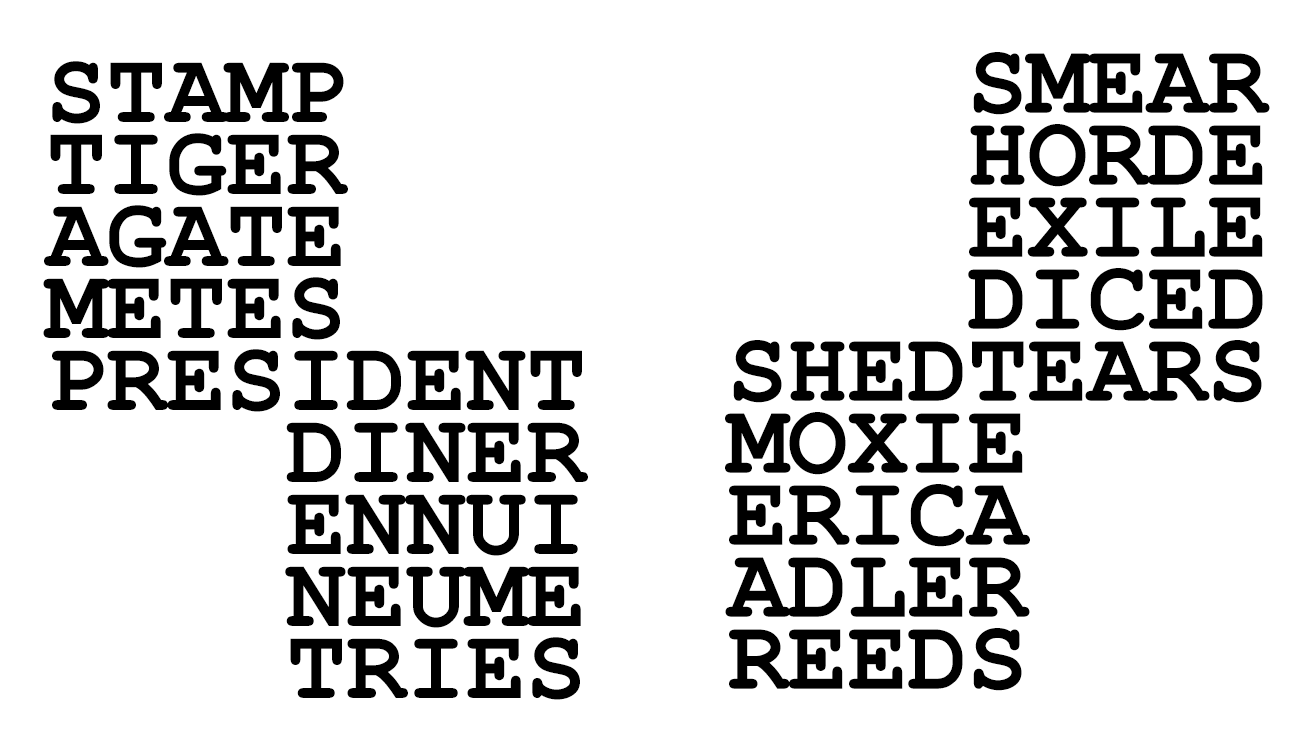

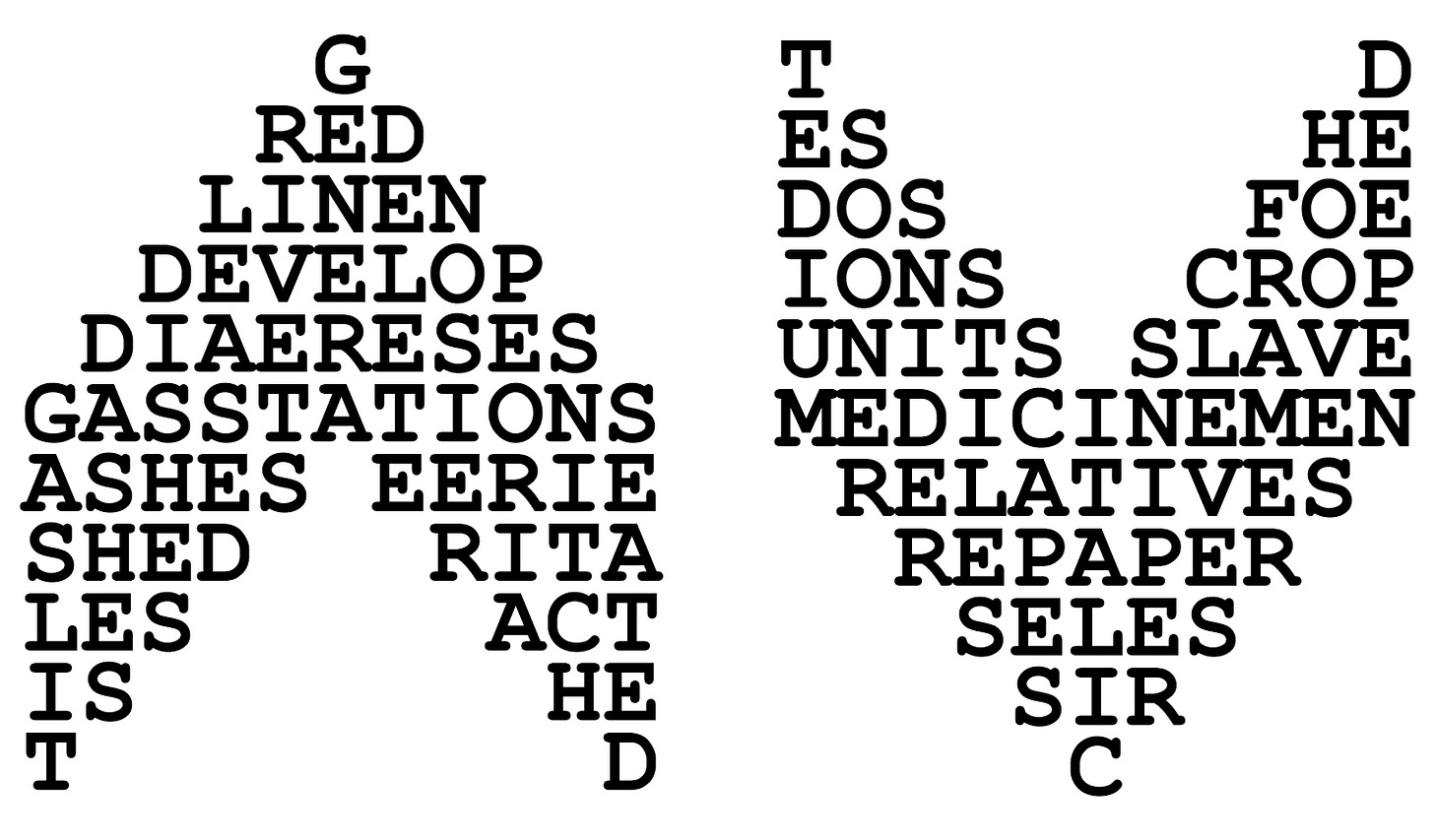

One of the forms we discussed last time was the windmill, resampled below:

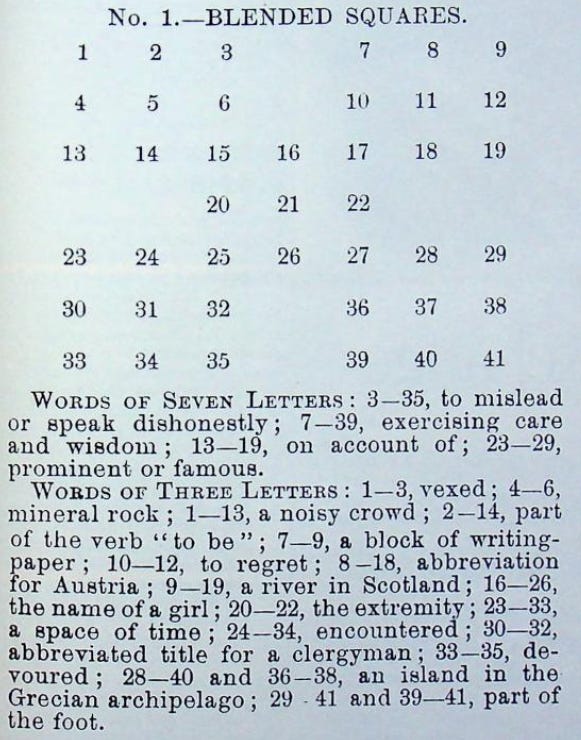

Windmills resemble two sets of overlapping word squares. In September 1904, The People’s Home Journal published a puzzle you could call an extended windmill, which it dubbed Blended Squares. The feature appeared ten times between 1904 and 1908. Here’s the first such puzzle, reproduced in GAMES Magazine #93, September 1988, by then-editor Will Shortz:

And here are the answers. Note that the bottom right corner of this construction contains two identical across and down answers, so this is a double form with a single corner.

Is it also a crossword? Back in 1988, Shortz posed that very same question:

A crossword is generally understood to be free of the constraints of simple geometric shapes, which means that crosswords are more complex constructions than forms, with more than one word in some rows and columns. Forms traditionally have only one word per line…

Is Blended Squares a crossword? That is the debate. The puzzle does meet the following generally accepted criteria: 1) Different words read across and down (except for the flawed lower right corner, which was fixed in later examples); 2) Some rows and columns have more than one word; and 3) A grid is presented for solvers, in this case a pattern of numbers showing the positions of the answer letters. The only feature that Blended Squares lacks is the now customary diagram of black and white squares.

Shortz polled ten experts on the matter, including then-New York Times crossword editor Eugene Maleska, constructor Arthur Schulman, and Penny Press editor-in-chief David Heller. The vote was six in favor of Blended Squares as a crossword, four against. Pretty close!

When I asked Shortz about this for my own book, he’d decided against it himself. Crosswords, in his view, need that diagram.

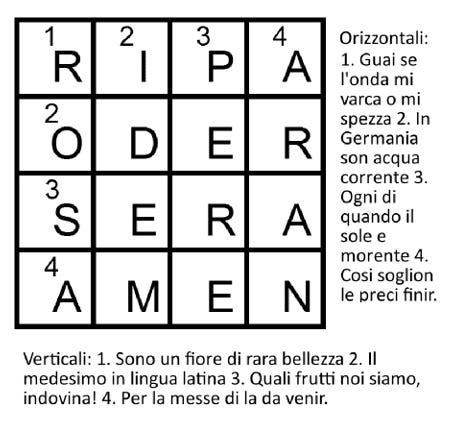

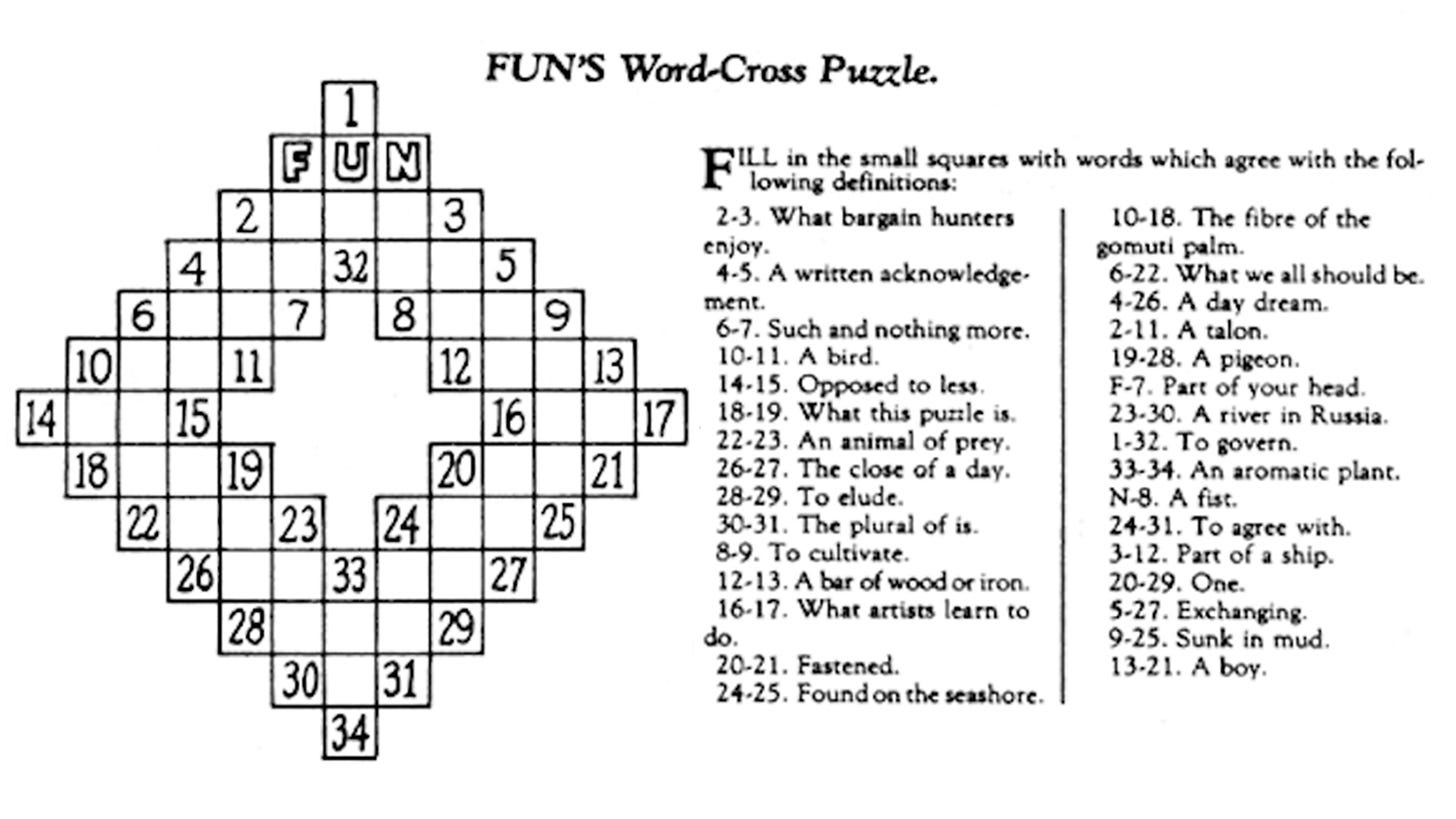

There were other “form” puzzles that had the diagram—but lacked some of the other criteria. The first was created by Giuseppe Airoldi in September 14, 1890, in issue 50 of Il Secolo Illustrato della Domenica, the bestselling newspaper in Italy. It meets criteria 1 and 3, too—but shapewise, it’s just a double word square:

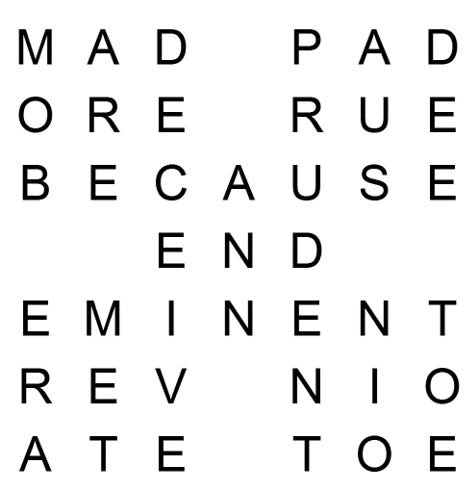

However, a couple of those “simple” forms Shortz mentions do allow for more than one word per line. There’s the chevron…

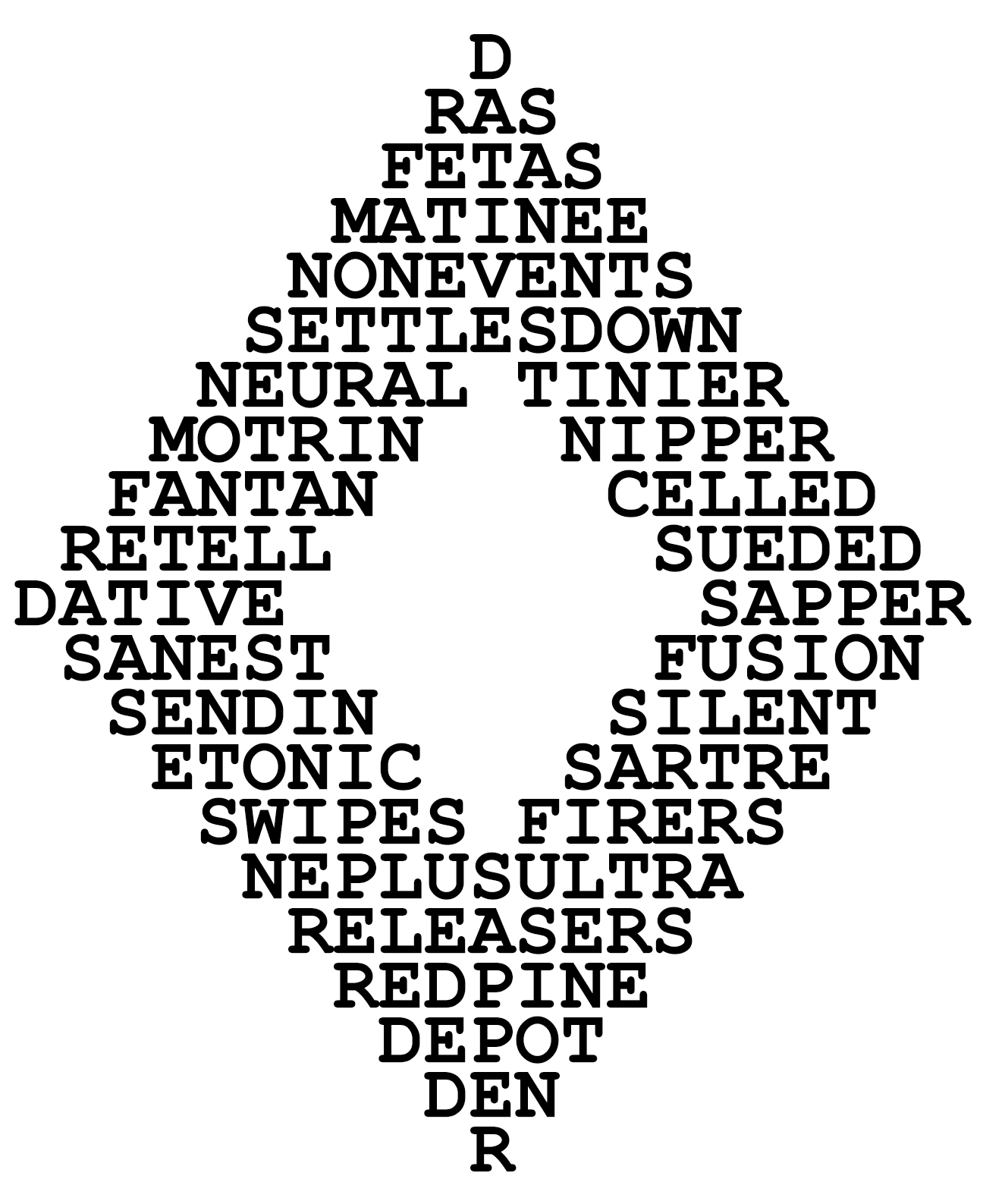

And the hollow diamond.

If you know Arthur Wynne’s first crossword, you might find the hollow diamond’s design familiar. Real, real familiar:

Of course, Wynne called this puzzle a “word-cross” then, which suggests another shape entirely. The National Puzzlers’ League didn’t have an example of this type for me to rip off sample, so I designed this one myself:

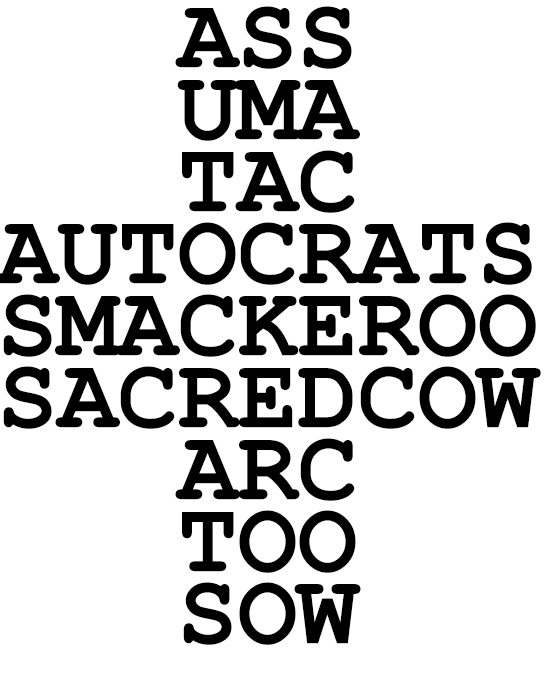

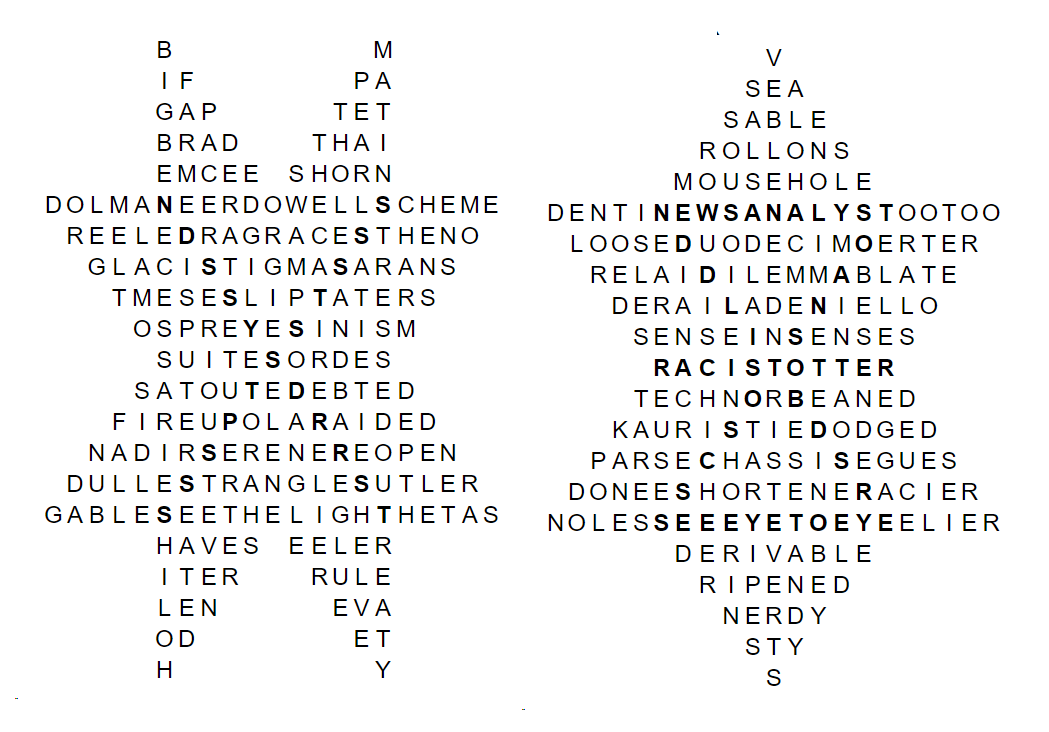

Just for completism’s sake, here are the most complicated forms the NPL lists, the chevron star and the Rokeby star. They’re basically smaller shapes welded together by matching edges. (The overlaps are in boldface in the images below, so the first long line of the chevron star is DOLMAN, NE’ER-DO-WELLS, and SCHEME while the first long line of the Rokeby is DENTIN, NEWS ANALYST, and TOO TOO. Also, the center of the Rokeby going across is RACIST and TOTTER, not RACIST OTTER.)

The first true crossword is thus very much a matter of opinion. I’d probably give the honor to the Sator square, distinguishing “crossword” from “crossword puzzle.” But the view in favor of Wynne is a valid one: sometimes an invention doesn’t really come together until all the elements are in place.

Next: A micross! And after that, a little more single-word play!