Steal This Technique! (Nested Book Titles)

Sorry for running late! The Excel file needed a tune-up, and I needed forty (or at least twenty) winks.

A few days ago, I outlined an effort to answer a simple question, “Which famous book titles appear, unbroken, inside other famous book titles?” You can download the resulting file right now, and reuse its formulas to find nested strings in a list of anything else. But I’ll talk through my process of creating it below. And then I’ll give you the juiciest data points.

As I said then, my first step was to assemble a list of book titles, using a set of five resources. I did so, though I had to modify my techniques a little on further investigation.

I integrated the lists from 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die, TheGreatestBooks.org, and Wikipedia’s list of bestsellers with minimal difficulty.

The full list of New York Times bestseller titles was too much for me to manage, so I pulled in the chart-toppers for each week in fiction since the list was founded in 1933, and the nonfiction chart-toppers beginning in 1968. Why such a late start with nonfiction? Because that’s what Wikipedia had available for easy copying. If I’d had a little more time, I would have folded in this list of NYT chart-toppers by Hawes Publications, but I reasoned that most well-known books from more than 50 years ago are likely to be either fiction or listed through other sources.

GoodReads data was likewise too tough for me to parse meaningfully, and it seemed like it was largely redundant with the other lists. So, in its place, I added the Publisher’s Weekly chart-toppers. Its bestseller list is even older than the NYT’s and nearly as respected.

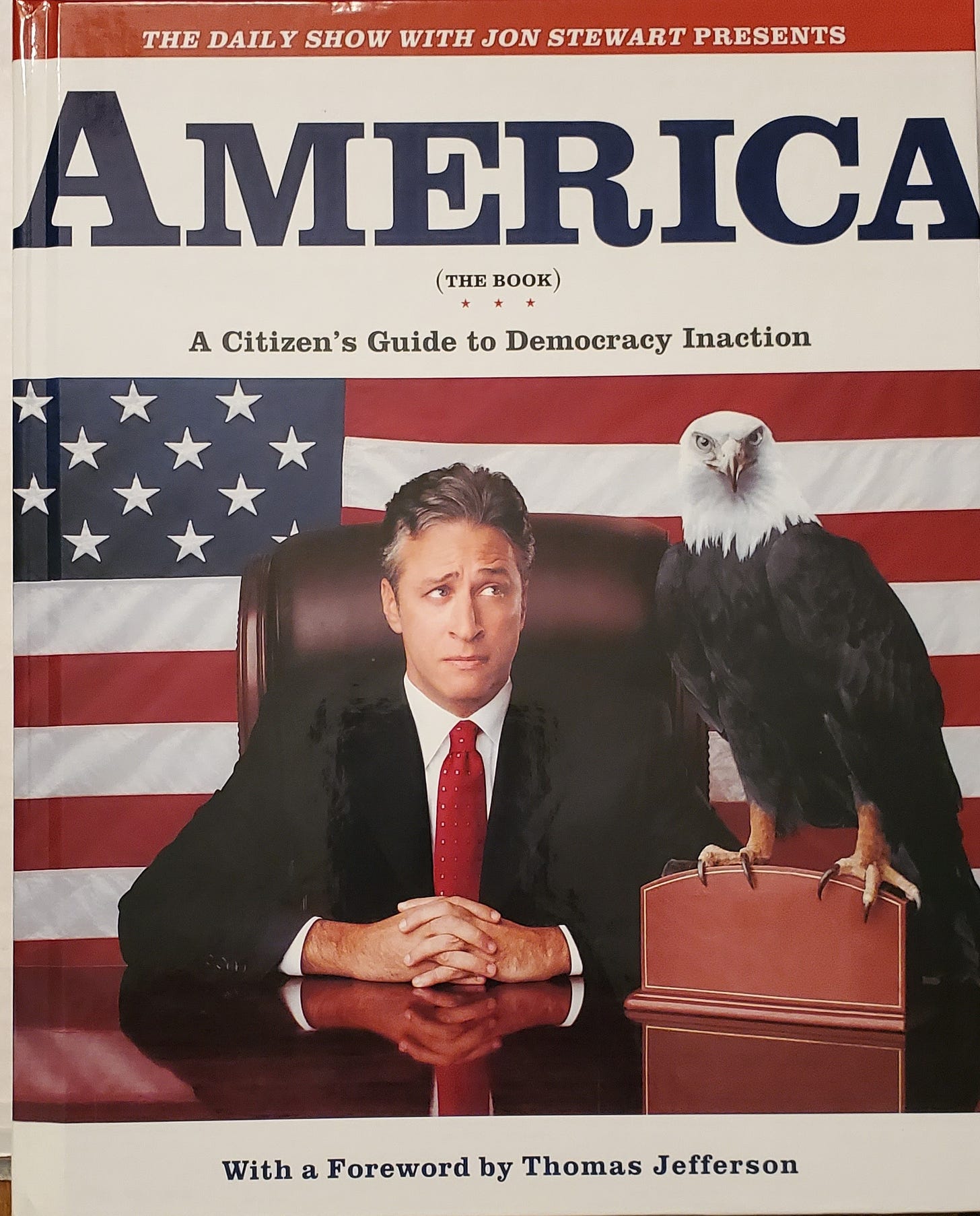

The hard part was combing out redundancies and making sure the listed titles were what people would actually call the book. In a few cases, subtitles or variant titles are an essential part of the main title. A good example is America: The Book by Jon Stewart and The Daily Show. The subtitle adds a dash of Stewart’s cheeky comedy and lets you know what to expect, much better than a single-word title like America could do. The shorter title would be a lot more useful to me (the “America” string shows up in 20 other books), but it wouldn’t be honest to use it.

In most cases, though, leaving that extra material in wouldn’t have been the best way to represent the book. Shakespeare’s most popular play is called Romeo and Juliet in most places, even if The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet was its full, original name. The cover of Stephen King’s It sometimes reads It: A Novel, but nobody calls it that.

Lots of times, translation glitches or other problems resulted in more than one version of a book’s title getting listed. I cut these wherever I found them, but a few have probably slipped by me. Charting dates and publication years were only available from some lists, but I kept that data, as they reminded me which list I’d pulled certain books from.

Results

I made searches case insensitive by copying all the titles, turning them to lowercase, and using an Excel function on the lowercase versions. However, I decided to keep spacing and punctuation: otherwise the dotted initial titles G., K., and V. would be a lot more prominent.

My final list of books, with all redundancies eliminated so far as I could see, was 6,497 entries. Of those titles, 531 appeared in at least one other title. Seventy-nine of the titles appeared at least ten times inside other titles. Here are the top 20:

There doesn’t seem to be much of a pattern of genre to the most “popular” entries: Me is a celebrity memoir, It is a horror novel (with a side order of hurray-for-the-good-guys adventure story), and We is a dystopian sci-fi novel that some cite as an influence on 1984. If is an inspirational poem, X is a mystery…so, yeah. Genre-wise, we’re all over the place.

Unsurprisingly, though, short titles tend to get repeated most often, and the list does favor pronouns. The top three entries here are Me, It, and We. One also places in the top six, and She is just outside the top twenty. More contemporary and popular-fiction books also seem highly placed, but that’s probably correlated with the short titles: there aren’t many older books or literary books that have really short, punchy names.

Lit is one of the top twenty…and every entry that contains Lit also, of course, contains It. One book title that contains Lit is Solitude, which is found inside 100 Years of Solitude; another is Lolita, found inside Reading Lolita in Tehran. These fourth-level nestings (a title inside a title inside a title inside a title) seem to be as complex a Russian doll as we can build.

Note that our “Times Featured” column counts appearances of the title string in the list, not number of books in which the string appears. For most entries, this doesn’t make much of a difference, but the two single-letter titles, Z and X, owe multiple appearances to entries like Sizzling Sixteen by Janet Evanovich and Encyclicals of Pope John XXIII.

The longest title found inside another title, discounting direct sequels and likely duplications, is Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica, found in Bertrand Russell’s The Principia Mathematica. But those titles feel like minor variations of each other.

The longest strings otherwise tend to be names of famous historical figures like Frederick Douglass, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Theodore Roosevelt. All of these are titles of biographies, and they hide within other biographies (of Roosevelt), collected writings (of Emerson), or both (The Autobiography of Frederick Douglass).

And finally, a few new favorites I found with this method that no one’s mentioned yet:

The Really Good Stuff

Travels by Marco Polo inside Gulliver’s Travels (Jonathan Swift) and Travels with Charley (John Steinbeck)

X by Sue Grafton in Sex by Madonna in Joy of Sex by Alex Comfort.

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man shows up in H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man and Mychal Denzel Smith’s Invisible Man, Got The Whole World Watching.

Things by Georges Perec (yep, him again!) in Needful Things by Stephen King and Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe.

Twilight by Stephenie Meyer in Twilight Sleep by Edith Wharton.

Fear by Bob Woodward in Fear and Trembling by Søren Kierkegaard and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson.

And to bring this all full circle? This started when I noticed The Road hiding in On The Road. But it turns out The Road is hiding inside six other titles…most famously, Bill Gates’s The Road Ahead and Charles Kuralt’s A Life on the Road. And Kuralt’s book is hiding On The Road, too!

The process of finding film titles embedded in longer film titles and, similarly, finding book titles embedded in longer book titles can be extended to other groups of things. Let’s call this “Things Embedded In Similar Things”, or TEISTs, or maybe even ThEISTs. Here are some from other groups:

US states (these are easy!):

Kansas in Arkansas

Virginia in West Virginia

Countries:

Oman in Romania

Mali in Somalia

Niger in Nigeria

Sudan in South Sudan

Elements:

Erbium in terbium in ytterbium

Tin in astatine and platinum

Tin in actinium in protactinium