With the Ubercross Abecedaria W, I got back to one of the primary kinds of wordplay, a kind that most of us learn in grade school: the homophone.

I’d passed over this species for the H-puzzle, of course, so saying “the H in this puzzle is for HOMOPHONES” was not an option. But I figured I could play on the phrase WORD OF MOUTH as a revealer…and also that this puzzle wouldn’t need much of a revealer in the end.

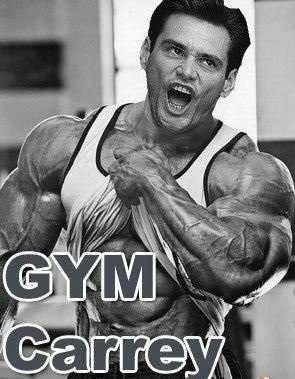

Once the solver saw entries like GYM CARRY and THAI BEAU in the grid, my little game would probably be clear enough: take a common multi-word phrase and replace each word with a homophone.

However, those specific entries—GYM CARRY (Jim Carrey) and THAI BEAU (tae bo) struck me as representing a problem. Most resources about homophones are woefully incomplete.

Go to an online resource about words that sound alike and you’ll probably find the old standbys. Two/to/too. Four/fore/for. Eight/ate. Maybe six/sics. But you won’t find proper names like Carrey/Carey/Carrie/carry, nor are you likely to find a “fossil word” like “tae,” which only exists in English when it’s accompanying “bo.”

Oh, and what about oronyms like “cell phone” and “self-own”? Yeah, you can just about forget trying to find those with any online resource. A few webpages will mention a couple examples like “I scream/ice cream,” but that’s about it.

In a way, it was liberating to get outside the old homophone dictionaries with some of my answers. But I think in terms of building systems, not just defying them. And if the system of finding homophones was this incomplete, I wasn’t content just to show it up. I wanted to find a better one.

It didn’t seem that difficult. All I’d need to do was find a way to turn every word or phrase into a written representation of its pronunciation. Like so:

/ɪt ˈdidənt siːm ðæt ˈdɪfəkʌlt/

/ɔːl aɪd niːd tuː duː wʌz faɪnd ə weɪ tuː tɜːrn ˈevriː wɜːrd ər freɪz ˈɪntuː ə ˈrɪtn ˌrepriːzenˈteɪʃən əv ɪts prəˌnʌnsiːˈeɪʃən/

/laɪk soʊ/

IPA notation like the above would be best, but almost any representation of sounds would do, as long as it was consistent. Because for my purposes, ease of reading didn’t matter nearly as much as sameness.

Once I got the pronunciations as a set of texts, it’d just be a matter of putting the texts into a spreadsheet, making a few adjustments (like removing the spaces and dashes for the oronyms), and then asking the spreadsheet to tell me which of the resulting cells held identical values.

Seemed easy, in theory. But when I tested “Jim Carrey and tae bo” on most online “translate-to-IPA” programs, I tended to get something like this:

/dʒɪm (Carrey) ænd (tae) boʊ/

Or even…

/dʒɪm Carrey ænd tae boʊ/

At least the version with parentheses admits there’s a problem here, but in either case, a resource that couldn’t read a simple name like “Carrey” was useless to me. It turns out that many translate-to-IPA programs were using the Carnegie Mellon pronuncing dictionary, figuring its 134,000 entries would suffice.

Still, computerized text-to-speech doesn’t stop dead when it reads a name like that. And because of how a computer “thinks,” any speech that it makes has to have some textual representation within its system. How hard could it be to find a resource that could handle “Jim Carrey” and “Carrie Bradshaw” and “Drew Carey”?

Tomorrow: As usual, way harder than I thought.