Crossword Prehistory: Ancient to Post-Industrial

Or possibly the history of pre-crosswords.

Crosswords, most sources agree, had their beginnings on December 21, 1913. But I want to focus on the body of work that led up to that puzzle—it’s longer and more involved than most people think.

And there’s a lot of room for argument about definitions. But before we get into that, here’s a review (with links) of the earlier works I’ve covered in this space.

Crossword-style grids, as opposed to puzzles, go back as far as ancient Egypt, as documented here. Even using the Latin alphabet, such grids appeared in Pompeii, as I reported here—and one of them was the well-known Sator square.

The ancient-Egypt link above also shows early acrostic poems, which saw development in Babylonian literature (like the Babylonian Theodicy) and the Bible. An acrostic poem is like a very primitive crossword grid, one that has only one down entry.

The acrostic poem form continues to see use today—odds are good you can find one somewhere on the grounds of the average elementary school. But acrostic writings are a tiny minority compared to rhyming poems, and only a few of them are notable in English. I covered some of the modern instances of acrostics here.

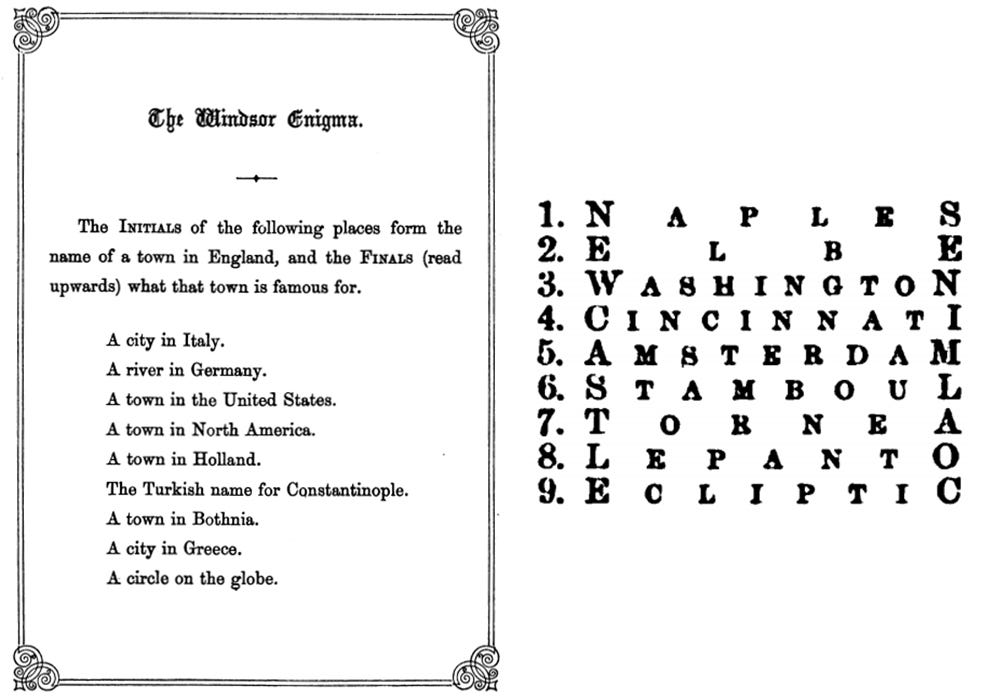

Still, they had a minor bloom in Victorian England. “A Boat Beneath a Sunny Sky,” in which Lewis Carroll acrosticized the name of Alice Pleasance Liddell, the same little girl who gave her name to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. A few other poems invoke the names of their secret dedicatees. And Queen Victoria herself got in on the act with the double-acrostic poem below, celebrating NEWCASTLE and its COAL MINES. Those mines led to the modern phrase “bringing coals to Newcastle,” indicating a redundant effort.

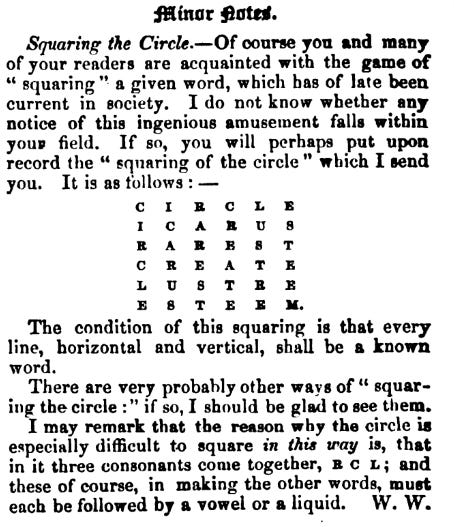

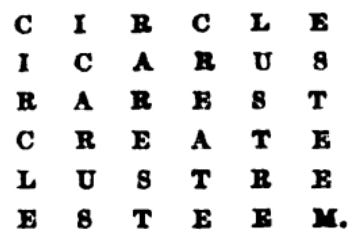

In the nineteenth century, English word squares grew common, though most tended to be small. The first that was six letters by six letters appeared on July 2, 1859, in the British magazine Notes & Queries, and is shown below in its original format, followed by a larger version for clarity.

The “Squaring the Circle” exercise is signed only “W.W.,” leaving its author a cypher.

Next to nothing is known about Frederick Planche, either. But Planche’s Guess Me, from 1872, contains the earliest examples I can find of a fill-it-in-yourself, cross-these-words puzzle. The answers are classic word squares, reading the same across and down, but you the reader are invited to fill them in:

The name of an insect my first;

My second no doubt you possess;

My third is my second transposed;

And my fourth is a shelter, I guess.

The answer is:

GNAT

NAME

AMEN

TENT

A few features of this early puzzle that would give a modern editor fits. The first and last clues are a bit vague, but crossword puzzles of fifty years later would still be using clues like “An insect” and “A shelter,” so we won’t demerit those. But “my second no doubt you possess” could be anything from “a body” to “a growing sense of impatience with this exercise,” and the third clue says only that it’s an anagram for the second. I do ironically enjoy the limp “I guess” at the end. (Should we put a rhyme into this quatrain, Frederick? “Oh, I guess.”)

Sorry to run late with this update: this one got away from me and called for extra research. Tomorrow, I’ll get further into the forms beyond squares and the unsurprisingly nerdy debate about just what a crossword is, anyway.