This continues the list of word-lipogram styles that I started yesterday. The fourth entry here uses lists of words derived from other works; the next two exclude certain parts of speech.

Ophelian: let me tell you by Paul Griffiths. Griffiths tells the story of Shakespeare’s Ophelia using only the 481 words that are found in her dialogue in the original Hamlet. She’s given the internal life that she mostly lacks in Shakespeare, and a growing sense of the limitations of her existence that allows her to escape the play’s fate.

Other examples of this kind of “derived vocabulary” include “Their words, for you,” an exercise by Oulipian writer Harry Mathews. It uses the words found in just forty-six well-known proverbs.

Also, here’s a protest poem using official words about the Witness Protection Program to subvert it. Here’s some poetry using words found in selected writings of Virginia Woolf.

Non-verb-al: The Train from Nowhere by Michael Thaler. Thaler’s work may be unique: a full-length novel without verbs. It’s largely an impressionistic view of a train ride, beginning like this: What luck! A vacant seat, almost, in that compartment. A provisional stop, why not? So, my new address in this nowhere train: car 12, 3rd compartment from the front. Once again, why not?

Unfortunately, as far as I can tell, it’s not very good. Critics have mentioned a lack of action, which seems to be inevitable in a verb-less book, but the excerpts I could uncover also seemed downright hateful of the speaker’s fellow passengers, if not humanity in general.

Now, I can understand feeling a little hate for humanity during a long, cramped train ride. But that doesn’t make it an enriching experience to read about. Thaler, you’re already testing the reader’s patience with this verbless, impressionistic style, and now you’re going to insult them too? That’s really the road you want to go down?

Also, Thaler seems more than a little disingenuous when he says (italics mine): “The verb is like a weed in a field of flowers. You have to get rid of it to allow the flowers to grow and flourish. Take away the verbs and the language speaks for itself.” Does it, though? Try reading that passage without the verbs and see how far you get.

I’m not just bringing this up to pick on Thaler, though. I do appreciate how he’s proven a verbless book is possible. Perhaps someone else can take that lesson and create one that’s more of a gift to the world.

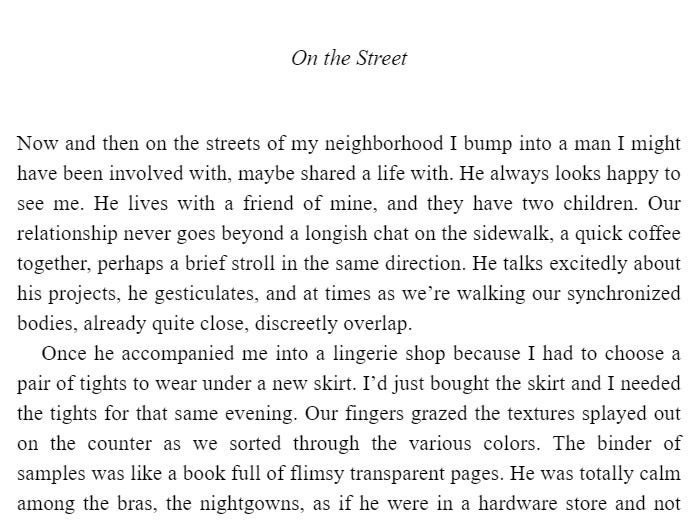

“Nameless”: Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri. Lahiri’s work, published in English just two years ago, is a book without place names or character names. (More generally, it does allow a few proper nouns, such as the names of months.) Lahiri’s unnamed narrator walks through an unnamed city. She’s lost her sense of purpose and her enthusiasm for her work as a professor, and her one close relationship, with her recently widowed mother, never measures up to what she wants it to be.

Lahiri’s language is poetic and powerful. Context clues hint that the narrator is living in Italy, as Lahiri herself did, but in a broader sense, it doesn’t matter. Each chapter heading is simple, nonspecific scene-setting—“In the waiting room,” “In my head,” “In August”—and even as we share some of the narrator’s dislocation, we get to know her city as she sees it. It’s her only companion, and it’s the one that she’ll have to abandon if she’s to grow.

I’ve read other works that are similarly “nameless,” but most are graphic novels. Can’t think of any others just now. At least not by name.

Concluded tomorrow…