In this space, I’ve discussed some of the oldest acrostics—that’s “acrostic” in the single-crossing-message sense, not the giant-anagram-puzzle sense. More elaborate grids like the Paser stela and the Kheruef stela are rare in ancient writings, but acrostics? They pop up a little more often.

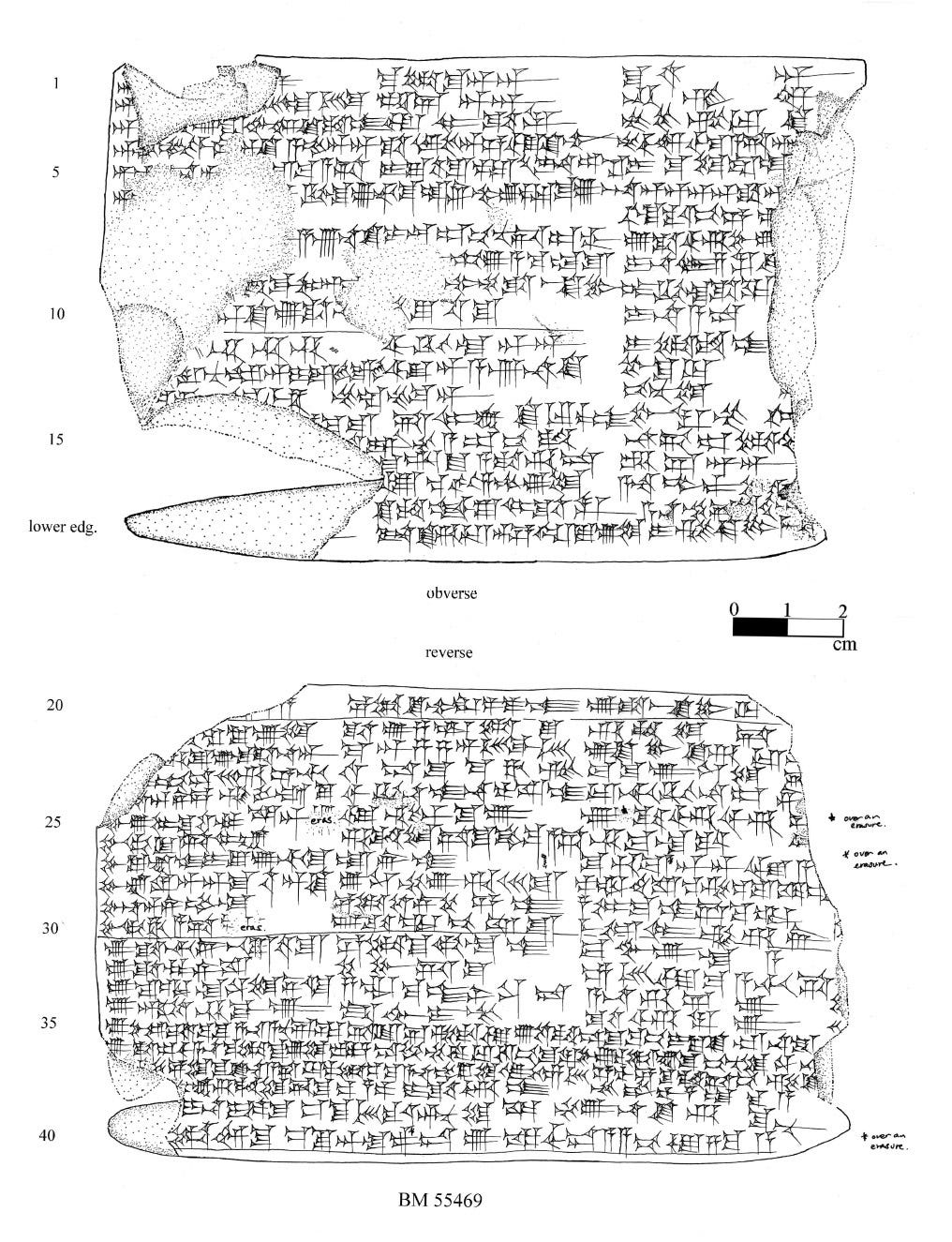

Seven such works come to us from the kingdom of Babylon: the Acrostic Hymn of Nebuchadnezzar II (pictured), the Hymn Concerning the Restoration of Babylon, the Prayer of Ashurbanipal to Marduk, a fragment of an acrostic prayer, a double-acrostic prayer to Nabû, another pair of double-acrostic prayers, and most famously, the Babylonian Theodicy. (Double-acrostics have two crossing messages, one at the front of each line and one at each line’s end.)

The Theodicy is the only one of these works that’s not simply praising gods or kings. It’s a tale of abandonment and misery that the author hopes to alleviate by sharing it. At 297 lines, it’s by far the longest example (though not all of those lines currently survive).

The signs of Babylonian language were syllabic, unlike our modern alphabet but like modern Japanese or early Mycenaean Greek. This leads to certain questions of translation.

As an example, Acrostic Hymn of Nebuchadnezzar II is four ten-line stanzas. Within each stanza, every line begins with the same sign; the resulting sequence of four lines translate as “Nabû the God!”

So if we were to try to repeat that effect into English, should those four signs come out as N-A-B-U? Or Na-bu-the-god? Maybe di-vine-Na-bu or Na-bu-di-vine? Ho-ly-Na-bu?

The question of should retreats before the question of could. A simple alphabetic acrostic gives you a lot of options, unless your predetermined starting letter is X, Q, or Z. But syllabic acrostics are far more challenging. I doubt I could reproduce one without stretching the rest of the original work out of recognition.

But I’ll try anyway. Here’s a few lines from the beginning and ending of the AHoN, based on the incomplete translation of Martina Schmidl:

Nabû, great lord god, advisor of the gods of heaven,

Number one of the great gods, the fathers, Enlil of the gods, lord of everything,

Noble god who loves justice and righteousness, who saves the earth…

[…]

Upheld in Nebuchadnezzar’s hand the just sceptre, the one that extends the land.

Under him placed the strong weapons that overcome his enemies.

Unto him bestowed the unsparing mace that defeats all foes.

Okay, but now let’s try it syllabically. The syllables god and vine (as in di-vine) don’t begin a lot of words, so Ho-ly-Na-bu seems like our best bet. We can cheat a bit by naming Nabû over and over in the first stanza, as the original author did:

Holy god Nabû, great lord, advisor of the gods of heaven,

holistic leader of the great gods, the fathers, Enlil of the gods, lord of everything,

holy god who loves justice and righteousness, who saves the ea[rth]…

But what about the other syllables? With these last three lines, I’m trying three different approaches, each of which could be applied to the other two. Nabû…

…Boon did make to Nebuchadnezzar of the just sceptre, the one that extends the land.

Boosted Nebuchadnezzar’s power with strong weapons that overcome his enemies.

Boom! Gave him the unsparing mace that defeats all foes.

These aren’t as bad as I thought they’d be when I got started, but they definitely take more liberties than the other kind.

This question of “acrostic-faithful translation” is something I might pursue further in The Journal of Wordplay or elsewhere. But tomorrow, I've got a little more fun with actor names…