In prior installments, I’ve covered the many alternative answers to the question, “What was the first crossword?” But for most people, crossword history begins on December 21, 1913, with Arthur Wynne.

Some of the following research appears in my book On Crosswords; other facts are gathered from new sources I’ve hyperlinked. What follows is, I believe, the most complete account of Arthur Wynne’s life to date.

Wynne grew up in Liverpool, over seventy years before it would become known as the birthplace of the Beatles, and came to America at nineteen to become a journalist.

He wasn’t very good at it at first.

I was fired from every newspaper in Pittsburgh… just about walked in the door, took off my hat, picked it up and went out again. But even these short jobs gave me experience I needed... Finally, I got a job on the Pittsburgh Press, and stayed there for several years doing everything.

In time, Wynne graduated to the New York World, where he was responsible for fun—literally. The Fun supplement of comics, cartoons, riddles, jokes, and puzzles came out every Sunday. Among his duties, he improvised word puzzles for it: word squares, rebuses, hidden words, anagrams and connect-the-dots drawings.

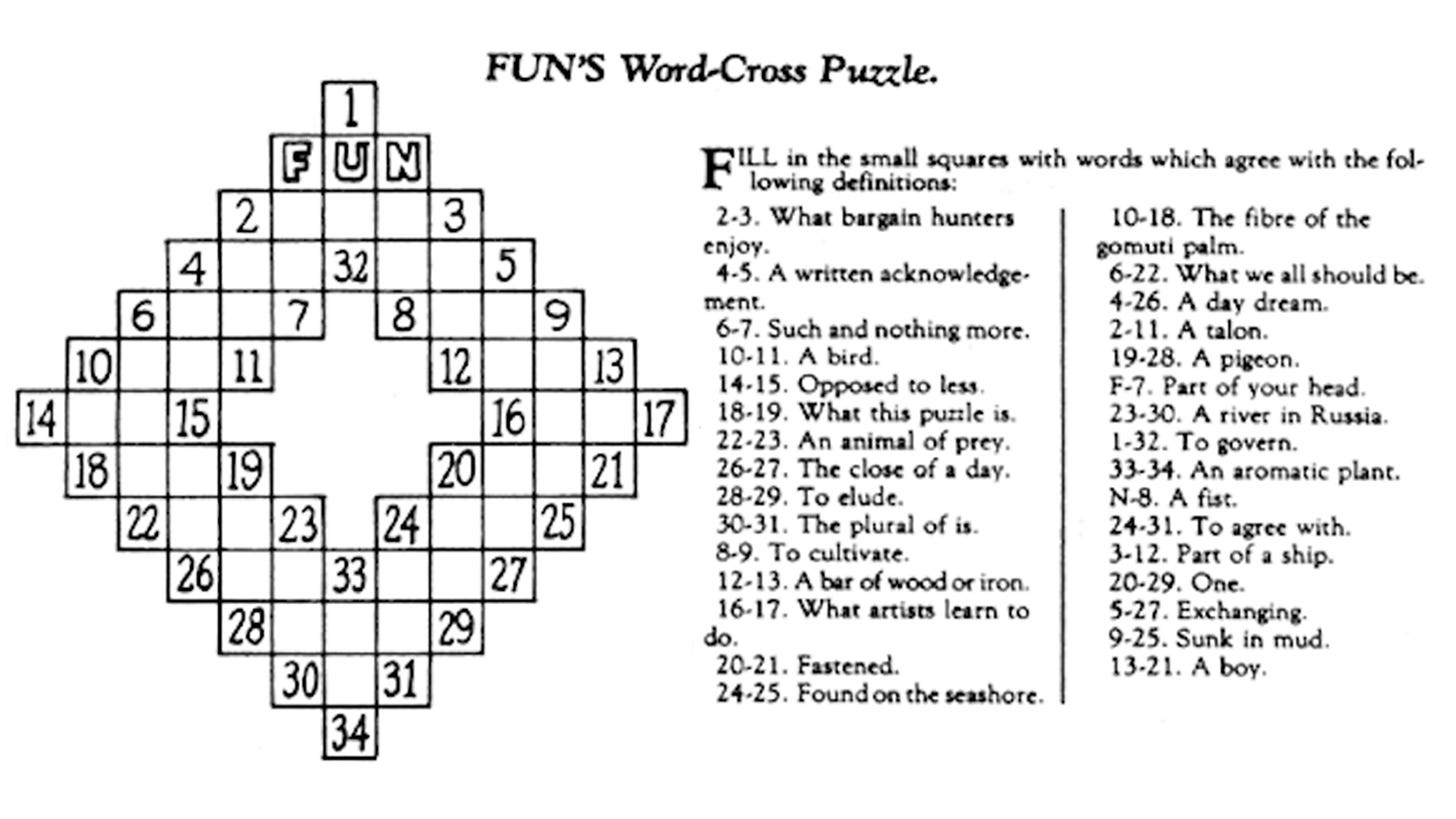

For the Christmas Fun, on December 21, 1913, he gave the readers something extra special: a hollow, double word diamond, presented in a grid for easier solving. Wynne would have been familiar with word forms, having solved them in Liverpool under his grandfather’s instruction.

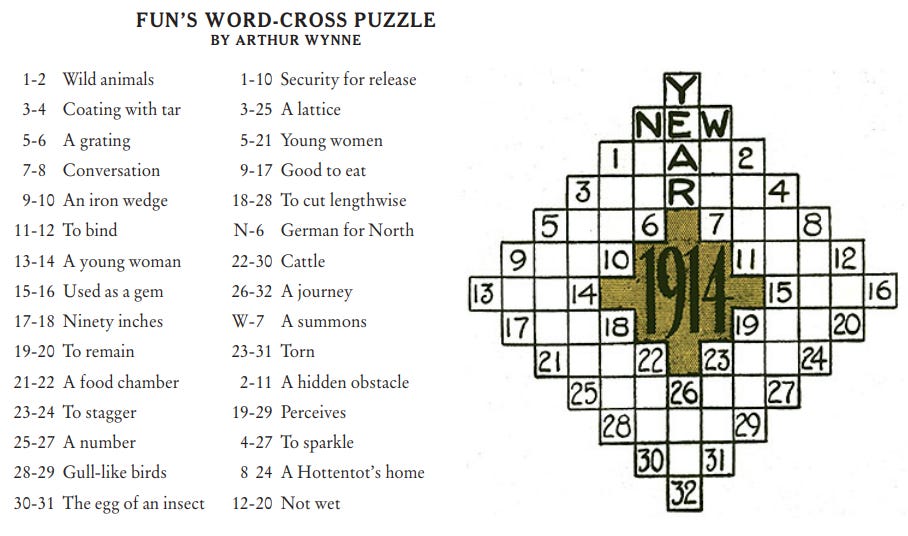

The “word-cross” still had a little evolution to do to become the modern crossword we know. This one had no black squares, and its huge indicator numbers denoted the endings of words as well as their beginnings. Still, response was immediate, and Wynne lost no time making it a weekly feature. The second installment was for New Year’s, published December 28.

Arthur Wynne himself was a true Renaissance man, but perhaps more comfortable as inventor than craftsperson. After inventing and renaming the basic puzzle, he invented its black squares…and then invented a system that saved him most of the work. Enthusiastic readers were sending in their own puzzles by the truckload: Wynne published samples of these until he moved on from the World and left his most famous creation behind.

After he left the World, he did most of his work for William Randolph Hearst-owned papers, including King Features Syndicate—for a time, he was editor in charge of its formidable Sunday comics section. He held numerous other editorial titles at different times: assistant managing editor of the Pittsburgh Press, managing editor of the Duquesne Herald, sports editor of the McKeesport Herald, and music editor of the Pittsburgh Dispatch.

In a weird coincidence, he was also social editor of the East Liverpool—but it was a paper in Liverpool, Ohio, not the British Liverpool in which he grew up.

Wynne wrote for the papers he edited, on topics ranging in importance from school plays to the latest inventions of Nikola Tesla. And Wynne shared some of Tesla’s spirit of restless innovation. An amateur architect, he designed an early version of the ejection seat, to be used in manned missiles to bring down that universally feared scourge of the air, the war Zeppelin.

One of the great frustrations of Wynne’s life was that the New York World wouldn’t help him patent the word-cross/crossword. Business manager F.D. White and assistant manager F.D. Carruthers nixed the idea:

[They said] such puzzles are hardly worth the trouble or expense; they said it was just one of those puzzle fads that people would get tired of within six months.

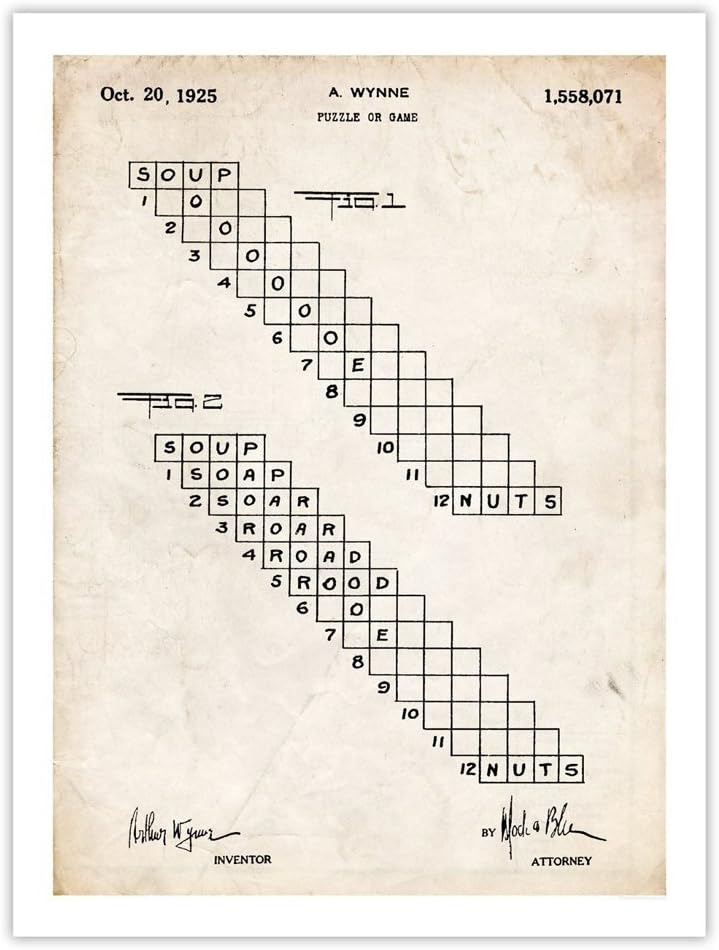

In 1925, Wynne and King Features Syndicate successfully patented the word ladder, a form of puzzle where one word is changed to another word, one letter at a time. You’ve probably done a word ladder yourself at some point.

Arthur met his first wife, Elizabeth Collins, in the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra—he was a second violin, she was a harpist. They married in 1895 and had one child, Rosa. Whether widowed or divorced, Arthur next married Lillian Webb in 1910, with whom he had two children, John and Janet. Janet lived until 2007.

The record suggests Lillian outlived Arthur, so their marriage had probably ended in divorce when he got married once more, to a much younger woman, and had one more child at 62, Kay. Kay was 12 when Arthur died at Indian Rocks Beach, near Clearwater, Florida, where he’d moved for health reasons four years earlier. The crossword great Merl Reagle interviewed Kay for the puzzle’s hundredth anniversary in 2013, when she was 80 and went by Kay W. Cutler: conflicting records suggest she passed away recently at 91.

Of course, this family history raises further questions—but since Wynne’s family was as private as he was, we’re unlikely to get those answers. Some spaces in the history book will always remain blank—or in Wynne’s case, perhaps, blacked in.

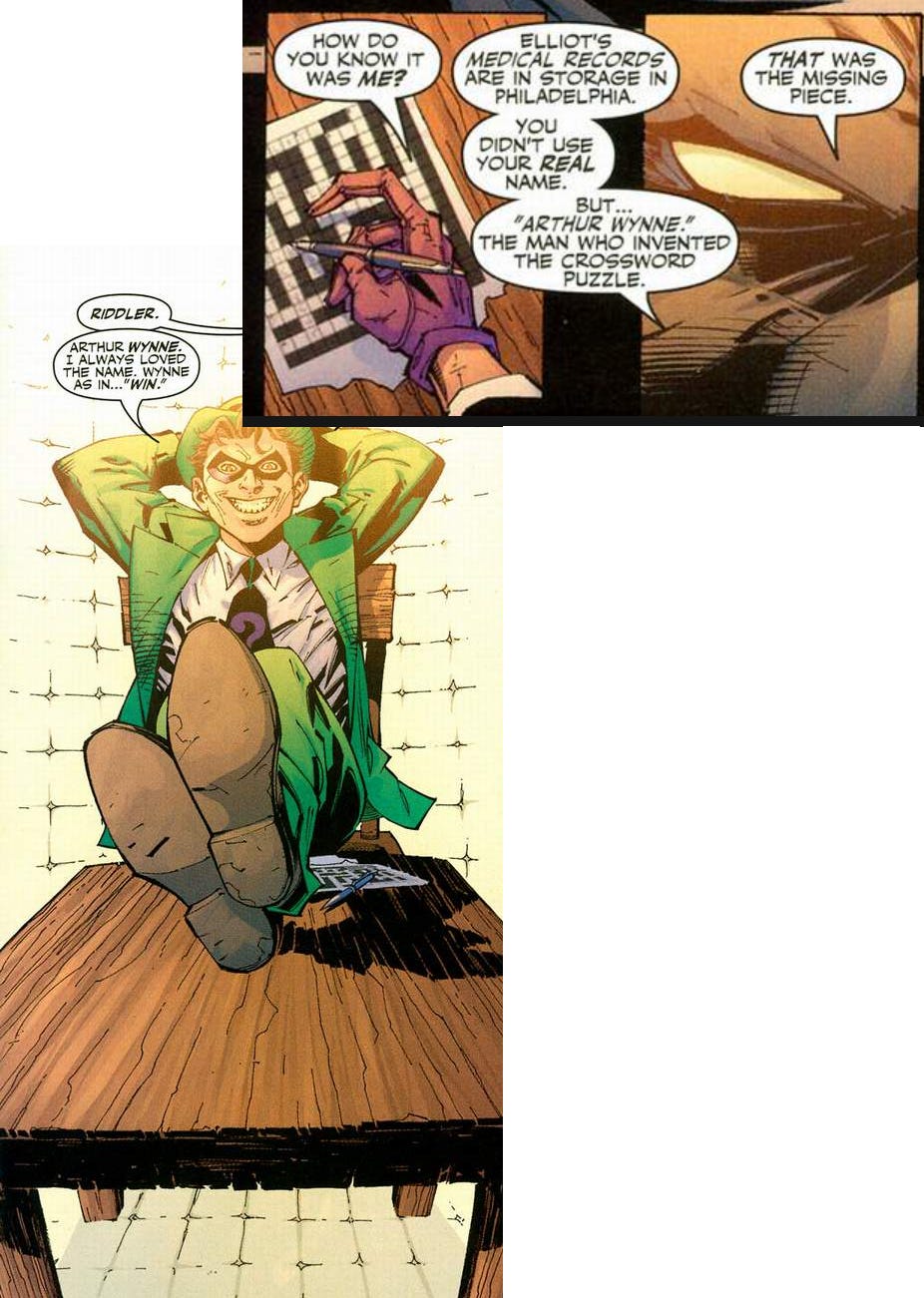

In the final analysis, Wynne has won a bit of fame and recognition among word lovers—just enough that he could become a puzzle answer himself. Or perhaps a mystery clue, as he did in Batman #619, 2003.

(No actual crossword designers were consulted in the making of the “puzzle” the Riddler is solving. #notacrossword. At least the creators had him do it in pen!)