The Y in the Ubercross Abecedaria Y simply stands for “Why?” But that word covers a broader spectrum than you’d expect.

Why did the chicken cross the road? (To get to the other side.)

Why did the doodle chew up the other doodles in the sketchbook? (It was a labradoodle.)

A father and his boy were in an auto accident and rushed to the nearest hospital. The boy was found to need surgery. When he arrived at the operating room, the attending surgeon said, “I can’t operate on him! He’s my son!” No one questioned this, even though the father was in the next room. Why? (The surgeon was the boy’s mother.)

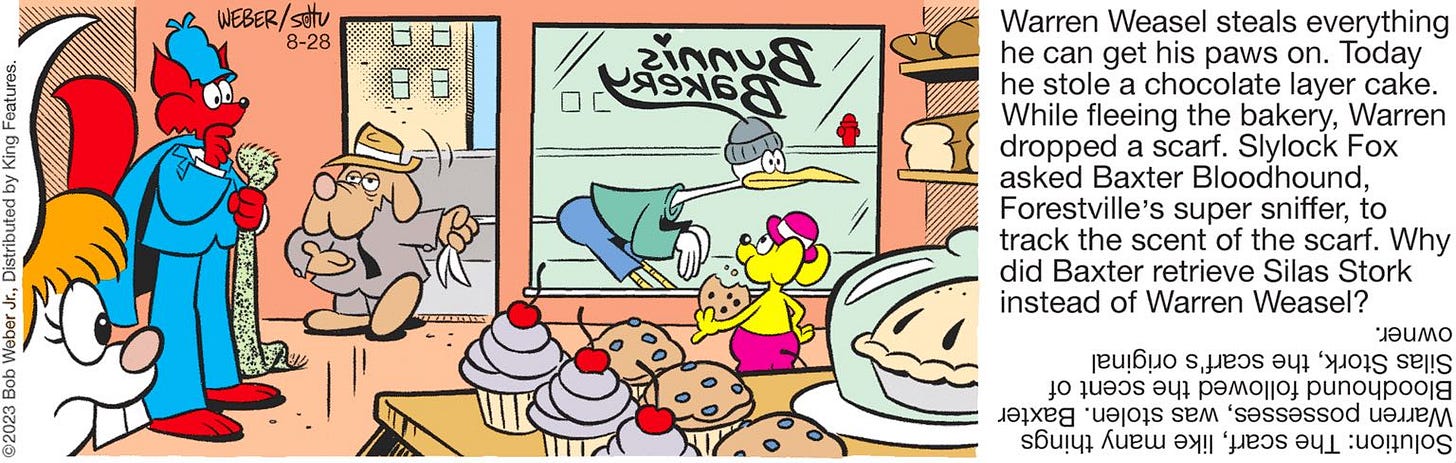

Warren Weasel steals everything he can get his paws on. Today, he stole a chocolate layer cake. While fleeing the bakery, Warren dropped a scarf. Detective Slylock Fox asked Baxter Bloodhound, Forestville’s super sniffer, to track the scent of the scarf. Why did Baxter retrieve Silas Stork instead of Warren Weasel?

The scarf, like many things Warren possesses, was stolen. Baxter Bloodhound followed the scent of Silas Stork, the scarf’s original owner.

The first two of these “Why” questions are riddles, the latter two are mysteries, maybe “quick mysteries” or “two-minute mysteries.” But I think the border between the types is a little fuzzy. Some mystery answers hinge on some chance remark the culprit makes that gives them away, and some riddles rely less on word games and more on a concrete understanding of the world.

All the mysteries described here are “plays-fair” mysteries, wherein an attentive reader has a chance of figuring out the answer. Every Slylock Fox tale gives the reader that chance, as do classic “kid detectives” like Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, and Encyclopedia Brown. But most Sherlock Holmes and CSI tales don’t. In a puzzle-making context, the audience has to solve it themselves—that’s the whole point.

“Why” isn’t the only question that riddles and mysteries offer. Some mysteries are whodunits, in which the reader has to deduce the culprit. Others are howdunits, in which the reader has to deduce the method, thus proving the culprit guilty.

Some riddles are the “what am I” variety, as in, “I am not in anything, yet I am the beginning of everything, and I will be at the end of time. What am I? (The letter e.)” All the other question words can inspire riddles as well:

A man shows you a photo and says, “Brothers and sisters I have none, but that man’s father is my father’s son.” Who is in the photo? (The speaker’s son.)

Where does today come before yesterday? (The dictionary.)

There are three apples and you take away two. How many apples do you have? (Two, the two you’ve taken.)

I am old enough to drive, yet I have only had five birthdays. When is my birthday? (February 29.)

In some riddle questions, the word “how” can just be swapped out with “why,” as in “How/why is a baseball like a cake?” (They both need a good batter.)

Still, I think there’s a fundamental “whyness” to puzzles like this. They’re about the root causes that define our world, the things that make it make sense and the things that make it absurd. And those are pieces of the great unsolved riddle—the riddle of being human in the universe.

That’s all I have to say about this one. Tomorrow: a version of Hamilton with a word lover’s twist…