A couple of months back, I discussed Babylonian acrostic poems as part of the prehistory of crosswords. There have been many translations of these poems, but none of them have been interested in preserving their acrostic nature in English.

The longest and most interesting of the poems is the Babylonian Theodicy. Most others are simple hymns of praise to gods or kings, but the Theodicy, as its name suggests, is a dialogue about divinity. While one of the speakers, the “friend,” takes the role of a reassuring religionist (trust in the gods, justice will win out in the end), the other, the “sufferer,” expresses anxieties quite relevant to twenty-first-century life.

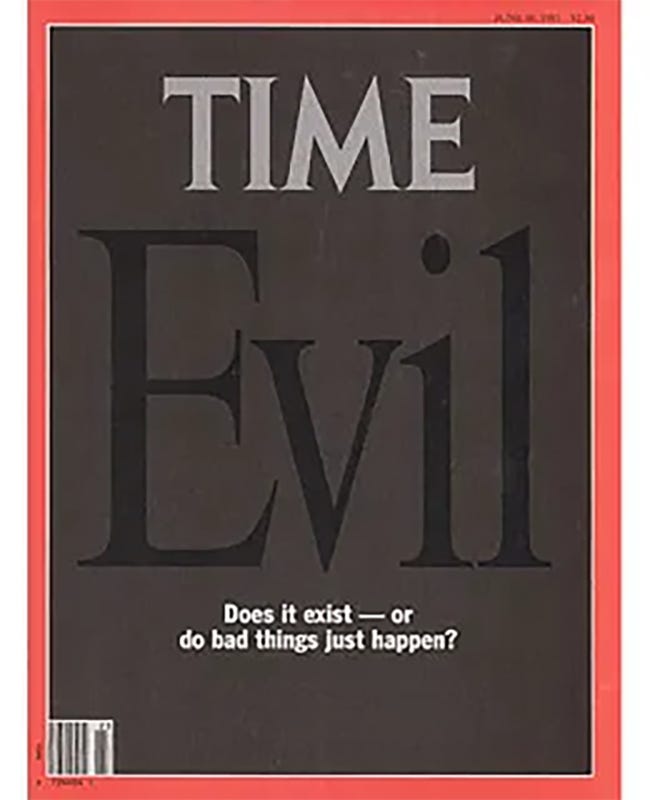

Although the Theodicy wanders a bit, it’s a dissection of the Problem of Evil: “If God (or divinity) is omnipotent and good, then why do bad things happen?”

Here’s the first strophe (stanza) as translated by Takayoshi Oshima. Oshima’s translation is the most extensive and best we have so far:

Strophe I-Sufferer

1 Wise one, [...] come, [let] me tell you,

2 I go[t (it)], companion, [let] me recount to you [(my) pl]ight.

3 [...] [...].. in your stomach (i.e. the seat of emotions),

4 let [me], who am greatly in distress, praise you.

5 Where is the wise person who equals you?

6 What learned man can compare with you?

7 Where is the sage (to) whom can I recount my grief?

8 I am finished (i.e. exhausted). Anguish has come straight to (i.e. attacked) me.

9 When I was still a young child, fate struck (my) begetter (i.e. my father died);

10 the Land-of-No-Return took away (lit.: killed) the womb who bore me (i.e. my real mother).

11 My father and my mother left me (behind) with no guardian.

Note that lines 1 and 3 are incomplete and 2 and 4 are filled in by educated guesswork. Whole strophes are missing in the current translation, which presents another challenge, but this first part gives us more than enough to get the gist.

In the original version, each line in this eleven-line strophe begins with the same sign. The poem has twenty-seven such strophes, each likewise alliterated. Read in order, those beginning signs spell out a disclaimer that names the author:

I, Saggil-Kīnam-Ubbib, the incantation priest, am adorant of the god and the king.

“Opinions expressed by my ‘sufferer’ are not necessarily my own. I’m a loyal believer and a true patriot, sire! You’ve got no reason to execute your old friend Saggy, no sir!”

To render this as a modern acrostic, we’ve got to start by deciding how to render this key. Since modern acrostics are graphic (letter-based), a good starting point seems to be getting it down to 27 letters. Here are a few tries I made at that:

SAGGIL-KINAM-UBBIB LOVES RULERS

LOVE GOD, KING—SAGGIL-KINAM-UBBIB

SAGGIL-KINAM-UBBIB: YAY GOD ‘N’ KING!

I, THE PRIEST, LOVE THE GOD AND KING.

Excising Saggil-Kīnam-Ubbib’s name from his work feels wrong, like cropping out an artist’s signature on purpose—but his name takes up sixteen of the twenty-seven letters allowed, which doesn’t leave much room to render the rest of the key. Reluctantly, I find the fourth option the best, since it reads clearest without spacing or punctuation: ITHEPRIESTLOVETHEGODANDKING.

As a side benefit, most of its letters are easy to work with. Here’s a version of that first strophe again, adjusted so its lines all start with I (passing over line 3 for now as too incomplete to adjust):

1 Insightful one, come, let me tell you,

2 I have a tale, companion, let me recount to you my plight.

3 […] in your gut,

4 If you permit, I in my great suffering would praise you.

5 In what place is the wise person who equals you?

6 Indeed, what learned man can compare with you?

7 Is the sage here to whom can I recount my grief?

8 I am finished. Anguish has attacked me.

9 I was still a young child when fate struck my father,

10 Incursion from the Land-of-No-Return took the womb who bore me.

11 I had no guardian; my father and my mother had left me.

Next time out, we’ll up the challenge level! I’ve already mentioned the syllable-based acrostic…

WONDERFUL POST. Thank you for your curiosity & research skill.