimes challenging text. It keeps our brains engaged to know that, while we may struggle to keep track of how many people in this war are named Ajax and why they’re important, at least we know that the next line we read will rhyme with the line we’ve just read.

With tomorrow’s update, I’ll post a few samples from two different Iliad translations—one rhymed, one unrhymed—and you can see which one strikes your fancy better.