The Guiding Tropes of the Modern Super-Team

What if you made super-characters based on each of THESE, and teamed THEM up?

I’ve talked about the super-team’s beginnings, internal conflicts, and strange “mainstream” variant. Since the 1980s, it’s been tough to track super-teams’ development, mostly because there have been so damn many of them (good and evil).

I mean, pick a topic. Natural disasters? There’s a supervillain team for that, the Masters of Disaster. Microscopic universes? There’s a superhero team for that, the Micronauts. “Space aliens among us” paranoia? Snakes? Playing cards? Lucky charms? Celebrations of Hinduism and Islam? Football? There’s a super-team for that (Skrull Kill Krew, Serpent Society, Royal Flush Gang, Luck League, Sanjay’s Super Team, The 99, Kickers, Inc.).

(Talking animals? Don’t get me started.) Some such groups are now inactive, but any could return tomorrow.

But though the field is messy, a few themes keep recurring.

Major-League Impostor Syndrome

The Justice League and Avengers are often called “the world’s greatest superheroes.” Some A-listers—Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman, Captain America, Thor—live up to that hype. Others, while respectable, seem elevated above their peers more by tradition and nostalgia than inherent greatness (“Aquaman and Hawkeye are superhero icons!” “…Why?” “Well, they’ve…always been around, and…” “What defines iconicity?” “No further questions!”).

However, writers like to keep things fresh, and “iconic” characters are sometimes unavailable. (Spider-Man and Wolverine often have other commitments.) Like the JLI, many teams have wrestled with public perception (and private insecurity) that they’re not the “real” Avengers, X-Men, or Justice League. But if they form their own group, they still get those comparisons! Stop judging them, will you, fans? You’re so unfair!

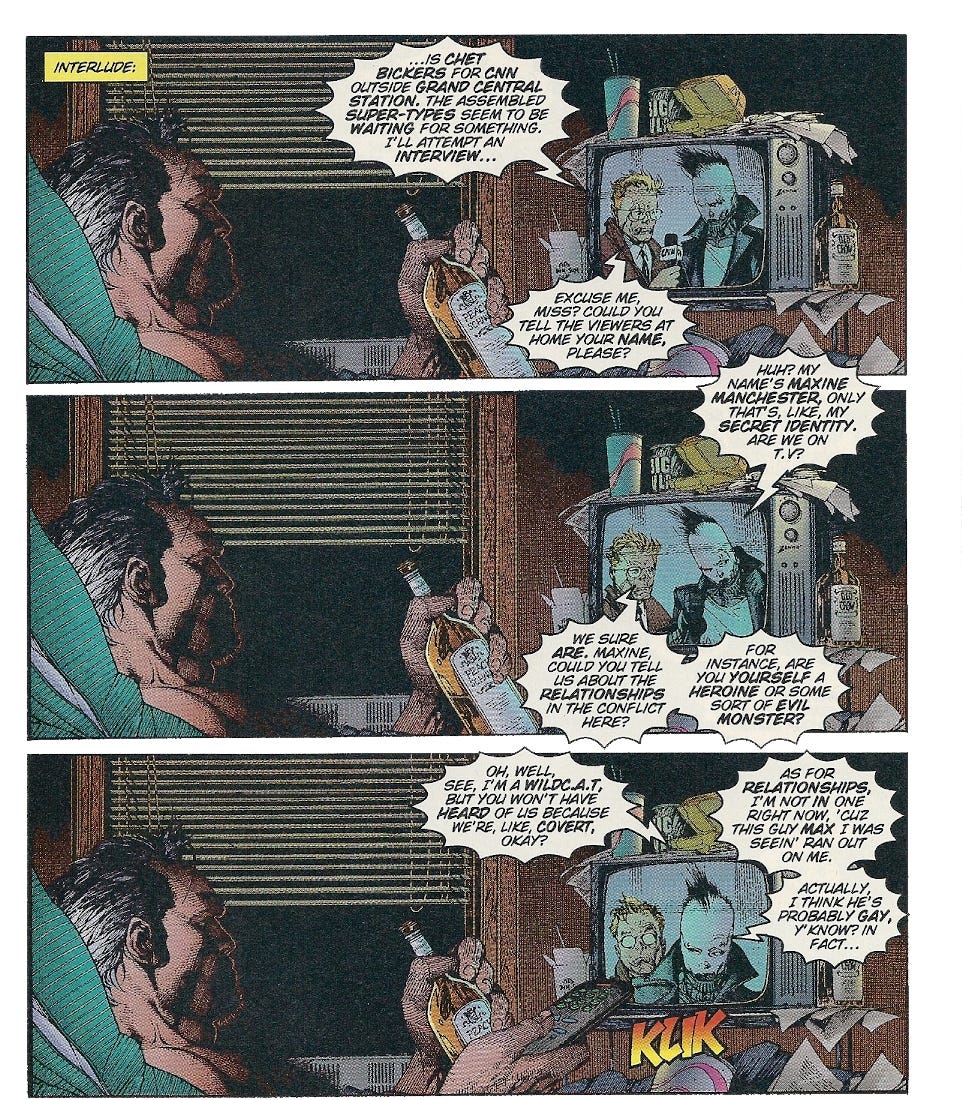

“Covert” Action Teams

The Suicide Squad has a secret. They’re supervillains but serve US interests to shave years off their sentences—often through CIA-style black ops. The WildC.A.T.s were heroes but also secret warriors against alien insurrectionists. The Thunderbolts were first villains posing as heroes, then heroes misperceived as villains. The Runaways were runaways because their parents were villains. The Illuminati? The Secret Warriors? The Secret Six? Shhh, they’re secret.

Superhero (and villain) action tends to be loud and public, so these groups have trouble keeping their true purposes hidden. Though sometimes, even they don’t know those purposes (WildC.A.T.s #31)…

Coming of Age

The happiest ending is the promise of a better tomorrow. Although Batman and Spider-Man never quite age out of the field, the next generation of heroes always seems just around the corner. Sky High, My Hero Academia, and sometimes X-Men depict hero schools. Other series involve young people finding, helping, and training each other.

In an antisocial century, with gatherings of friends at an all-time low, a bunch of young’uns hanging out all the time feels almost as aspirational as puberty giving you super-strength.

Spotlight-Chasers

Not every hero group is hero-ing for good reasons. Some are just proving they should be in therapy. Others seek fame—which rarely works out for anyone. Best-case scenario is they’ll discover altruism along the way. Worst case? Their own deaths (see X-Statix, below) or civilian casualties and a superhero civil war (see Civil War, the comic. The Umbrella Academy mixes those best and worst cases.)

Social Movements

“Fighting for justice” is nice in the abstract, but some groups have more concrete goals. The Champions combine youth-group energy with idealist activism. The real heroes of The Boys take a desperate stance against corporate and political consolidation of power. The X-Men have stood for minority rights since the 1960s.

Mutants are a fictional minority, which might seem like a dodge. And sometimes it is. But some minorities fighting for their rights today went unrecognized in the 1960s, and the mutant metaphor has expanded to include them.

MCU Envy

Say, did you know Marvel Studios rolled characters from its movies together into a single mega-franchise? The “Marvel Cinematic Universe”? Revolved around the Avengers? Ring a bell?

It made a little money.

In response, film studios keep organizing super-teams (Justice League, Madame Web), trying to recapture that “Avengers” magic.

But nobody tries as hard as Marvel itself. It’s rolled its Netflix TV heroes into the Defenders, set up a new generation of Avengers, prepped a Thunderbolts* film for 2025, and most ridiculously, teamed up batches of alternate-universe characters from its What If TV series whose only common ground was appearing in What If. (And “not wanting the multiverse to die,” I guess, which seems like a low bar.)

The movie Avengers were a mismatched bunch too, and overcoming their differences—or failing to—was key to their story. That story hit the cinema like lightning. But lightning rarely strikes twice, even if you bring in Storm or call your team “the Thunderbolts.”

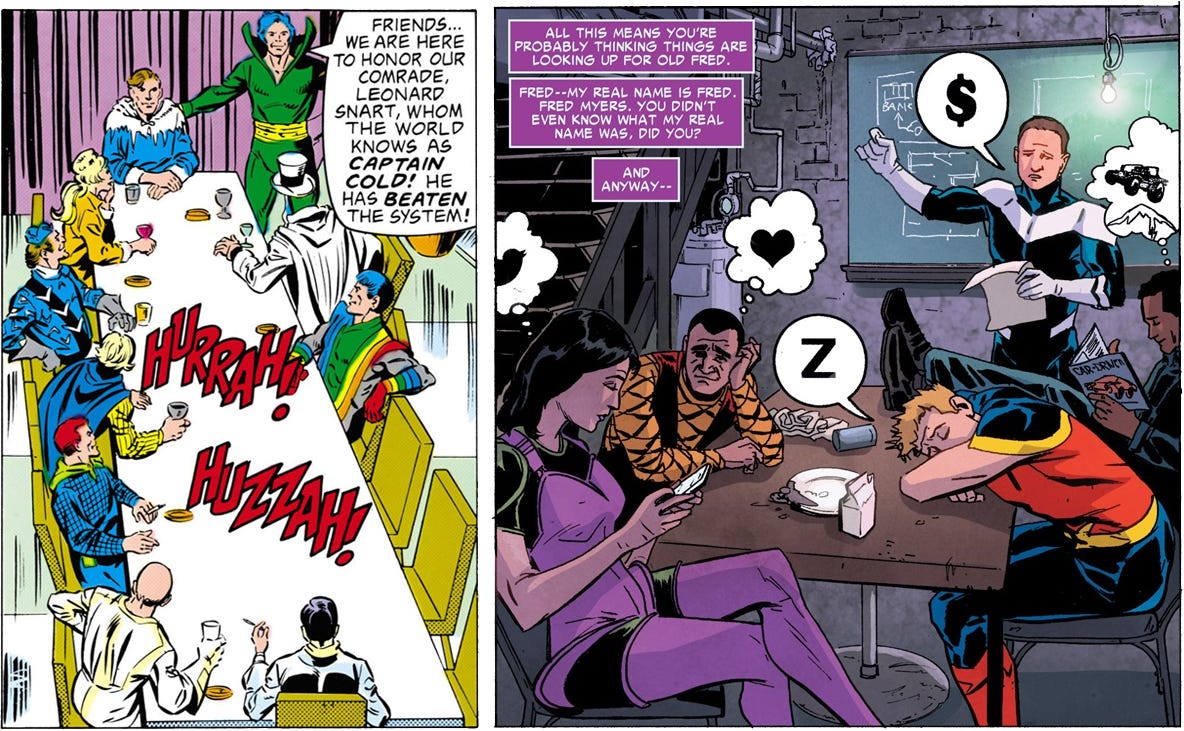

Villain Villages

Villain teams squabble more than hero teams since many prominent villains are obvious sociopaths. The original Sinister Six could’ve probably killed Spider-Man for good by now, if not for their (fully justified!) mutual mistrust.

Yet many modern stories revolve around a “found family” of villains (the Hulk’s U-Foes, the Flash’s Rogues Gallery, the Injustice League). Sympathetic bad guys can be fun. Even if they are doomed never to defeat their enemies in the end…there’s a comfort in being failures together (Flash v2 #19, Superior Foes of Spider Man #1).

Next: The Neil Gaiman thing (sigh). And next Sunday: the hero who could’ve replaced Superman.

One tragedy of our time is that too many people sit back and wait for superheroes to

save them when ordinary acts of kindness and intelligent decision making would better

serve them and the interests of their communities. Teams of Superheroes? Who or what

created super villains in the first place? We all did.