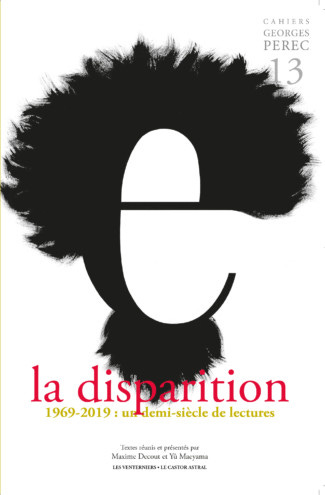

Georges Perec, the prolific, experimental French author of A Void and The Exeter Texts, also wrote Life: A User’s Manual, Things: A Story of the Sixties, A Man Asleep, Ellis Island, and W, or a Memory of Childhood, among others.

His work features self-imposed constraints channeling wild imaginative freedom—and though he failed to become a graphic artist, a graphic sensibility runs through it. Things and Life are organized around objects and apartments. He co-directed A Man Asleep as a film. And in his lipograms and W, the presence or absence of letters on the page is its own visual element, as if Perec were painting with his typewriter.

While he kept his stories moving, Perec loved lists and details, and he thrived on challenges that’d intimidate other writers. Life: A User’s Manual takes place over 99 rooms and within a single moment. W bridges memoir, science fiction, and historical fiction. Perec wrote another memoir, consisting of 480 stand-alone sentences all starting with “I remember.” His other works include a giant palindrome and a weekly crossword—both, sadly, untranslatable from French. He was always finding new organizing principles for prose, and took pride in never repeating himself.

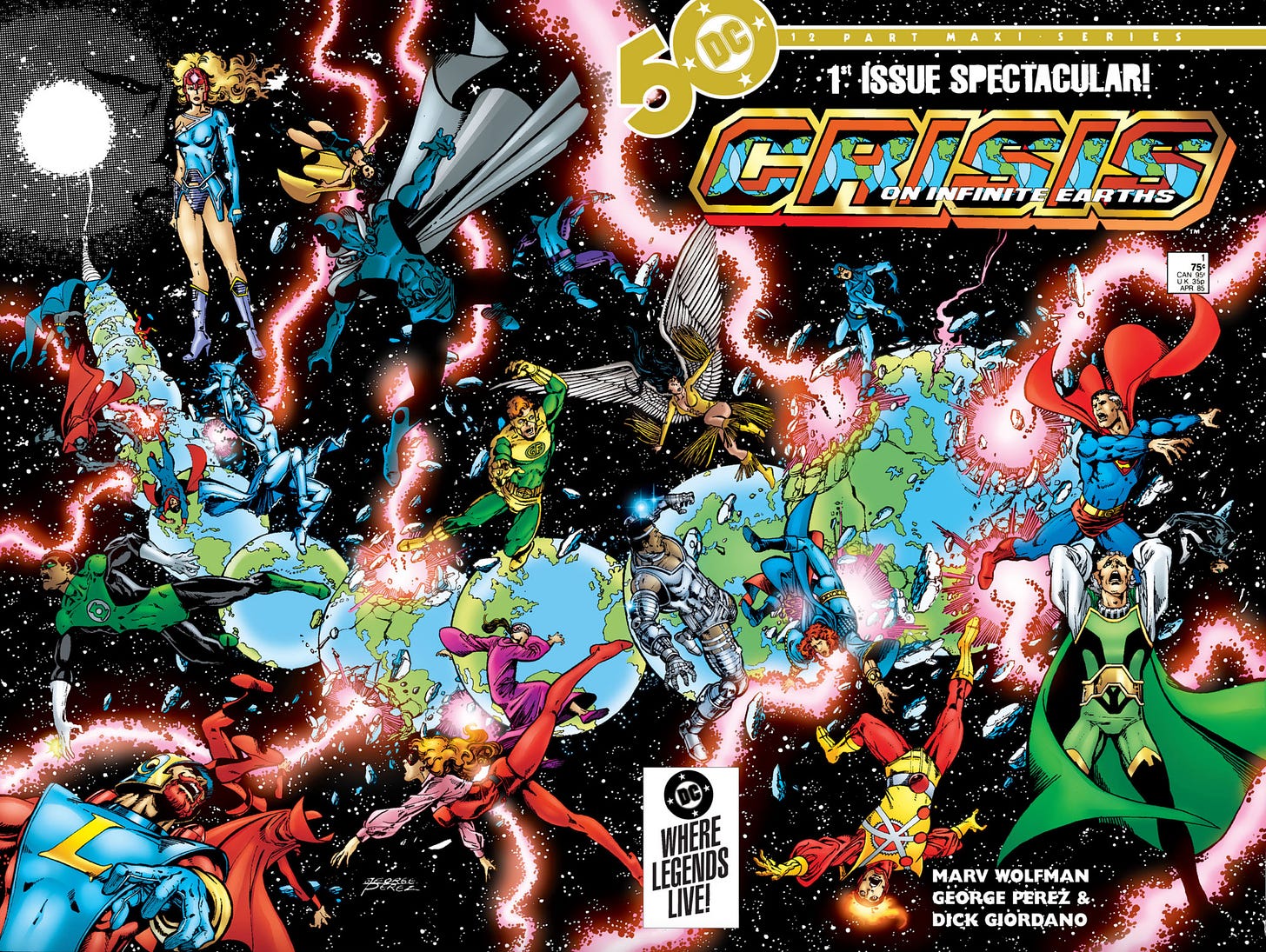

George Pérez (seen here with his wife and some favorite characters), the prolific, self-taught American comic-book artist of JLA/Avengers, also drew Teen Titans, Crisis on Infinite Earths, The Infinity Gauntlet, Wonder Woman, and Sirens, among others.

His work features self-imposed and commercial constraints channeling wild imaginative freedom—and though he often preferred working with scriptwriters to writing his own work, a storyteller’s sensibility runs through it. With both his “infinite” titles, he pioneered a sort of Homeric approach that coordinated hundreds of characters into one epic tale. Teen Titans broke taboos of its time and even defied its own title, allowing its key characters to come of age and leave old roles behind. One sees echoes of those accomplishments in the crowded tales of the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the many Teen Titans TV adaptations.

While he kept his stories moving, Pérez loved crowd scenes and details, and he thrived on challenges that’d intimidate other artists. While the comic-book page often contains four or five frames on average, Pérez pages were more likely to average seven. He was always finding new organizing principles for those pages, and while most of his work was firmly in the superhero genre, he had a way of making its well-worn tropes seem continually fresh and new, reinventing them with explosive action or even defying them altogether.

These two names are practically homophones, come from the same roots, and they’ve sometimes been Americanized to look even more alike. The s was left out of “George Perec” in some early translations. Comic-book letterers often left the accent out of “Perez,” and so did Pérez’s own style of signing his art for much of his life.

Both men were creative and playful yet unflinchingly disciplined, changing the definitions of what could be done in their fields. Both were very much of their nations and a little bit foreign to them. Perec’s writing sometimes wonders what it’d be like to be some other nationality, and he was haunted by the early loss of his parents. Pérez, the child of Puerto Rican immigrants, introduced Marvel’s first Puerto Rican hero early in his career. And he did some of his most personal work with a fresh-off-the-island version of Wonder Woman, uncharacteristically writing most of it himself.

Getting personal, though, was more Perec’s thing than Pérez’s. Perec rejected consumer culture and explored his canvas for its own sake. Pérez embraced his brand as a commercial artist, and even when self-publishing independent work, he tended to use ensemble casts who bore no resemblance to his own self-portraits.

Perec may have been easy to know through his work, and he had loyal friends, but he could be difficult in person. Pérez, by contrast, was about as beloved as a comics artist can get. I had the privilege of tabling with him at a few shows, and the warmth and generosity just flowed out of the man. I don’t think the lack of autobiography in his work is due to commercialism or self-censorship. I think he was just a person who was more interested in other people than in himself.

Perec died of cancer in 1982, at 45, far too young. Pérez died of cancer in 2022 at 67, far too young.

Both have been powerful influences on me—Pérez since childhood, Perec much more recently. What happens when you bring those influences together?

I guess we’ll find out.