A lipogram is a piece of writing that works off an alphabet with pre-set, declared limits. Examples include novels that exclude the letter e and poems that use only the letters in a famous person’s name. A word lipogram (as mentioned in Anil, “Word Lipogram Sentences: Commonest Words; Pronouns,” The Journal of Wordplay #1) is a piece of writing that works off a limited vocabulary.

Like regular lipograms, word lipograms need to work off pre-set, declared limits to really count. Many ordinary sentences do not contain all twenty-six letters, and no piece of writing includes every word in existence. Some children’s books are said to have “limited vocabulary,” but those limits are usually vague. They’re more based on intuition than on any restrictions you could nail down.

Here are a few more specific constraints. Today’s installment deals with some declared word lists. More tomorrow!

Seussian: The Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham by Dr. Seuss. You’ve probably encountered at least one of these books, but you may not know that they were written under outside constraints. CITH was written using 236 of the 250 words recommended to Seuss by his publisher (with repetitions allowed, of course). Hearing this, a friend bet Seuss $50 that he couldn’t write a book using just 50 words. Green Eggs and Ham won Seuss that bet.

Children’s authors have, of course, used even more constrained vocabularies than this, since some kids’ books now have no words at all. Seuss, for his part, got less constrained after Green Eggs and Ham, and his later books are a lot more willing to just make words up. But it is impressive how dense Green Eggs and Ham is able to make its fifty words feel. Even in an adult reading…it’s a hearty breakfast.

Basic English: The Rights of Man by H.G. Wells and C.K. Ogden. Ogden was one of the great thinkers on linguistics and spent the back half of his life promoting Basic English, a system of 850 English words chosen to do the work of 20,000. Ogden wasn’t a promoter of dumbing things down. Rather, he wanted complex ideas to have a better chance of being understood, and not only by children but also by non-native speakers who had limited experience with English.

Time hasn’t been kind to Basic English. Controversial in its own day, it hasn’t been updated since 1927, which leaves the basic-english.org website unable to describe itself. Most people who say “BASIC ENGLISH” today mean lowercase-b basic, not Ogden’s system. While he was alive, though, Ogden found support from sci-fi authors like Robert Heinlein and H.G. Wells. Wells authorized some Basic English versions of his own works: you can read this one here.

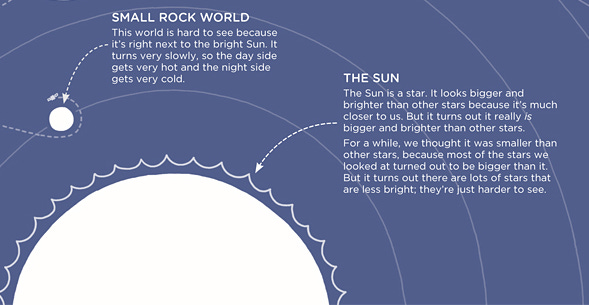

The thousand: Thing Explainer by Randall Munroe. Last time I mentioned Munroe in this space, I hinted I’d have a reason to do so again, and here it is. Munroe’s exercise here is to describe everyday science using a limited vocabulary. That vocabulary? The 1,000 most common English words, as he determined for himself through a variety of sources. Mercury, for instance, is renamed “Small Rock World.”

Often, Thing Explainer’s explanations are startlingly clear or yield new and interesting insights. Occasionally, they do get labored—but that’s part of the tongue-in-cheek humor of the book and can make it more entertaining, not less.

A quick footnote: the “words” of Basic English and Thing Explainer are root words. “Explainer” is not on either list, but “explain” is, and “explainer,” “explaining,” “explains,” and “explained” are usable as part of its “family.” Probably “explanation/s,” too. Explanations isn’t as fun a title as Thing Explainer, though.