One feature of the Ubercross Abecedaria C that you probably noticed just by glancing at the grid is the pattern in the big “C” itself. It’s a lot…blacker, isn’t it?

In American-style grids, the rule is that every square should be part of two words, generally one running across and one down. Every single square, no exceptions.

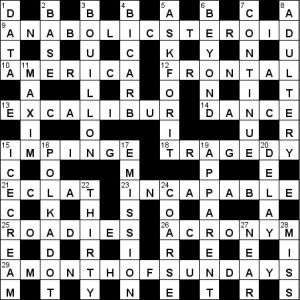

That’s a rule I follow in almost every part of the Ubercross Abecedaria, except inside the big C. In cryptics, though, the expectations are different…

Cryptic puzzles can (and usually do) have a number of uncrossed squares, which British fans call unchecked squares… or unches, for short.

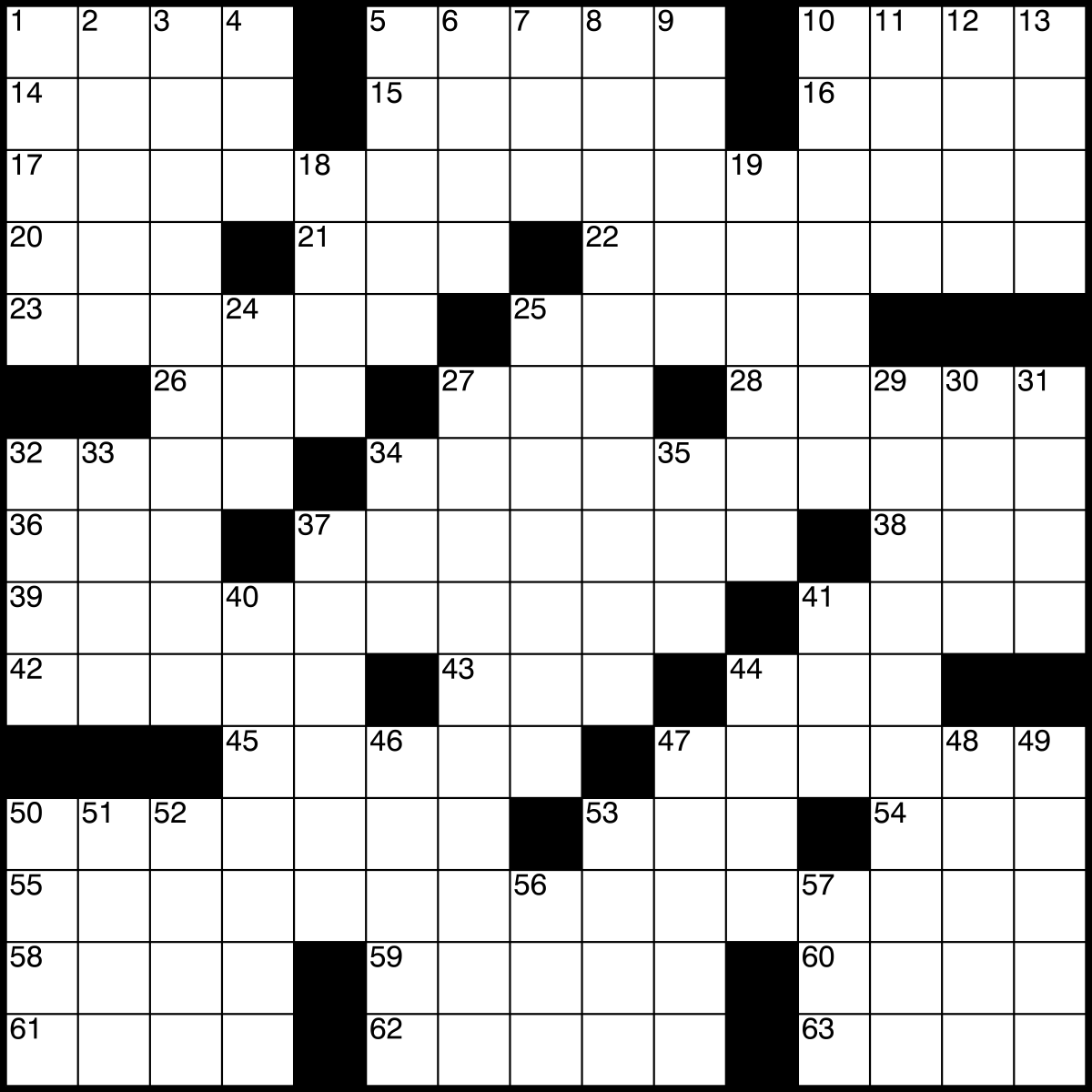

The exact number of unches permitted in cryptics is 50% of each word—usually—but when making the Ubercross Abecedaria C, I got confused by the rare exceptions. In the grid below, from The Independent’s Dave Gorman, two entries have more unches than crossed letters—EXCALIBUR and INCAPABLE.

But this is unusual in British cryptic puzzles, and almost never seen in American cryptics such as those in the NYT and the AVCX. Most editors would kick a grid like this to the curb before they even looked at the words inside it. The safe rule to follow is “50% unchecked or less” for every word.

Had I known this a few years ago, I would’ve made the unchecked side of the Ubercross Abecedaria C a bit tighter in places, to be truer to the cryptic tradition. But we forge on.

I’ve often viewed unches with a certain contempt. That contempt was reinforced when I used them in my first Ubercross and got called out for it as the rookie I was. But most of it comes from my experience as a solver. I had enough trouble with cryptics as it was! Unches just gave me more!

One of the strengths of the crossword puzzle is that you can solve it perfectly without perfect knowledge of its contents. If you don’t know who Addison Rae is (I didn’t, until I had to study TikTok a bit more), you can still get the answer to “TikToker Addison” by figuring out the words that cross that R, A, and E.

In an American puzzle, if that middle letter was unchecked, you’d be out of luck. Since cryptics have their own paired paths to victory (the “straight” part and the “cryptic” part), you’d instead get a clue like “Exciting era for Tiktoker Addison”…and if you got the R and E, you could probably deduce that her name was RAE, an anagram (“exciting”) for ERA.

Still, I can’t count how often I’ve frowned at a cryptic crossword—in my parents’ beach house, in an Oxford tea house, or in bed at home—and thought “Wouldn’t this be a smoother ride if the puzzlemaker could just give me more damn crossings?” So in the C puzzle, I did it both ways: cryptic-style inside the big C, American-style out of it.

It was educational. Cryptic fans argue their more open designs allow for more interesting vocabulary. And I could feel that freedom when it came time to fill that grid-within-a-grid. I didn’t have to do much backtracking or use any answers I didn’t just love. If the whole grid had been like that, I probably would have left out abbreviations like DECL. and partials like IN ART altogether.

I can see the distinction in terms of the differences between British and American culture, if I squint. Someone from the islands is more likely to be a reader and have a taste for longer words. We Americans, we like our spectacle, and if it takes more short, punchy words to get that tight grid interlock, that’s just fine with us.

I do like spectacle. But I also love the whole English language, from “humble, easy” entries like ERA and OREO to the showy, Scrabbly QUETZALCOATL and JAZZ QUARTET. (Cryptics rarely use three-letter stuff like RAE at all.) And I often enjoy how an American grid nudges me to an entry I’d never have thought of on my own.

The unch-ful grid design was a nice change of pace! But I won’t be making a habit of it. Grids A, B, D, E, and so on are unch-free.

As far as I'm aware, the unch rule in block cryptics is straightforward: minimum 50% of the letters in each entry must be checked. Take whatever leeway you need in an Ubercross, but the sample 15x15 grid here would be dinged by every editor.