Most articles about wordplay imply that it’s an impossible field to organize. Play is just whatever goofy shit you come up with, right?

Not so, really. Play has structure and rules that we all quietly agree upon. And if you spend enough time with various forms of wordplay, you start to see structure there too—fundamental things in common, categories, subcategories.

Broadly speaking, there are three categories of wordplay: visual, phonetic, and semantic. I’ll cover “visual” today and move to the other two types tomorrow.

The visual type further subdivides into alphabetic, image-specific, and matrix types. Alphabetic types of wordplay involve the letters that make up the words, and nothing else really matters but their meaning.

Alphabetic types involve some of the best-known wordplays, especially to people who seek out wordplay. Within that heading are yet more subheadings, including anagrams, letter-patterns, letter requirements, and alchemies.

An anagram is any word or phrase that has the same letters as another, in a different order. A semordnilap is a kind of anagram where the letters are exactly reversed, “war” for “raw,” “gateman” for “nametag.”

Here’s the first wrinkle in the system: most people would put semordnilaps next to palindromes. But they really don’t behave the same at all—a semordnilap is a relation of two words or strings, while a palindrome is a single word or string that has an unusual quality.

Of the letter-patterns, palindromes are the best-known: their letters are symmetrical, as in “redivider.” There’s also repeaters (“can-can,” “beriberi”) and neckouts (“legal age,” “teammate”). For isograms, the pattern is no pattern: all letters are unique, which is unremarkable in a four-letter word but gets more impressive in words or strings of ten or above, like “uncopyrightable.” Overlapping all of these are cryptograms, words and phrases that share an unusual pattern, like “alfalfa” and “entente.” (There are also “natural ambigrams”: we’ll come back to those.)

Letter requirements divide into letterbanks (which allow the use of some letters and forbid others) and letter musts (which require the use of some letters and may have other constraints). The definition of the letterbank overlaps with that of the lipogram, but there’s a difference in connotation. For the most part, lipograms are longer works allowing most of the alphabet to be used, whereas letterbanks are shorter items allowing less than half of the alphabet to be used. Often the letterbank’s “bank” is a single isogrammic word or phrase, like “lens” for “senselessness.”

Letterbank/lipogram variants include monovocalics, which use only one vowel, though they resolve the y question in different ways. Variations on the letter must, though, include supervocalics and euryvocalics, which include all vowels once and only once—supers use just AEIOU, and eurys include the “y.”

Letter musts include nested words, nested anagrams, and kangaroo words (where one word or string must contain another according to various rules) and pangrams (where all twenty-six letters have to be in there somewhere).

Alchemies include exercises like add-a-letter, subtract-a-letter, and change-a-letter. You can change “a” to “any-example-of-a” here, and/or change “letter” to “string.”

The image-specific kind of wordplay depends on specific visual presentation. This includes tricks of typography like kinetic typography, logo design, and most ambigrams. A few words show “natural” ambigram qualities in most typefaces, like “bid” or “NOON,” but most need to be designed to work as they should.

The natural ambigrams are better classed with the letter-patterns. That’s another oddity of the system—that it separates some ambigrams from others—but it’s ultimately a logical one.

Image-specific wordplay also includes pictographs like emoji 🤪, photos, or icons as substitutes for words. Tricks with sign language might also qualify.

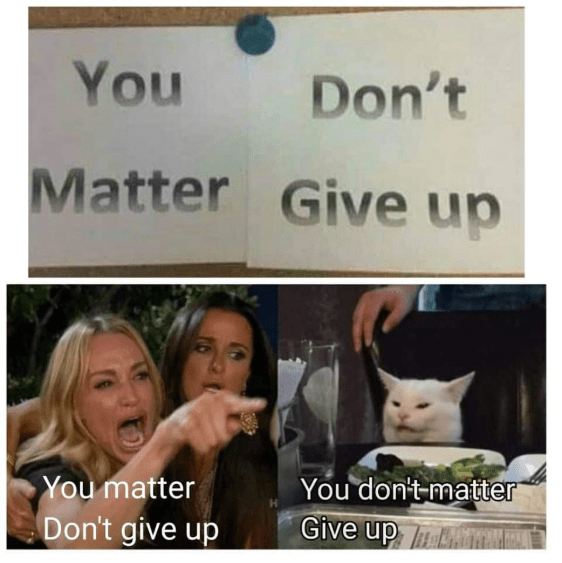

Matrix types are in between the alphabetic and image-specific types, in that they don’t need a specific image or typeface but do require a certain arrangement of letters on the page. They include crossword grids, but also word searches, crossword variants like the snake charmer, and other tricks of visual arrangement (like the meme below).

This matters, so I won’t give up. More tomorrow!