The Simplest Crosswords (Untercrossen?)

Breaking it down to the basics.

A crossword designer often wonders, Is this word too obscure? Are these pairs of crossed words too obscure? While it’s nice for a solver to have their esoteric knowledge rewarded (like knowing what the word “esoteric” means), too much obscurity can make a puzzle useless to the general public.

What if puzzles were made only with the goal to maximize accessibility? What would that look like?

To help answer that question, I tested out making puzzles from a word list limited to the most common words in the English language. My source was the Corpus of Contemporary American English, the most extensive and recent major cross-study of English words as they’re used in America. The full list is expensive (especially for non-academics), but the commonest 5,000 words are available for free, and I judged those to be sufficient for my purposes here.

Words are here considered to be single, simple formations of letters, meaning that “is” is distinct from “be” and “elephant” from “elephants.” Some other lists of “common words” use lemmas, putting all conjugated forms of a word into the same family and listing by family, but that’s not what we’ll do here.

I didn’t have to dip too far into the list to find my first crossing. Using only the top two most-frequently-used words, this crossword design is the lexically simplest ever made:

This assumes, of course, that the commonest words are the easiest to clue and solve, but with so many fill-in-the-blank options for these words (over ___ counter, signal ___ noise), they seem straightforward enough.

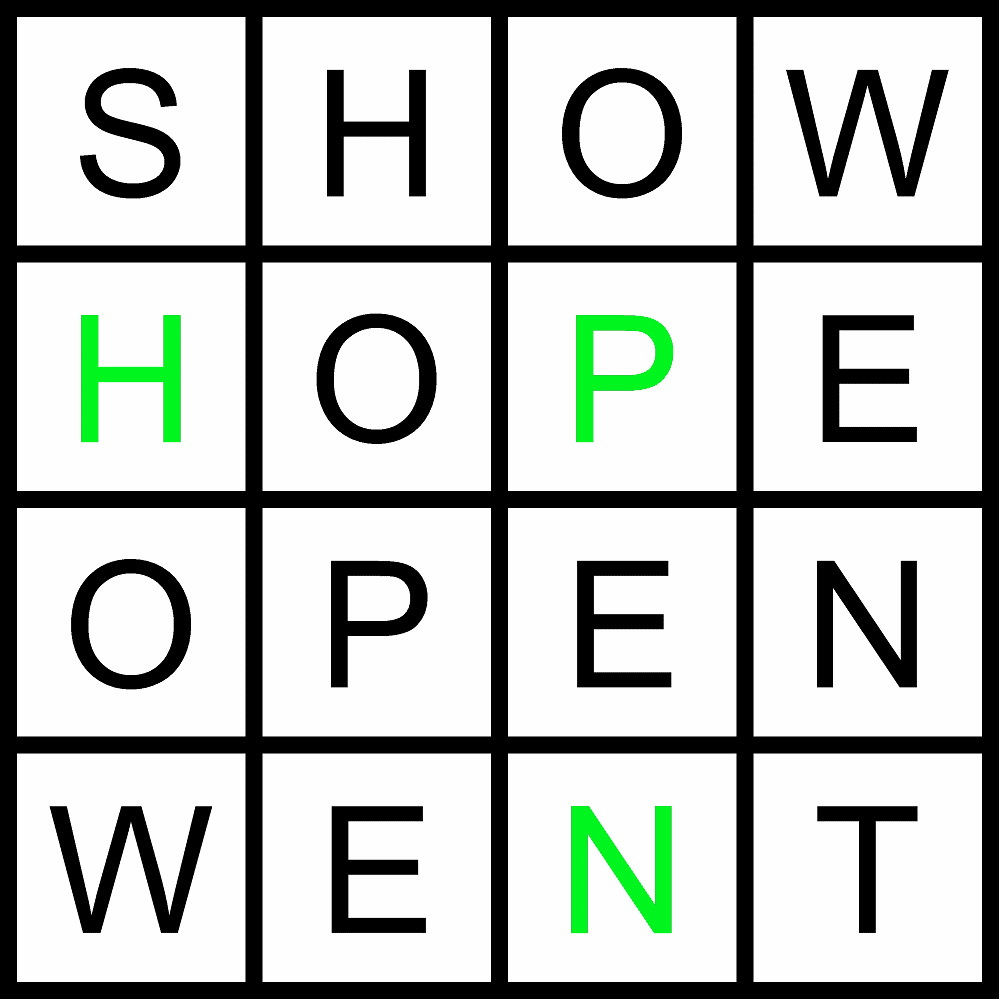

Of course, this is barely a crossword even by a relaxed definition. Some call puzzles “criss-crosses” when they don’t have sufficient crossings. An American-style crossword has the rule that every letter must be part of two different words. By that definition, we can get the simplest crossword by using the top 49 words (no is 49th):

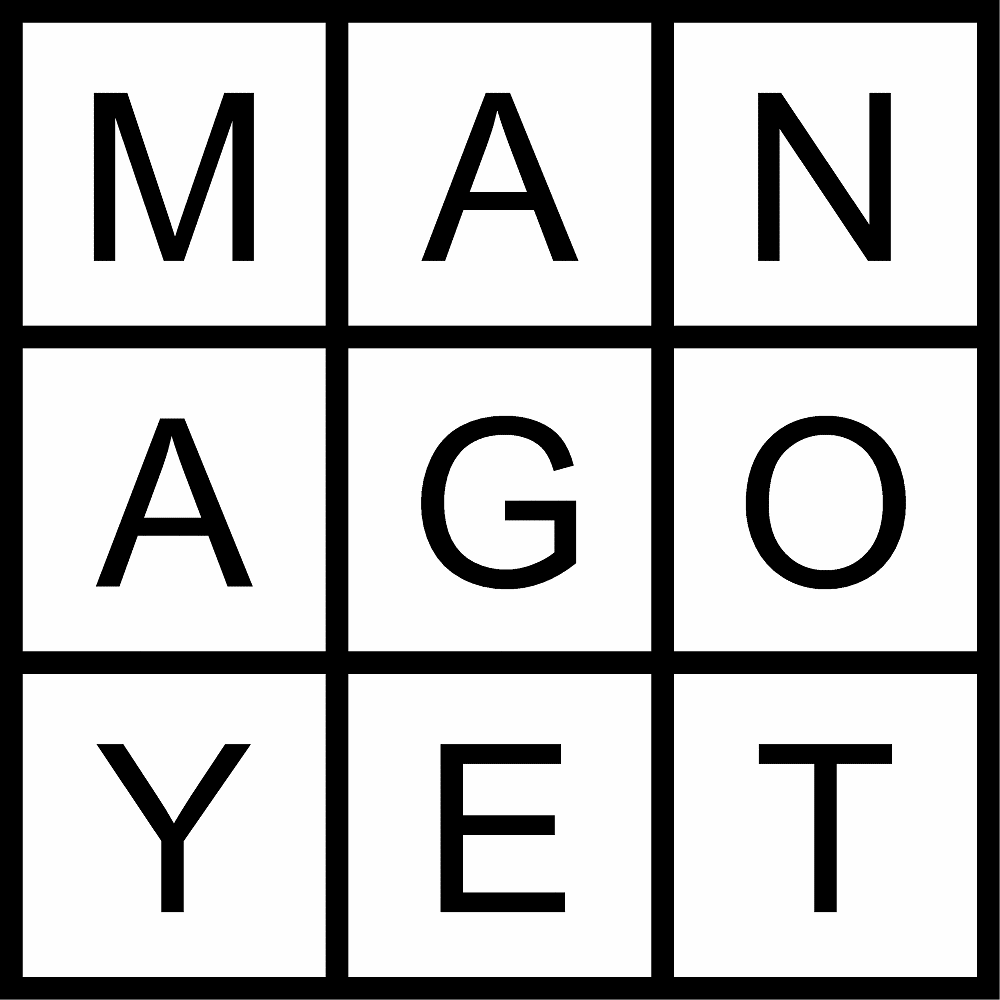

Crosswords in most markets also eschew two-letter words, so what’s the simplest crossword we can make that follows that rule, too? For this, we need the top 500 words, or at least the top 458. Age is the 458th-commonest word and the most uncommon word in the grid below. At 24th, not is the commonest. And even in this common-words-only space, unconventional vowel patterns like AGO’s ending “o” start to get useful.

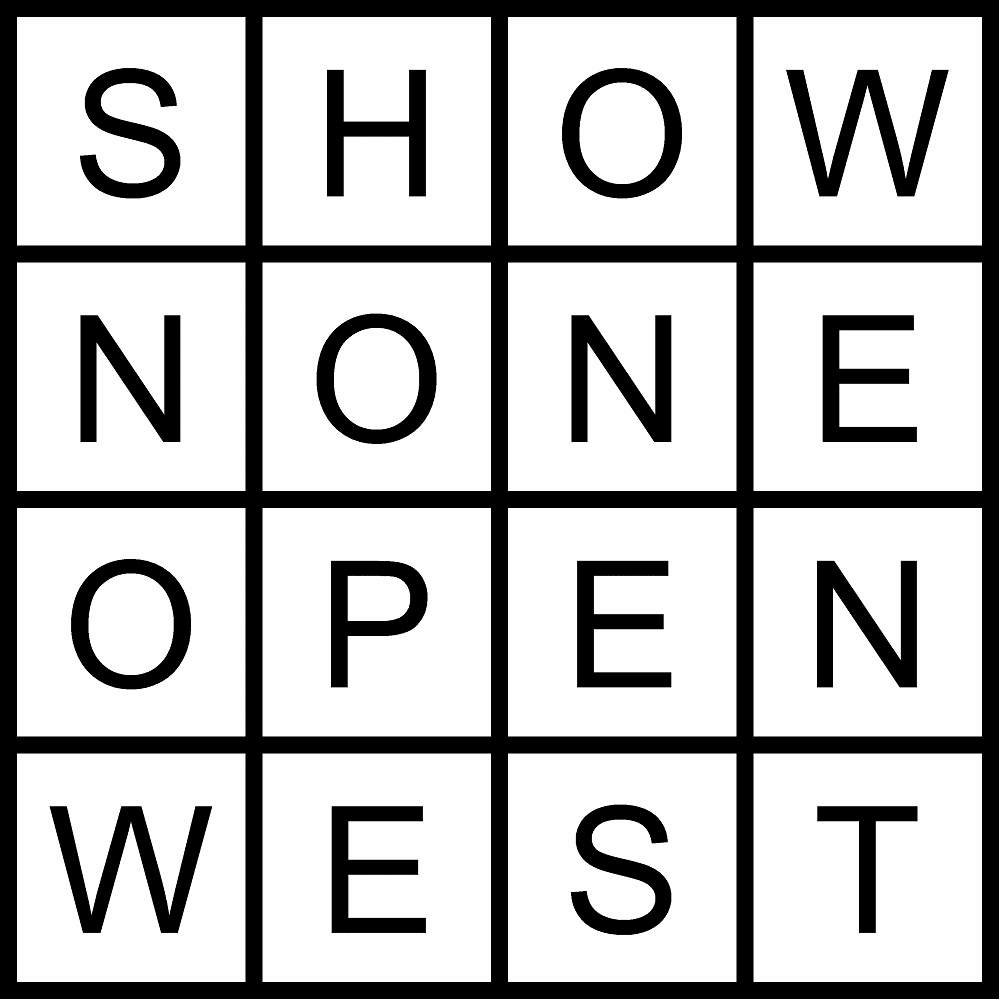

Here’s the commonest 4x4 grid (with no black squares) that I could find. It’s the only one that is limited to the top 2,000 words. Went at 232 and snow at 1838 are the frequency outliers on this one.

What I find interesting about this design is that it’s almost as close as it can get to being a word square, an ancestor of the crossword form that differs chiefly by not using any black squares and reading the same across and down. By changing only three letters out of sixteen, you can transform the grid into word-square format:

(It is possible to make a crossword slightly closer to this word square: the original grid could have used NOPE and OPES instead of NONE and ONES. But obviously, those words are not common enough to be part of this exercise.)

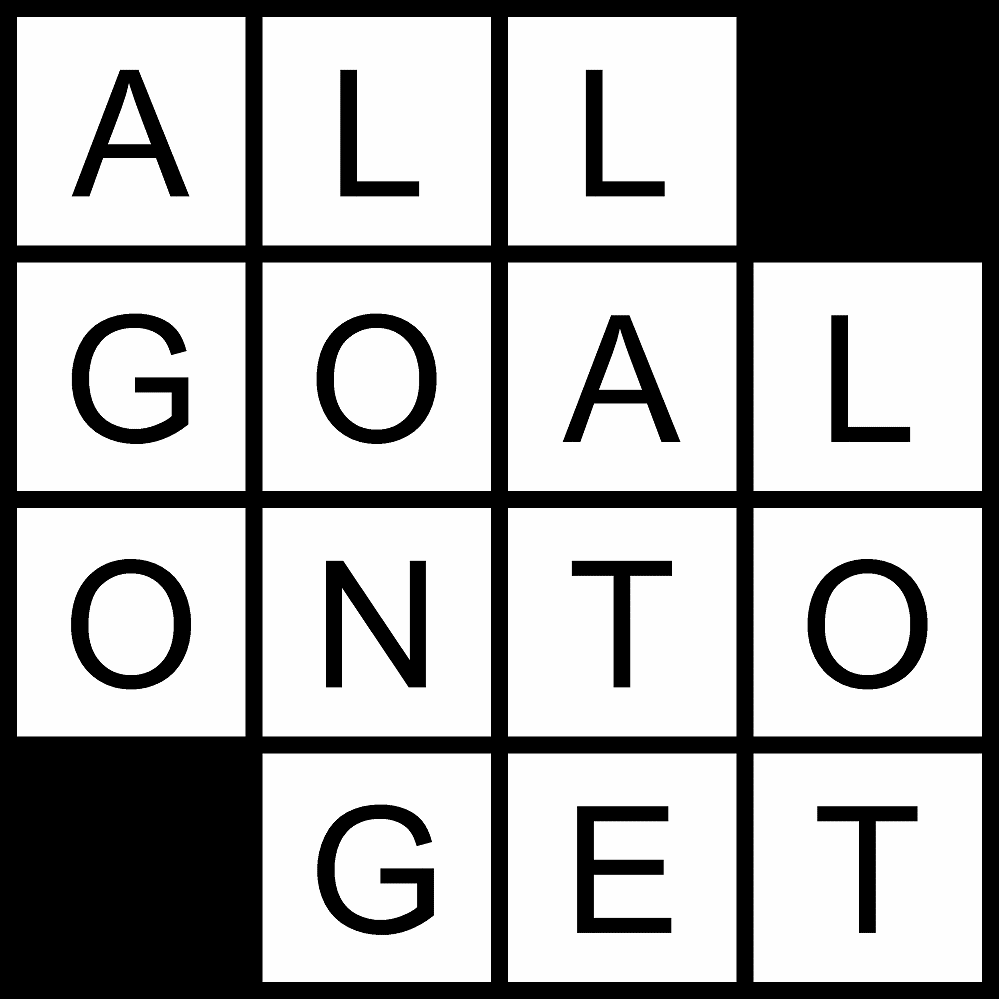

Naturally, what can be done with a fully white grid can also be done with a black square or two. Here’s another one using the top 2,000:

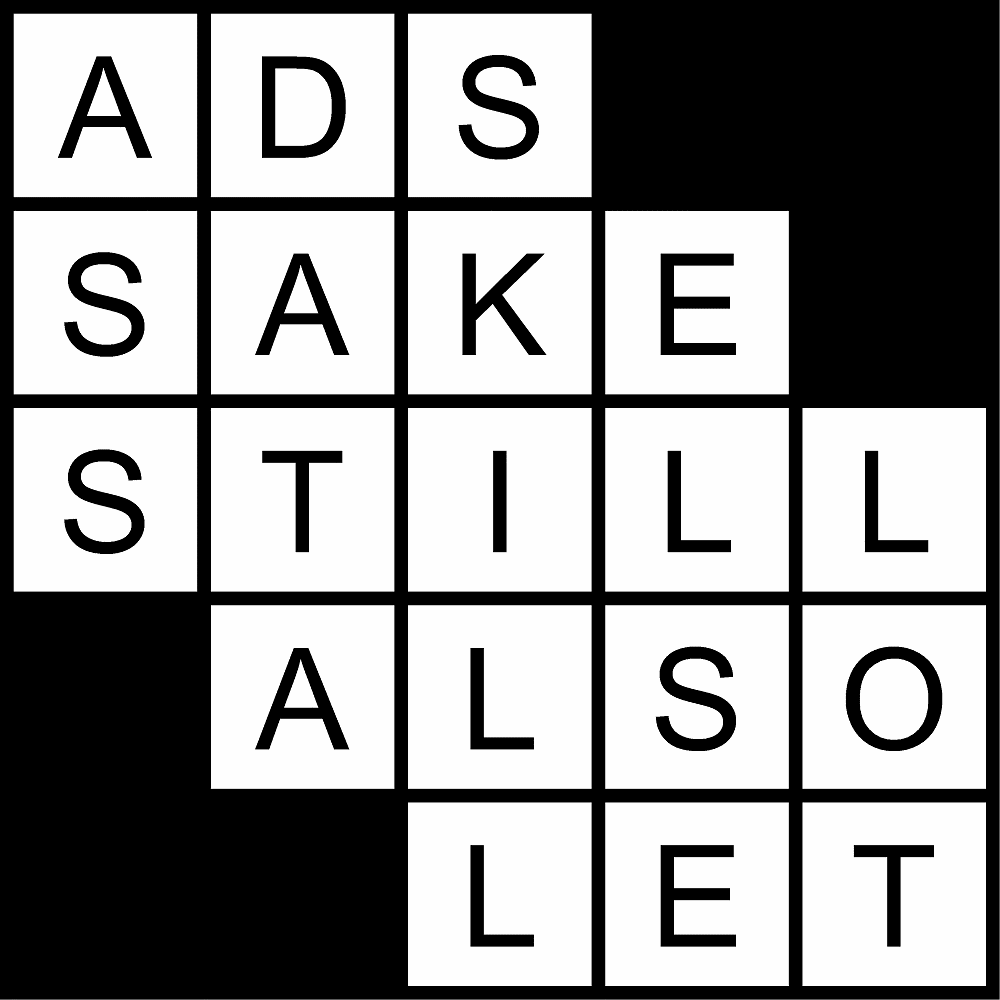

A simple 5x5 grid is not possible with the 5,000 most popular words in English. A black-and-white 5x5 grid is, though:

(I’m both surprised and kind of not surprised that ass is one of the most popular words in English, placing at 2,046. Sake, at 3,291, is the most uncommon here. I couldn’t say whether this is the most common-vocab 5x5 grid possible, but if not, it’s still in rare company—from the options my software gave me when constructing it, I’d estimate no more than 20 possibilities with this grid design, not counting across-down inversions.)