In a prior pair of entries on this Substack which became a Journal entry, I started laying out a wordplay schema, a set of nested categories for the whole field. I did this in hopes that it would make wordplay easier to create, study, and otherwise think about. It’s helped me organize some of my thoughts, at least!

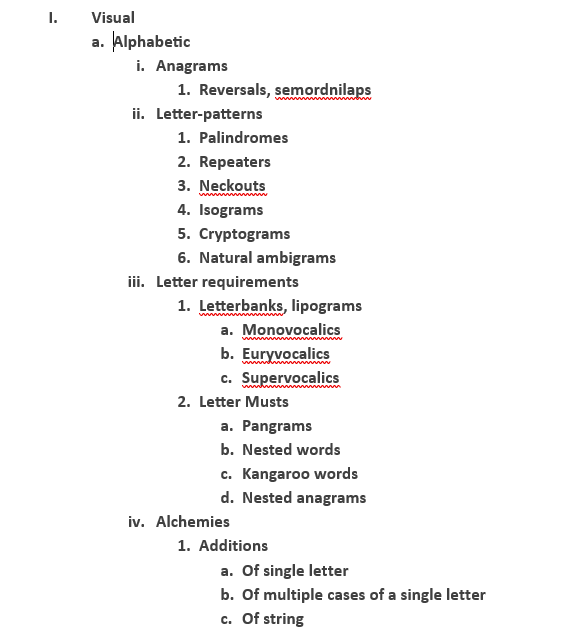

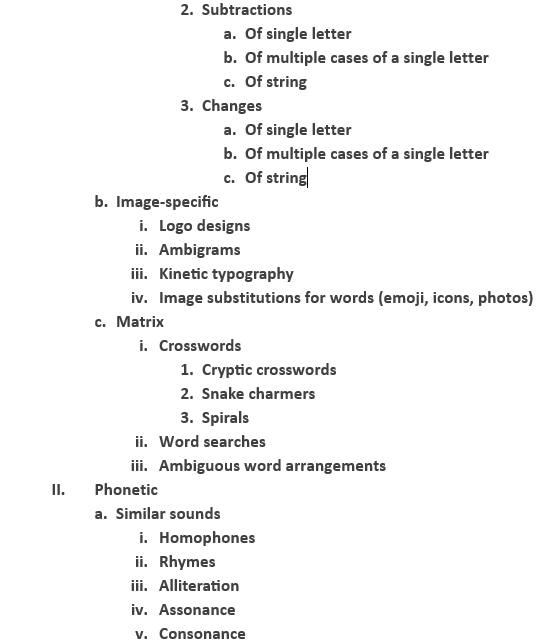

Below is the outline of wordplay types as laid out in the prior work. It’s some quick-and-dirty cut-and-pastes from a Microsoft Word document, as indicated by the red underlines:

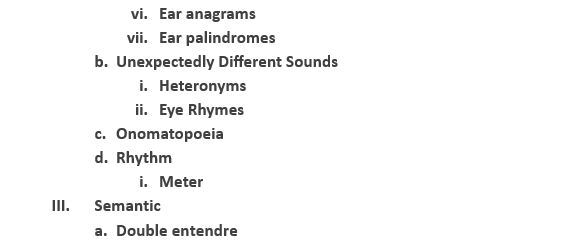

Not a lot going on in the semantic section, I know! The new schema, coming soon to The Journal of Wordplay #3, addresses that lack and other issues. Checking Wikipedia’s forms of word play page showed me whole sections I was missing (as below).

Missing entries were not the only issue to deal with. I gnashed my teeth about the fact that the schema had no spot for what we consider the simplest form of wordplay—puns. Or rather, too many spots for them.

Puns can be visual, relying on heteronyms (or homographs) like so: “The would-be conqueror ended up ‘ruling’ nothing but wastelands—he had gotten his just deserts.” Some are phonetic, homophonic: “Look! It’s the werewolf wizard, Hairy Potter!” Or they can play off shades of meaning in words that sound and look the same: “You call me a MAD scientist? Why, I’m FURIOUS!” Near misses can also be puns: “To animated gas salesman Hank Hill, his work is both sacred and propane.” Is that a visual or phonetic pun? Hard to say.

In other words, puns cannot be confined to one part of this schema: they run all the way through it. After reflection, though, that feels correct to me. “Pun” is too general a term to work with the kind of classification we’re going for here.

When does playful language become just…language? I had to ask myself this when getting into zeugma and grammatical syllepsis. What do those terms mean? In general, they mean one phrase or word with more than one interaction in a sentence.

These can be straightforward, as in “He sipped, then drank, then drained the drink,” where “he” and “drink” interact with three verbs. Or they can be playful, as in “I held my nose and temper,” where “I held” interacts with two nouns, with one use of “held” staying literal and the other entering a figure of speech.

There are overlapping definitions of the terms, but the playful uses of this concept are thought of as zeugma. So it got placed in the updated schema, whereas grammatical syllepsis did not. Other “edge cases” like this also called for thought.

And then there were different kinds of playing, different contexts of play. There are differences between how puzzlers play, how poets play, and how fiction writers play. Puzzle answers need more unwritten rules than poetry, because an answer has to be guessable and gettable. Poetic language is freer to be expressive, but only a fiction writer can create a brand-new language like Klingon.

A post like this can only scratch the surface of the issues involved! The Journal piece includes some of the above text but adds further thoughts, and where the earlier schema had rougly 60 categories, the new one has over 200. Thanks to Janice to some crucial feedback, and all of you for encouraging this pursuit!

Tomorrow: More Schrödinger clues!