Last time out, I asked “How hard could it be, making a giant anything-goes puzzle?” Harder than hard, as it turned out. But to explain why, I’ll take you through my process of making a simple one.

This is only my method. Others probably do things differently. Back in the 1980s, they would’ve had to, because I’m leaning on software that didn’t exist back then!

My first step is sometimes to decide on “seed entries,” stuff I’d really want to see in the final puzzle, which in turn would determine its shape. But for this one, I like the idea of going in “cold” and just letting circumstance inspire me.

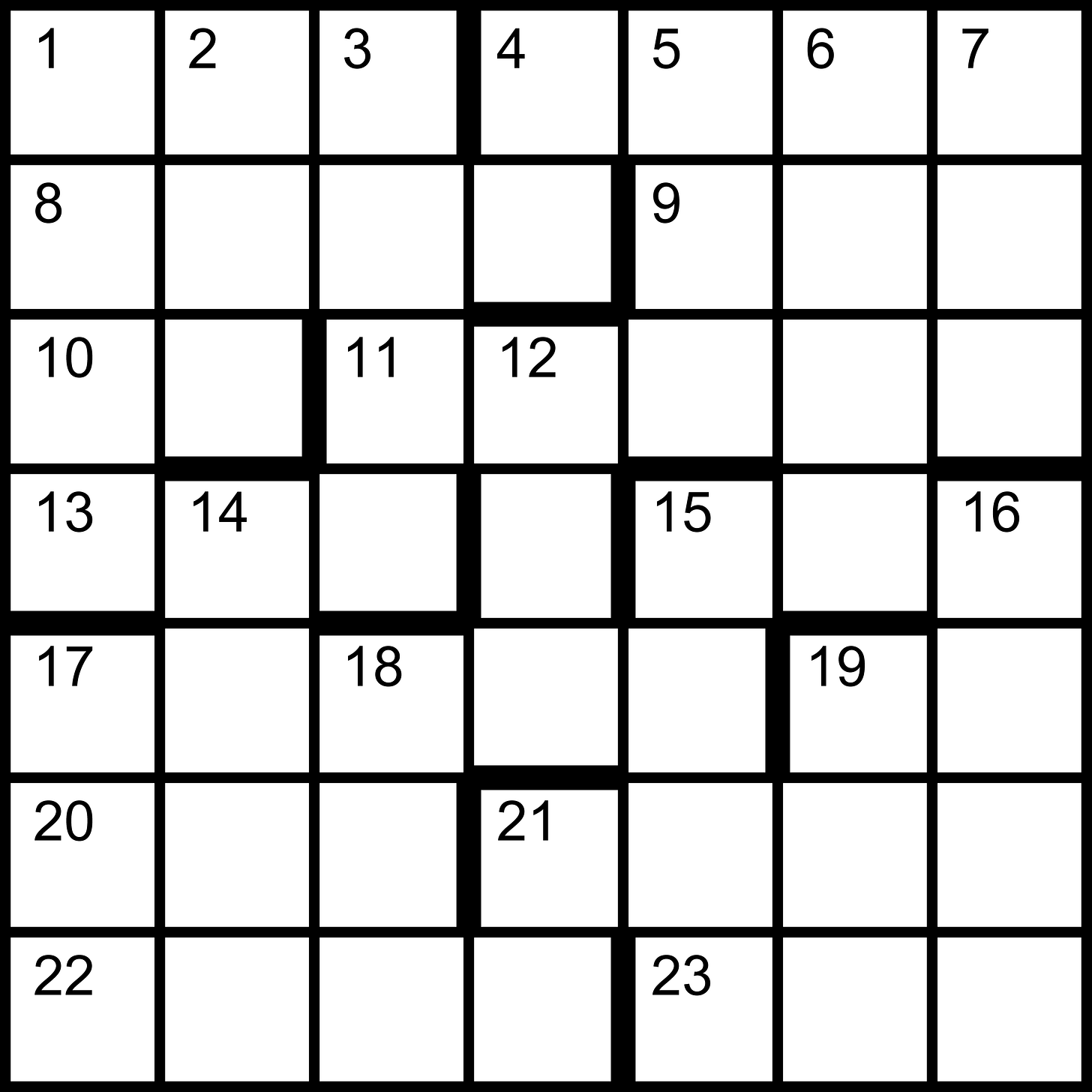

So instead, I’ll start by mapping out what I want the grid to look like. For this simple example, I’m using no black squares, but you can see I’ve inserted at least one bar into every row and every column, so the 14 words of a 7x7 grid have more than doubled to 30, counting the single square in the center going across.

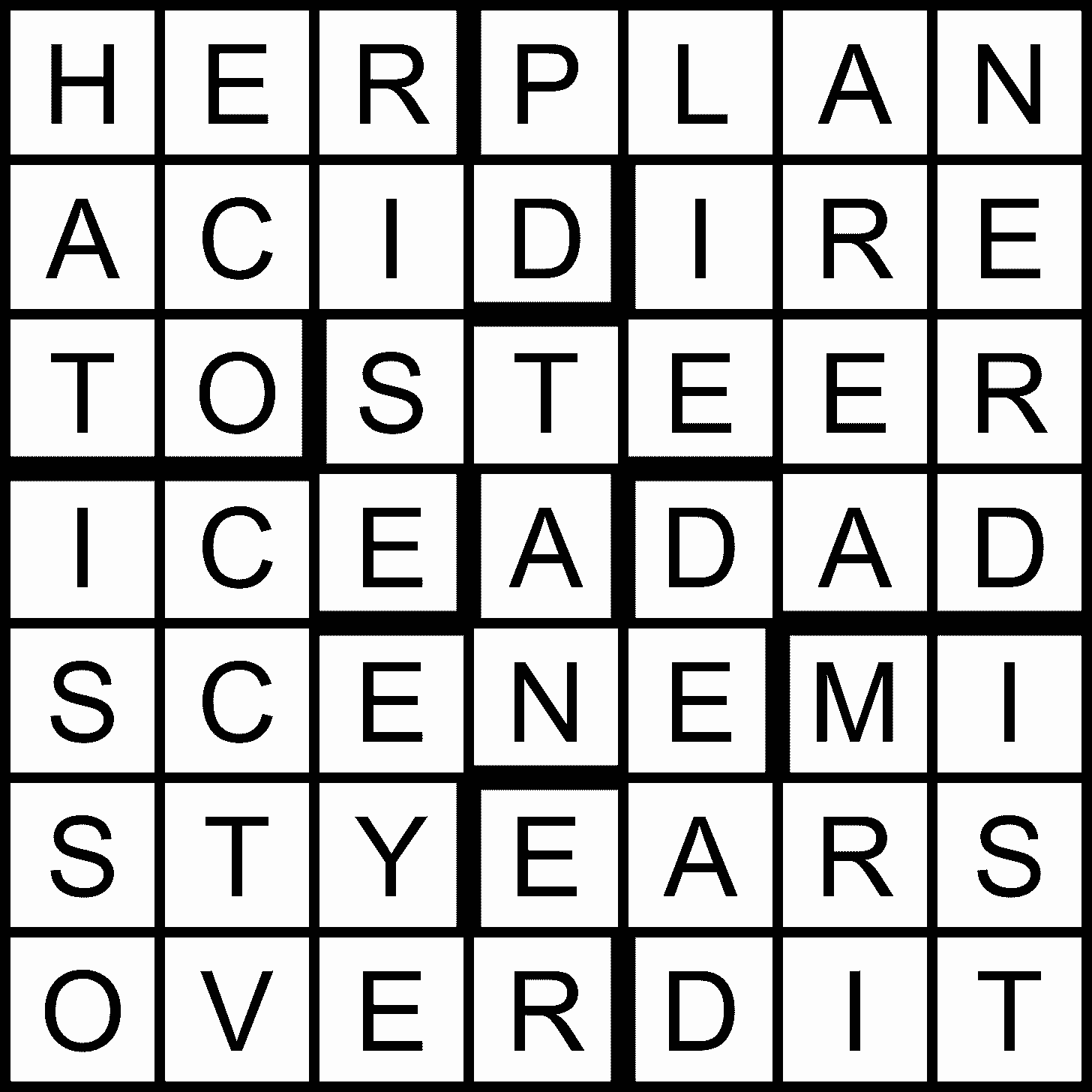

Next I fill in the words, one at a time. (I always pick “Manual word selection.”) Sometimes I hatch an idea for how they’ll relate to each other early on. For instance, one of the first words I fill in is SCENE with two empty spots to the right of it. I think about how often I’ve see ACT V and even SCENE II in a crossword, and I start thinking it’d be fun to write a clue where SCENE was followed by some more ridiculous Roman numeral.

Other times, I keep my options open until the end. I pick AREA as a modifier, with three empty spaces below it. As long as that three-letter word is a concrete noun, it could be almost anything and it’d work. AREA POT, AREA CAT, AREA WAX…they all could have clues starting with “Local” and some of the wry humor of The Onion’s “Area Man.”

Note that the bars in the first and last column have moved from where they were in the previous picture. Even though I start with a mapped grid, I’m willing to adjust it on the fly if it seems like I’ve hit on something that’ll work better.

Take out the bars, so I’m left with 14 answers after all…

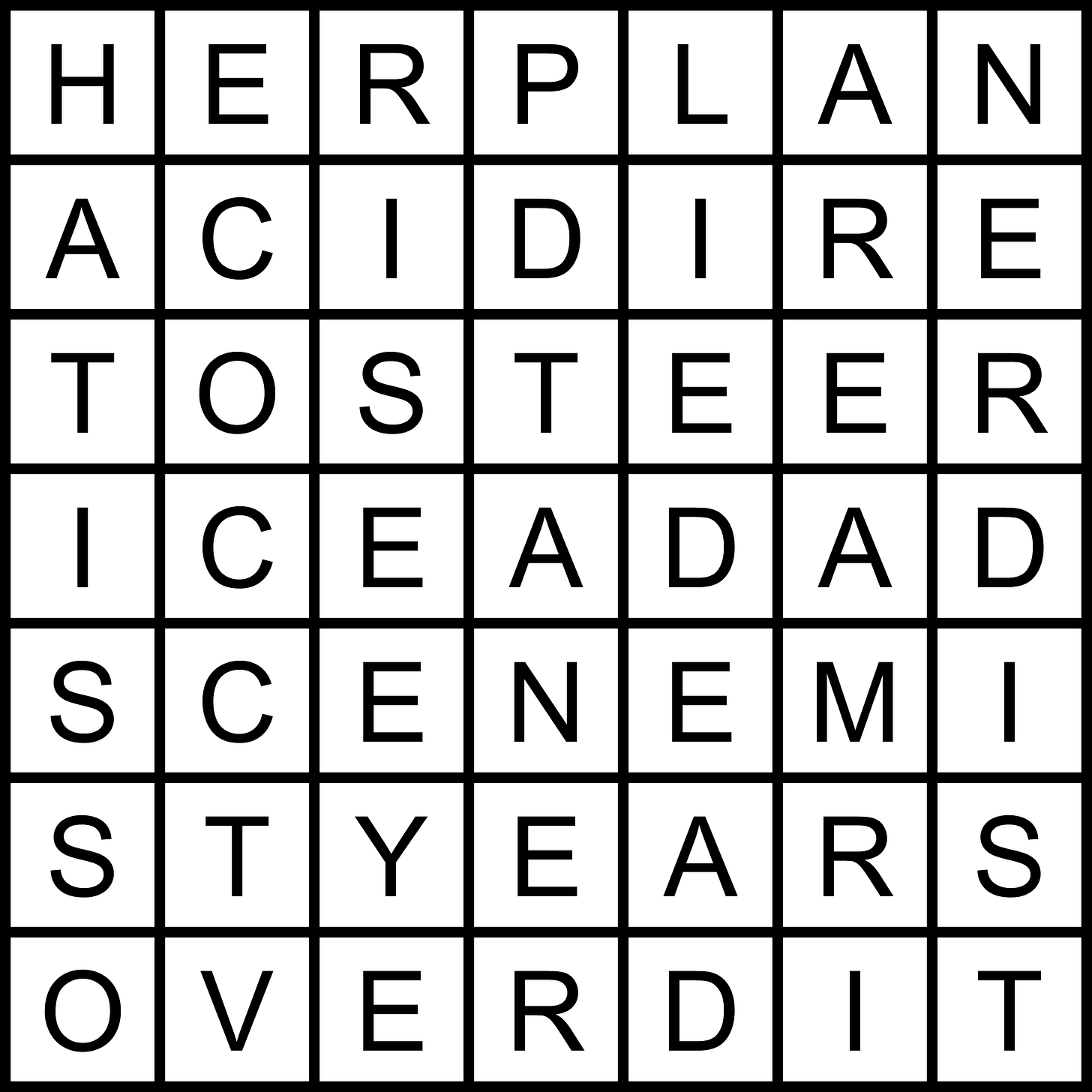

And then I start writing clues: “How she figured it’d go” (HER PLAN), “Corrosive anger” (ACID IRE), “Why cars have wheels inside of them, not just outside” (TO STEER), “Pop somebody’s pop, gangster-style” (ICE A DAD), “Last part of an overly literal stage production of 1,001 Arabian Nights” (SCENE MI)…

As an anything-goes…goes, this seems straightforward enough! It has a couple of mildly challenging down answers (HAT IS SO, PD TAN ER) and a couple that could have appeared in a regular crossword. LIE DEAD is a borderline-common phrase, and NERDIST is a podcast-and-entertainment-news brand. But there’s nothing here that a creative clue-writer couldn’t handle.

The “combine two normal answers” strategy isn’t the only one, either. You can strategically misspell words if clues are misspelled in the same way (POPCORNE for the clue “Noshe eaten while watching a filme”). You can try the occasional backwards spelling, vowelless answer, or other oddity.

And sometimes you can just use your imagination—I like BROBDINGNAG VS. LILLIPUT with “War between countries Gulliver discovered.” Maybe I’ll use that as a seed some other time.

So far, this is probably coming across like I thought it would: as a fun, low-pressure creative exercise, like an afternoon of finger-painting with the kids.

But tomorrow, we’ll see how it scales.

(To be concluded.)

THE ARABIAN NIGHT PLAY SCENE DESIGNATION -- MARVELOUS!!

The entire play would only be 15 minutres shorter than the movie OPPENHEIMER.